Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826) was born at Shadwell Plantation in Albemarle county, Virginia. He died at Monticello just a few hours before John Adams on the fiftieth anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. His tombstone indicates what he wanted to be remembered for: the Declaration of Independence, the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom, and the founding of the University of Virginia. His father died in 1757 and left him nearly 3,000 acres of land. In 1772, Jefferson married Martha Wayles Skelton who died in 1782. They had six children in their ten year marriage, but only two lived to maturity. Jefferson probably fathered six children with Sally Hemmings, one of over 600 slaves he owned.

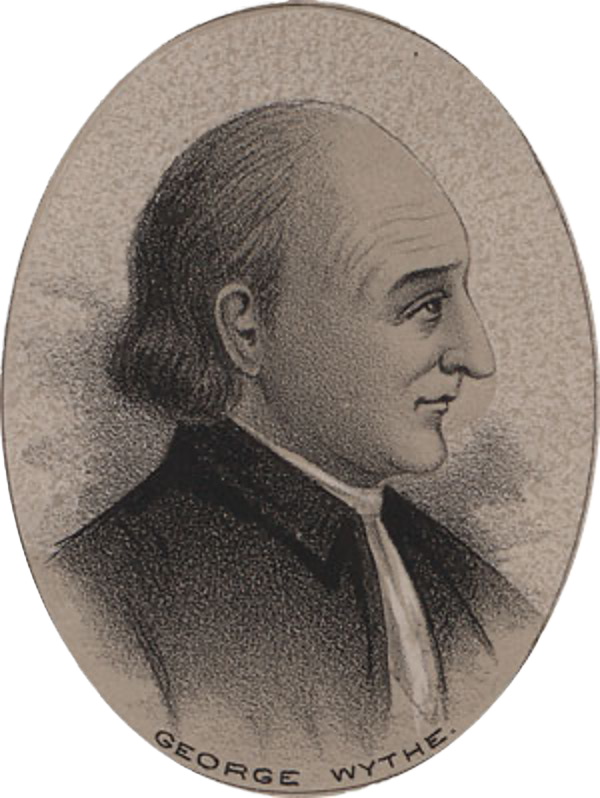

He was tutored by the Reverend James Maury in the classical tradition studying Latin, Greek, and French at age 9. He graduated from William and Mary College in Williamsburg at age 19, studied Law under George Wythe, the first professor of law in America who later would sign the Declaration in 1776. Jefferson was admitted to the Bar in 1767.

Jefferson attended the House of Burgesses as a student in 1765 when he witnessed Patrick Henry’s opposition to the Stamp Act. He was elected to the House of Burgesses in 1769 and served continuously until 1775. Jefferson’s involvement in revolutionary politics began and matured here in Williamsburg. Although never a vocal member, his written drafts and committee work made him an invaluable member of the House. In 1774, Jefferson drafted a resolution that called for a “Day of Fasting and Prayer” in response to the passage of the Intolerable Acts that formed the basis of his pamphlet A Summary View of the Rights of British America that denounced British control of the colonies. It was widely read throughout the colonies and even in England where it was promoted by Edmund Burke.

