First Continental Congress: October 21, 1774

October 21, 1774

A draft of an Address to the People of Great Britain King, by John Jay, and a Memorial to the Inhabitants of Colonial America, by Richard Henry Lee, were debated. Jay appealed to the traditional rights of Englishmen. “Place us in the same situation that we were at the close of the last war, and our former harmony will be restored.” Lee agreed: “Soon after the conclusion of the late war, there commenced a memorable change in the treatment of these Colonies.” John Dickinson was added to the Committee to Address the King.

Link to date-related documents.

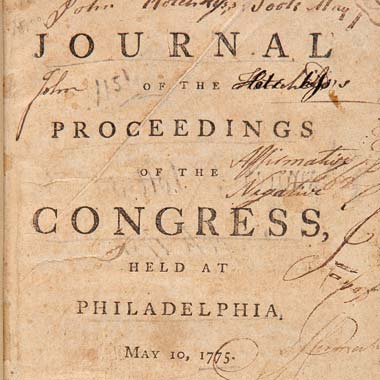

Journals of the Continental Congress [Edited]

The Address to the People of Great-Britain

To the people of Great-Britain, from the delegates appointed by the several English colonies of New-Hampshire, Massachusetts-Bay, Rhode-Island and Providence Plantations, Connecticut, New-York, New-Jersey, Pennsylvania, the lower counties on Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, North-Carolina, and South-Carolina, to consider of their grievances in general Congress.

Friends and fellow subjects,

WHEN a Nation, led to greatness by the hand of Liberty, and possessed of all the glory that heroism, munificence, and humanity can bestow, descends to the ungrateful task of forging chains for her Friends and Children, and instead of giving support to Freedom, turns advocate for Slavery and Oppression, there is reason to suspect she has either ceased to be virtuous, or been extremely negligent in the appointment of her rulers.

In almost every age, in repeated conflicts, in long and bloody wars, as well civil as foreign, against many and powerful nations, against the open assaults of enemies, and the more dangerous treachery of friends, have the inhabitants of your island, your great and glorious ancestors, maintained their independence and transmitted the rights of men, and the blessings of liberty to you their posterity.

Be not surprised therefore, that we, who are descended from the same common ancestors; that we, whose forefathers participated in all the rights, the liberties, and the constitution, you so justly boast [of], and who have carefully conveyed the same fair inheritance to us, guarantied by the plighted faith of government and the most solemn compacts with British Sovereigns, should refuse to surrender them to men, who found their claims on no principles of reason, and who prosecute them with a design, that by having our lives and property in their power, they may with the greater facility enslave you.

The cause of America is now the object of universal attention: it has at length become very serious. This unhappy country has not only been oppressed, but abused and misrepresented; and the duty we owe to ourselves and posterity, to your interest, and the general welfare of the British empire, leads us to address you on this very important subject.

Know then, That we consider ourselves, and do insist, that we are and ought to be, as free as our fellow-subjects in Britain, and that no power on earth has a right to take our property from us without our consent.

That we claim all the benefits secured to the subject by the English constitution, and particularly that inestimable one of trial by jury.

That we hold it essential to English Liberty, that no man be condemned unheard, or punished for supposed offences, without having an opportunity of making his defense.

That we think the Legislature of Great-Britain is not authorized by the constitution1 to establish a religion, fraught with sanguinary and impious tenets, or, to erect an arbitrary form of government, in any quarter of the globe. These rights, we, as well as you, deem sacred. And yet sacred as they are, they have, with many others, been repeatedly and flagrantly violated.

Are not the Proprietors of the soil of Great-Britain Lords of their own property? can it be taken from them without their consent? will they yield it to the arbitrary disposal of any man, or number of men whatever?–You know they will not.

Why then are the Proprietors of the soil of America less Lords of their property than you are of yours, or why should they submit it to the disposal of your Parliament, or any other Parliament, or Council in the world, not of their election? Can the intervention of the sea that divides us, cause disparity in rights, or can any reason be given, why English subjects, who live three thousand miles from the royal palace, should enjoy less liberty than those who are three hundred miles distant from it?

