The Six Stages of Ratification: Stage III

Winter in New England: Postpone and Compromise

Massachusetts February 6, 1788

New Hampshire (postpones) February 24, 1788

Introduction

Despite overwhelming success in-doors, the Madisonians were well aware of the difficulties that lay ahead. Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Virginia, and New York were still to come and they knew that North Carolina and Rhode Island weren’t going to sign. In addition, the Antifederalists had been effective in the out-of-door pamphlet war. Agrippa from Massachusetts published 11 Letters “to the people,” and 5 essays “to the Massachusetts Convention” by February 5. Similarly, Brutus from New York published 11 of his 16 essays, Cato from New York published all of his 7 essays, Centinel from Pennsylvania published 14 of his 18 letters, and Federal Farmer from Virginia published all of his 18 letters between October 1787 and the start of the Massachusetts ratifying convention. The Antifederalists had lost the fall in-door debate but they were mounting a formidable out-of-doors campaign that would spill over into the subsequent in-doors debates. I think that it is more than coincidental that it’s right around January 1788 when the 36 opinion pieces written by Publius between October and December were bundled up and put in book form and called The Federalist.

In other words, the difficult journey still lies ahead because 1) in-doors, six states are in doubt and 2) out-of-doors, there is a flood of Antifederalist essays that were starting to have their impact on the electorate and on the election of delegates. The early optimism of The Federalist that maybe we don’t need to do much more than write 20 essays defending the Constitution from Antifederalist criticism had faded by early 1788. In Federalist 37, Madison says, “We really need to have a more copious investigation of all of this.” And it’s at that time that Madison invites readers to take a look at the miracle that occurred in Philadelphia during the 1787 Constitutional Convention. Madison realized that ratification had entered a new and crucial phase.

Massachusetts

The Massachusetts Ratifying Convention met in Boston from January 9, 1788 to February 5, 1788 to discuss “the adoption of the federal Constitution.” 370 delegates had been elected on October 25, 1787, and when the final vote was taken on February 3, 355 registered their vote. One of the leading authorities on the Massachusetts Convention, John J. Fox, deems the entire experience to have been undemocratic: “If the people of the commonwealth had been allowed to vote directly, they would have determined against ratification; so would a majority of delegates if they had been asked to cast their votes in the early days of the convention.” He saw the Federalists as “cunning.” Similarly, Jackson Turner Main noted that “The Federalists employed unethical means.”

In attendance from the Philadelphia Convention were Caleb Strong, Rufus King, and Nathaniel Gorham. Fisher Ames, James Bowdoin, Francis Dana, and Theophilus Parsons joined them in defending and urging the ratification of the Constitution. The fourth Philadelphia Convention delegate, Elbridge Gerry who declined to sign the Constitution on September 17, 1787 was not in attendance. Within the first week of the Convention, however, “a motion was made and passed, that the Hon. Elbridge Gerry be requested to take a seat in the Convention, to answer any questions of fact, from time to time, that the Convention may ask, respecting the passing of the Constitution.” Gerry agreed to the invitation the very next day. But Gerry never made it to the floor of the convention and after January 19, he disappeared completely from view. Absent Gerry, people with less prestige and experience led the opposition.

Over the first two weeks, the delegates discussed Article I, Sections 2 and 4. On Monday, January 21, the start of the third week, they turned their attention to Article I, Section 8, namely, the Powers of Congress clause and concluded on Saturday, January 26 with a discussion of Section 9. During the first four days of the fourth week—Monday, January 28 to Thursday, January 31—the delegates covered the remainder of the Constitution although there is no record of any discussion of Article IV! Some of the most interesting discussion takes place over the last week. There was an attempt by previously quiet Samuel Adams and John Hancock (he didn’t attend until January 30 because of gout and had not announced his stance on the Constitution) to accommodate the opposition by suggesting that amendment proposals be annexed to the ratification.

No one was really sure where John Hancock stood. I put him down as entering with a no vote. Hancock, although his signature is large on the Declaration of Independence, was viewed with suspicion by both sides. Either way, with that close of an anticipated vote, something had to give. If it were 300 to 55, nobody would have had to budge. And, fortunately, Hancock was absent for the first three weeks of the conversation because of gout.

The low road explanation is that a bunch of Federalists went up to John Hancock and said something like this, “John, you know that George Washington is going to be President. The question is, who’s going to be Vice President? John Adams is a possibility. But how about John Hancock? Does that name sound good? We like that ticket: Washington-Hancock.” And the story goes that Hancock said, “What’s in it for you?” The deal was that in exchange for the Vice-Presidency, Hancock wouldn’t run an opponent against the Federalists in the next gubernatorial election. That’s the low road explanation. Rufus King‘s correspondence with Madison gives some credence to this low road explanation: “Hancock‘s character is not free from caprice.” Madison, in turn wrote to Washington: “the decision of Massachusetts either way will involve the result in this State.”

The high road explanation is that responsible leaders from both parties, including Adams and Hancock, convened and said, “Look, we’ve been at this now for nearly a month. We’re not making any progress whatsoever. The country is in crisis and if Massachusetts doesn’t sign, then we’re down the tubes. Is there some way we can come to some common ground on this?” And the common ground was that Massachusetts would ratify now with an expectation that in the First Congress amendments would be proposed to alter the Constitution. This is known as the Massachusetts Compromise. And enough people bought into it because Hancock bought into it, that it swayed enough delegates to ensure ratification. So the high ground is the sense of crisis, the sense of duty, the sense of Hamilton‘s remark in Federalist 85 that states would be better off signing quickly and working within the system, and that sense that Massachusetts had a responsibility to step up and take the lead.