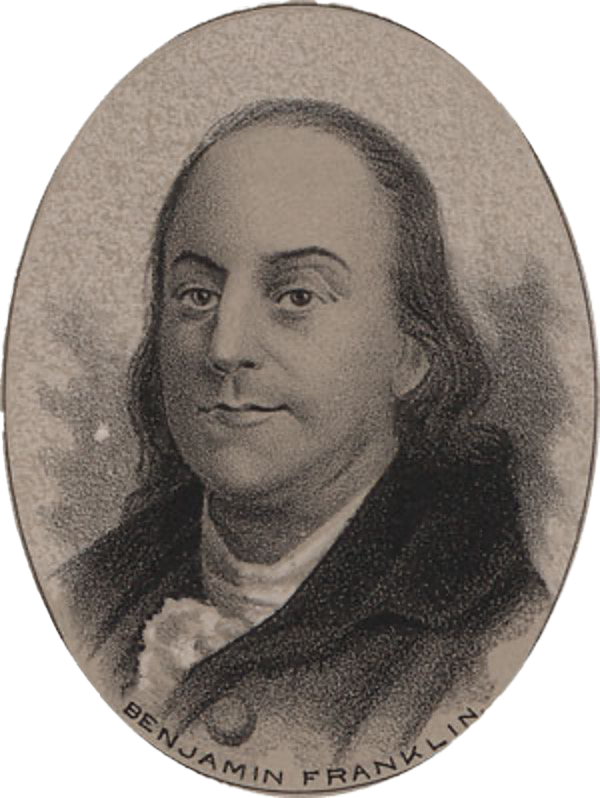

In 1775, Jefferson was elected as a replacement delegate to the First Continental Congress, but most of his suggestions because of their strong opposition to British rule. Things were different in the Second Continental Congress; the case for revolution had become stronger than the case for reconciliation. Jefferson was chosen to a five member committee that included John Adams, Ben Franklin, Roger Sherman, and Robert Livingston, to draft the Declaration of Independence. He was chosen by the committee in turn to write the draft. The document, that included minor modifications from Adams and Franklin, was presented to the Congress on June 28. The Congress debated the draft on July 1 and excised a passage critical of the King, and an anti-slavery clause that according to Jefferson offended the South Carolina and Georgia delegations. The Declaration was adopted on July 4 and most of the delegates signed on August 2.

Jefferson returned to his home in Virginia in September where he served in the House of Delegates from 1776 to 1779. He drafted the Virginia Statute of Religious Liberty in 1777 that declared that all men “shall be free to profess… their opinions in matters of religion.” This proposal was not passed by the Virginia legislature until 1786. In June 1779, he succeeded Patrick Henry as Governor of Virginia. The southern colonies were under heavy attack from British forces and Jefferson proved to be an ineffective war time Governor. He declined re-election after his first term and was succeeded by General Thomas Nelson, Jr. who also signed. The Declaration of. Independence.

In 1781 he retired to Monticello, the estate he inherited, to write and attend to his ailing wife. Martha died in September 1782. Retirement, however, proved to be temporary. He was elected to the Confederation Congress in 1783 where he wrote the Land Ordinance that ceded Virginia’s Northwest Territories and included the Jefferson Proviso” that banned slavery in the territories. In 1784 Jefferson went to France with Franklin and Adams to negotiate commercial treaties. He succeeded Franklin as Minister to France in 1785 and served in that position until 1789.

He returned to America in 1789, and was appointed Secretary of State by President George Washington. Jefferson, however, disagreed with Alexander Hamilton on the constitutionality of the Bank and with other Federalists on the direction of the country was taking under strong national leadership. He resigned from the cabinet in 1793 and, with James Madison, formed the opposition Democratic Republican party. Jefferson ran for president in 1796 but lost to John Adams. Under the rules of the Electoral College, Jefferson became vice president to a person whom he no longer respected. And even as vice president, he was bold enough to support the Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions in opposition to the Alien and Sedition Acts.

Jefferson again ran for the presidency in 1801 and won. In victory, he graciously remarked in his Inaugural Address that “we are all Republicans, we are all Federalists.” Witness the peaceful transition of power in America, “the world’s best hope.” In fact, the election was contentious. Jefferson beat Aaron Burr in the House of Representatives on the 36th ballot with the assistance of Alexander Hamilton.

Jefferson retired, finally, to Monticello in 1809. In 1815, he sold his own personal library to Congress to help launch the Library of Congress. With his long-time friend and ally James Madison, he helped establish the University of Virginia in 1819. Jefferson died on July 4, hours before Adams, as the nation celebrated the fiftieth anniversary of the Declaration of Independence.