Reason looks with indignation on such distinctions, and freemen can never perceive their propriety. And yet, however chimerical and unjust such discriminations are, the Parliament assert, that they have a right to bind us in all cases without exception, whether we consent or not; that they may take and use our property when and in what manner they please; that we are pensioners on their bounty for all that we possess, and can hold it no longer than they vouchsafe to permit. Such declarations we consider as heresies in English polities, and which can no more operate to deprive us of our property, than the interdicts of the Pope can divest Kings of scepters which the laws of the land and the voice of the people have placed in their hands.

At the conclusion of the late war–a war rendered glorious by the abilities and integrity of a Minister, to whose efforts the British empire owes its safety and its fame: At the conclusion of this war, which was succeeded by an inglorious peace, formed under the auspices of a Minister of principles, and of a family unfriendly to the protestant cause, and inimical to liberty.–We say at this period, and under the influence of that man, a plan for enslaving your fellow subjects in America was concerted, and has ever since been pertinaciously carrying into execution.

Prior to this era you were content with drawing from us the wealth produced by our commerce. You restrained our trade in every way that could conduce to your emolument. You exercised unbounded sovereignty over the sea. You named the ports and nations to which alone our merchandise should be carried, and with whom alone we should trade; and though some of these restrictions were grievous, we nevertheless did not complain; we looked up to you as to our parent state, to which we were bound by the strongest ties: And were happy in being instrumental to your prosperity and your grandeur.

We call upon you yourselves, to witness our loyalty and attachment to the common interest of the whole empire: Did we not, in the last war, add all the strength of this vast continent to the force which repelled our common enemy? Did we not leave our native shores, and meet disease and death, to promote the success of British arms in foreign climates? Did you not thank us for our zeal, and even reimburse us large sums of money, which, you confessed, we had advanced beyond our proportion and far beyond our abilities? You did.

To what causes, then, are we to attribute the sudden change of treatment, and that system of slavery which was prepared for us at the restoration of peace?

Before we had recovered from the distresses which ever attend war, an attempt was made to drain this country of all its money, by the oppressive Stamp-Act. Paint, Glass, and other commodities, which you would not permit us to purchase of other nations, were taxed; nay, although no wine is made in any country, subject to the British state, you prohibited our procuring it of foreigners, without paying a tax, imposed by your parliament, on all we imported. These and many other impositions were laid upon us most unjustly and unconstitutionally, for the express purpose of raising a Revenue.–In order to silence complaint, it was, indeed, provided, that this revenue should be expended in America for its protection and defense.–These exactions, however, can receive no justification from a pretended necessity of protecting and defending us. They are lavishly squandered on court favorites and ministerial dependents, generally avowed enemies to America and employing themselves, by partial representations, to traduce and embroil the Colonies. For the necessary support of government here, we ever were and ever shall be ready to provide. And whenever the exigencies of the state may require it, we shall, as we have heretofore done, cheerfully contribute our full proportion of men and money. To enforce this unconstitutional and unjust scheme of taxation, every fence that the wisdom of our British ancestors had carefully erected against arbitrary power, has been violently thrown down in America, and the inestimable right of trial by jury taken away in cases that touch both life and property.–It was ordained, that whenever offences should be committed in the colonies against particular Acts imposing various duties and restrictions upon trade, the prosecutor might bring his action for the penalties in the Courts of Admiralty; by which means the subject lost the advantage of being tried by an honest uninfluenced jury of the vicinage, and was subjected to the sad necessity of being judged by a single man, a creature of the Crown, and according to the course of a law which exempts the prosecutor from the trouble of proving his accusation, and obliges the defendant either to evince his innocence or to suffer. To give this new judicatory1 the greater importance, and as, if with design to protect false accusers, it is further provided, that the Judge’s certificate of there having been probable causes of seizure and prosecution, shall protect the prosecutor from actions at common law for recovery of damages.

By the course of our law, offences committed in such of the British dominions in which courts are established and justice duel and regularly administered, shall be there tried by a jury of the vicinage. There the offenders and the witnesses are known, and the degree of credibility to be given to their testimony, can be ascertained.