But in the name of what authority can a ratification convention propose amendments? And what is the difference between proposing recommendation amendments and conditional amendments? Proponents of the Constitution urged the former and hoped that the Massachusetts Compromise—ratify now, amend later—proposed by Hancock and supported by Adams and Ames would become the model for the remainder of the ratification campaign across the country. There is some disagreement about what the likely vote in favor and against was going into the convention, but it was at least even and may have been tilted toward the Antifederalists. What is clear is that the Massachusetts Compromise secured the victory for the proponents of the Constitution because roughly 10 delegates changed their mind to secure ratification by a 187-168 vote. Rev. Isaac Bachus, Nathaniel Barrell (Massachusetts), William Symmes Jr. and Charles Turner, the leader of the Antifederalists, were four of those delegates. Orin Grant Libby identified Barrell of York County as a delegate who defied the instructions of his constituents, and Jackson Turner Main identified 14 defectors from the Antifederalist cause.

It would be remiss not to note that after the vote was taken, no fewer than eight of the delegates who voted to reject the Constitution—including vociferous opponents Samuel Nason, Benjamin Randall, John Taylor, and William Widgery of the independent Maine movement—promised to work with their constituents to support the Constitution. And Gerry? “Crest-fallen but acquiesces.”

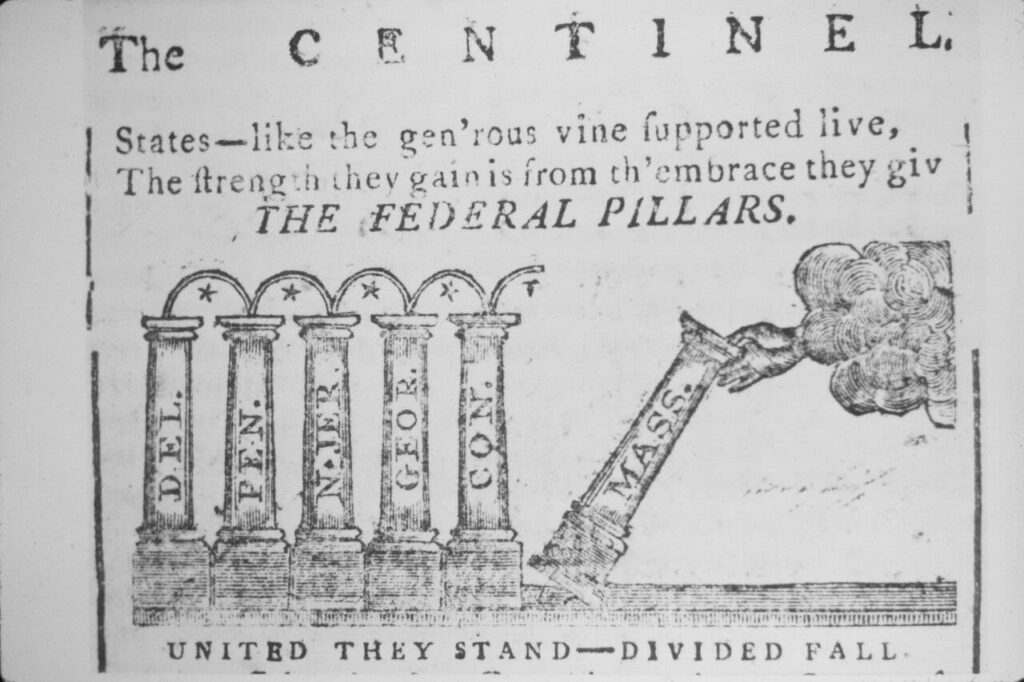

This is first time that the newspapers showed the five pillars supporting, and then you have the Massachusetts pillar going up. They were now six federal pillars rising as the structure holding up the Constitution. So this is primitive campaigning, but at the same time, it shows “consent of the governed” at work. It shows the origin of party politics, of precincts, of campaigning, of debating, of campaign literature, and of the involvement of newspapers.

New Hampshire

Many a campaign has fallen on hard times in New Hampshire in February, and as New Hampshire goes, so some pundits have stated, so goes the rest of the nation. Well, they have these two ratifying conventions taking place in the northeast. The New Hampshire convention met on February 13. To the surprise of the pro-Constitution forces, it was discovered that a majority of the delegates were actually opposed to ratification! Of the 108 delegates in attendance, fewer than 50 were in favor of adoption. According to Jackson Turner Main, “only thirty favored ratification.” And the going was so tough that the Madisonian forces proposed a strategy that they implemented on February 22. The strategy in New Hampshire was to adjourn in order to avoid what was beginning to look like the first ratification defeat. So they postponed with the intention of coming back later. That’s the low-ground explanation for the delay. The high-ground explanation was that the delay allowed the delegates who were elected, perhaps even instructed by their constituents to oppose ratification, before they knew that five states would ratify before New Hampshire’s convention even met, to go back to their district and make sure that their constituency still felt the same way about rejecting the Constitution.

Philadelphia Constitutional Convention delegate John Langdon moved for a postponement. It passed 56-51 on February 24, the site was moved to Concord, and the next ratifying convention was scheduled to meet in June. Whether they were stupid or they were simply persuaded to take the high ground, the Antifederalist forces agreed to postpone the conversation. The question is this: who would benefit from the postponement in New Hampshire?