Second Continental Congress: February 9, 1776

February 9, 1776

Congress focuses on receiving memorials on trade, reading letters from Generals, and providing sufficient ammunition. Massachusetts select their five member delegation for 1776 and John Adams is a member. He provides an account of the Maryland delegation’s successful efforts in 1775 to prevent him from being a representative in Congress AND Chief Justice of Massachusetts. He attributes this move in favor of one person, one job, to “the partisans in opposition to independence.”

Link to date-related documents.

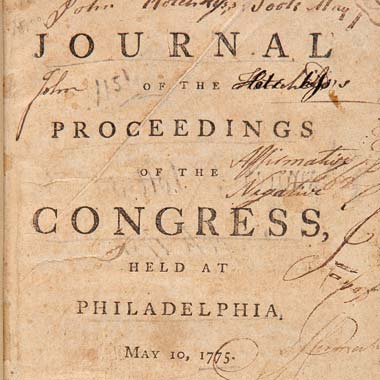

Journals of the Continental Congress [Edited]

John Hancock, Samuel Adams, John Adams, Robert Treat Paine, and Elbridge Gerry, were chosen to represent Massachusetts in “the American Congress,” until January 1, 1777.

[Editor’s Note. John Adams was appointed Chief Justice of Massachusetts in October, 1775. Consequently, he was absent from the Second Continental Congress meeting in Philadelphia between December 1775 and early February 1776, when he resigned from the Court and returned to Congress.]

The presence of one member constituted a quorum. Their objective remains the same as in 1775: “to concert, direct, and order such farther measures, as shall to them appear best calculated for the establishment of right and liberty to the American colonies, upon a basis permanent and secure, against the power and arts of the British administration, and guarded against any future encroachments of their enemies, with power to adjourn to such times and places, as shall appear most conducive to the public safety and advantage.”

Resolved, that the letters and papers recently received from Generals Washington, Schuyler, and Arnold, as well Governor Trumbull, be referred to a committee of five: Samuel Chase, John Adams, John Penn, George Wythe, and Edward Rutledge.

Two letters arrived from the Convention of New Jersey, dated February 6, 1776. The first one respecting tea was postponed until Monday. The other recommended “proper persons for field officers of the third battalion.” Congress elected three.

A Memorial from Mr. Kirkland was presented to Congress, read, and ordered lie on the table.

The Congress took into consideration the report of the Committee on the second memorial of Sansom, Murray, & Co. &c.

Resolved, That the memorialists be permitted to make sale of their cargo of wheat in Connecticut, or else to proceed on their original voyage to Falmouth, in England, and a market under the office papers, and clearances, which the said vessel sailed with from New York in September last: and also subject to the former restrictions of Congress, respecting the appointment of a commander.

Resolved, That a copy of the paper relating to signals found among the intercepted letters, be sent to the commander of the fleet, and that the delegates of the several colonies be permitted to send to their respective conventions or committees of safety a copy of the said paper under a strong injunction to keep it secret.

Congress, once again, became involved in the production and distribution of gun powder and the presence of salt petre.

A memorial from Stacey Hepburn was presented to Congress, read, and referred to a committee of three: Thomas Mc’Kean, Thomas Nelson, and John Penn.

Adjourned to 10 o’Clock on Monday next.

John Adams, Autobiography (Writings, III, p. 25.)

I soon found there was a whispering among the partisans in opposition to independence, that I was interested; that I held an office under the new government of Massachusetts; that I was afraid of losing it, if we did not declare independence; and that I consequently ought not to be attended to. This they circulated so successfully, that they got it insinuated among the members of the legislature in Maryland, where their friends were powerful enough to give an instruction to their delegates in Congress, warning them against listening to the advice of interested persons, and manifestly pointing me out to the understanding of every one. This instruction was read in Congress. It produced no other effect upon me than a laughing letter to my friend, Mr. Chase, who regarded it no more than I did. These chuckles I was informed of, and witnessed for many weeks, and at length they broke out in a very extraordinary manner.

When I had been speaking one day on the subject of independence, or the institution of governments, which I always considered as the same thing, a gentleman of great fortune and high rank arose and said, he should move, that no person who held an office under a new government should be admitted to vote on any such question, as they were interested persons. I wondered at the simplicity of this motion, but knew very well what to do with it.

I rose from my seat with great coolness and deliberation; so far from expressing or feeling any resentment, I really felt gay, though as it happened, I preserved an unusual gravity in my countenance and air, and said, “Mr. President, I will second the gentleman’s motion, and I recommend it to the honorable gentleman to second another which I should make, namely, that no gentleman who holds any office under the old or present government should be admitted to vote on any such question, as they were interested persons.” The moment when this was pronounced, it flew like an electric stroke through every countenance in the room, for the gentleman who made the motion held as high an office under the old government as I did under the new, and many other members present held offices under the royal government.

My friends accordingly were delighted with my retaliation, and the friends of my antagonist were mortified at his indiscretion in exposing himself to such a retort. Finding the house in a good disposition to hear me, I added, I would go further, and cheerfully consent to a self-denying ordinance, that every member of Congress, before we proceeded to any question respecting independence, should take a solemn oath never to accept or hold any office of any kind in America after the revolution. Mr. Wythe, of Virginia, rose here, and said Congress had no right to exclude any of their members from voting on these questions; their constituents only had a right to restrain them; and that no member had a right to take, nor Congress to prescribe any engagement not to hold offices after the revolution or before. Again I replied, that whether the gentleman’s opinion was well or ill founded, I had only said that I was willing to consent to such an arrangement. That I knew very well what these things meant. They were personal attacks upon me, and I was glad that at length they had been made publicly where I could defend myself. That I knew very well that they had been made secretly and circulated in whispers, not only in the city of Philadelphia and State of Pennsylvania, but in the neighboring States, particularly Maryland, and very probably in private letters throughout the Union.

I now took the opportunity to declare in public, that it was very true, the unmerited and unsolicited, though unanimous good will of the Council of Massachusetts, had appointed me to an important office, that of Chief Justice; that as this office was a very conspicuous station, and consequently a dangerous one, I had not dared to refuse it, because it was a post of danger, though by the acceptance of it, I was obliged to relinquish another office,–meaning my barrister’s office–which was more than four times as profitable. That it was a sense of duty, and a full conviction of an honest cause, and not any motives of ambition, or hopes of honor, or profit, which had drawn me into my present course. That, I had seen enough already in the course of my own experience to know that the American cause was not the most promising road to profits, honors, power, or pleasure. That on the contrary, a man must renounce all these and devote himself to labor, danger and death, and very possibly to disgrace and infamy, before he was fit in my judgment, in the present state and future prospects of the country, for a seat in that Congress.

This whole scene was a comedy to Charles Thompson, whose countenance was in raptures all the time. When all was over, he told me…he had been witness to many of their conversations, in which they had endeavored to excite and propagate prejudices against me, on account of my office of Chief Justice…. No more, indeed, were made in my presence, but the party did not cease to abuse me in their secret circles on this account, as I was well informed. Not long afterwards, hearing that the Supreme Court in Massachusetts was organized and proceeding very well on the business of their circuits, I wrote my resignation of the office of Chief Justice, to the Council.”

Edited with commentary by Gordon Lloyd.

Journals of the Continental Congress

Journals of the Continental Congress