In all these Colonies, justice is regularly and impartially administered, and yet by the construction of some, and the direction of other Acts of Parliament, offenders are to be taken by force, together with all such persons as may be pointed out as witnesses, and carried to England, there to be tried in a distant land, by a jury of strangers, and subject to all the disadvantages that result from want of friends, want of witnesses, and want of money.

When the design of raising a revenue from the duties imposed on the importation of tea into America had in great measure been rendered abortive by our ceasing to import that commodity, a scheme was concerted by the Ministry with the East-India Company, and an Act passed enabling and encouraging them to transport and vend it in the colonies. A ware of the danger of giving success to this insidious manoeuvre, and of permitting a precedent of taxation thus to be established among us, various methods were adopted to elude the stroke. The people of Boston, then ruled by a Governor, whom, as well as his predecessor Sir Francis Bernard, all America considers as her enemy, were exceedingly embarrassed. The ships which had arrived with the tea were by his management prevented from returning.–The duties would have been paid; the cargoes landed and exposed to sale; a Governor’s influence would have procured and protected many purchasers. While the town was suspended by deliberations on this important subject, the tea was destroyed. Even supposing a trespass was thereby committed, and the Proprietors of the tea entitled to damages.–The Courts of Law were open, and Judges appointed by the Crown presided in them.–The East India Company however did not think proper to commence any suits, nor did they even demand satisfaction, either from individuals or from the community in general. The Ministry, it seems, officiously made the case their own, and the great Council of the nation descended to intermeddle with a dispute about private property.–Divers papers, letters, and other unauthenticated ex parte evidence were laid before them; neither the persons who destroyed the Tea, or the people of Boston, were called upon to answer the complaint. The Ministry, incensed by being disappointed in a favorite scheme, were determined to recur from the little arts of finesse, to open force and unmanly violence. The port of Boston was blocked up by a fleet, and an army placed in the town. Their trade was to be suspended, and thousands reduced to the necessity of gaining subsistence from charity, till they should submit to pass under the yoke, and consent to become slaves, by confessing the omnipotence of Parliament, and acquiescing in whatever disposition they might think proper to make of their lives and property.

Let justice and humanity cease to be the boast of your national consult your history, examine your records of former transactions, nay turn to the annals of the many arbitrary states and kingdoms that surround you, and shew us a single instance of men being condemned to suffer for imputed crimes, unheard, unquestioned, and without even the specious formality of a trial; and that too by laws made expressly for the purpose, and which had no existence at the time of the fact committed. If it be difficult to reconcile these proceedings to the genius and temper of your laws and constitution, the task will become more arduous when we call upon our ministerial enemies to justify, not only condemning men untried and by hearsay, but involving the innocent in one common punishment with the guilty, and for the act of thirty or forty, to bring poverty, distress and calamity on thirty thousand souls, and those not your enemies, but your friends, brethren, and fellow subjects.

It would be some consolation to us, if the catalogue of American oppressions ended here. It gives us pain to be reduced to the necessity of reminding you, that under the confidence reposed in the faith of government, pledged in a royal charter from a British Sovereign, the fore-fathers of the present inhabitants of the Massachusetts-Bay left their former habitations, and established that great, flourishing, and loyal Colony. Without incurring or being charged with a forfeiture of their rights, without being heard, without being tried, without law, and without justice, by an Act of Parliament, their charter is destroyed, their liberties violated, their constitution and form of government changed: And all this upon no better pretence, than because in one of their towns a trespass was committed on some merchandize, said to belong to one of the Companies, and because the Ministry were of opinion, that such high political regulations were necessary to compel due subordination and obedience to their mandates.

Nor are these the only capital grievances under which we labor. We might tell of dissolute, weak and wicked Governors having been set over us; of Legislatures being suspended for asserting the rights of British subjects–of needy and ignorant dependents on great men, advanced to the seats of justice and to other places of trust and importance;–of hard restrictions on commerce, and a great variety of lesser evils, the recollection of which is almost lost under the weight and pressure of greater and more poignant calamities.

Now mark the progression of the ministerial plan for enslaving us.

Well aware that such hardy attempts to take our property from us; to deprive us of that valuable right of trial by jury; to seize our persons, and carry us for trial to Great-Britain; to blockade our ports; to destroy our Charters, and change our forms of government, would occasion, and had already occasioned, great discontent in all the Colonies, which might produce opposition to these measures: An Act was passed to protect, indemnify, and screen from punishment such as might be guilty even of murder, in endeavoring to carry their oppressive edicts into execution; And by another Act the dominion of Canada is to be so extended, modelled, and governed, as that by being disunited from us, detached from our interests, by civil as well as religious prejudices, that by their numbers daily swelling with Catholic emigrants from Europe, and by their devotion to Administration, so friendly to their religion, they might become formidable to us, and on occasion, be fit instruments in the hands of power, to reduce the ancient free Protestant Colonies to the same state of slavery with themselves.

This was evidently the object of the Act:–And in this view, being extremely dangerous to our liberty and quiet, we cannot forebear complaining of it, as hostile to British America.–Suppurated to these considerations, we cannot help deploring the unhappy condition to which it has reduced the many English settlers, who, encouraged by the Royal Proclamation, promising the enjoyment of all their rights, have purchased estates in that country.–They are now the subjects of an arbitrary government, deprived of trial by jury, and when imprisoned cannot claim the benefit of the habeas corpus Act, that great bulwark and palladium of English liberty:–Nor can we suppress our astonishment, that a British Parliament should ever consent to establish in that country a religion that has deluged your island in blood, and dispersed impiety, bigotry, persecution, murder and rebellion through every part of the world.

This being a true state of facts, let us beseech you to consider to what end they lead.

Admit that the Ministry, by the powers of Britain, and the aid of our Roman Catholic neighbors, should be able to carry the point of taxation, and reduce us to a state of perfect humiliation and slavery. Such an enterprise would doubtless make some addition to your national debt, which already presses down your liberties, and fills you with Pensioners and Placemen.–We presume, also, that your commerce will somewhat be diminished. However, suppose you should prove victorious–in what condition will you then be? What advantages or what laurels will you reap from such a conquest?

May not a Ministry with the same armies enslave you–It may be said, you will cease to pay them–but remember the taxes from America, the wealth, and we may add, the men, and particularly the Roman Catholics of this vast continent will then be in the power of your enemies–nor will you have any reason to expect, that after making slaves of us, many among us should refuse to assist in reducing you to the same abject state. Do not treat this as chimerical–Know that in less than half a century, the quit-rents reserved to the Crown, from the numberless grants of this vast continent, will pour large streams of wealth into the royal coffers, and if to this be added the power of taxing America at pleasure, the Crown will be rendered independent on [of] you for supplies, and will possess more treasure than may be necessary to purchase the remains of Liberty in your Island–In a word, take care that you do not fall into the pit that is preparing for us.

We believe there is yet much virtue, much justice, and much public spirit in the English nation–To that justice we now appeal. You have been told that we are seditious, impatient of government and desirous of independence. Be assured that these are not facts, but calumnies.–Permit us to be as free as yourselves, and we shall over esteem a union with you to be our greatest glory and our greatest happiness, we shall ever be ready to contribute all in our power to the welfare of the Empire–we shall consider your enemies as our enemies, and your interest as our own.

But if you are determined that your Ministers shall wantonly sport with the rights of Mankind–If neither the voice of justice, the dictates of the law, the principles of the constitution, or the suggestions of humanity can restrain your hands from shedding human blood in such an impious cause, we must then tell you, that we will never submit to be hewers of wood or drawers of water for any ministry or nation in the world.

Place us in the same situation that we were at the close of the last war, and our former harmony will be restored.

But lest the same supineness and the same inattention to our common interest, which you have for several years shewn, should continue, we think it prudent to anticipate the consequences.

By the destruction of the trade of Boston, the Ministry have endeavored to induce submission to their measures.–The like fate may befall us all, we will endeavor therefore to live without trade, and recur for subsistence to the fertility and bounty of our native soil, which will afford us all the necessaries and some of the conveniences of life.–We have suspended our importation from Great Britain and Ireland; and in less than a year’s time, unless our grievances should be redressed, shall discontinue our exports to those kingdoms and the West-Indies.

It is with the utmost regret, however, that we find ourselves compelled by the overruling principles of self-preservation, to adopt measures detrimental in their consequences to numbers of our fellow subjects in Great Britain and Ireland. But we hope, that the magnanimity and justice of the British Nation will furnish a Parliament of such wisdom, independence and public spirit, as may save the violated rights of the whole empire from the devices of wicked Ministers and evil Counsellors whether in or out of office, and thereby restore that harmony, friendship and fraternal affection between all the Inhabitants of his Majesty’s kingdoms and territories, so ardently wished for by every true and honest American.

Memorial to the Inhabitants of the British Colonies

To the inhabitants of the colonies of New-Hampshire, Massachusetts-Bay, Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, Connecticut, New-York, New-Jersey, Pennsylvania, the counties of New Castle, Kent and Sussex, on Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, North-Carolina and South-Carolina:

Friends and fellow countrymen,

We, the Delegates appointed by the good people of the above Colonies to meet at Philadelphia in September last, for the purposes mentioned by our respective Constituents, have in pursuance of the trust reposed in us, assembled, and taken into our most serious consideration the important matters recommended to the Congress. Our resolutions thereupon will be herewith communicated to you. But as the situation of public affairs grows daily more and more alarming; and as it may be more satisfactory to you to be informed by us in a collective body, than in any other manner, of those sentiments that have been approved, upon a full and free discussion by the Representatives of so great a part of America, we esteem ourselves obliged to add this Address to these Resolutions.

In every case of opposition by a people to their rulers, or of one state to another, duty to Almighty God, the creator of all, requires that a true and impartial judgment be formed of the measures leading to such opposition; and of the causes by which it has been provoked, or can in any degree be justified: That neither affection on the one hand, nor resentment on the other, being permitted to give a wrong bias to reason, it may be enabled to take a dispassionate view of all circumstances, and settle the public conduct on the solid foundations of wisdom and justice.

From Councils thus tempered arise the surest hopes of the divine favor, the firmest encouragement to the parties engaged and the strongest recommendation of their cause to the rest of mankind.

With minds deeply impressed by a sense of these truths, we have diligently, deliberately and calmly enquired into and considered those exertions, both of the legislative and executive power of Great-Britain, which have excited so much uneasiness in America, and have with equal fidelity and attention considered the conduct of the Colonies. Upon the whole, we find ourselves reduced to the disagreeable alternative, of being silent and betraying the innocent, or of speaking out and censuring those we wish to revere.–In making our choice of these distressing difficulties, we prefer the course dictated by honesty, and a regard for the welfare of our country.

Soon after the conclusion of the late war, there commenced a memorable change in the treatment of these Colonies. By a statute made in the fourth year of the present reign, a time of profound peace, alleging, “the expediency of new provisions and regulations for extending the commerce between Great-Britain and his majesty’s dominions in America, and the necessity of raising a Revenue in the said dominions for defraying the expenses of defending, protecting” and securing the same, the Commons of Great-Britain undertook to give and grant to his Majesty many rates and duties, to be paid in these Colonies. To enforce the observance of this Act, it prescribes a great number of severe penalties and forfeitures; and in two sections makes a remarkable distinction between the subjects in Great-Britain and those in America. By the one, the penalties and forfeitures incurred there are to be recovered in any of the King’s Courts of Record, at Westminster, or in the Court of Exchequer in Scotland; and by the other, the penalties and forfeitures incurred here are to be recovered in any Court of Record, or in any Court of Admiralty, or Vice-Admiralty, at the election of the informer or prosecutor.

The Inhabitants of these Colonies confiding in the justice of Great-Britain, were scarcely allowed sufficient time to receive and consider this Act, before another, well known by the name of the Stamp Act, and passed in the fifth year of this reign, engrossed their whole attention. By this statute the British Parliament exercised, in the most explicit manner a power of taxing us, and extending the jurisdiction of the courts of Admiralty and Vice-Admiralty in the Colonies, to matters arising within the body of a county, directed the numerous penalties and forfeitures, thereby inflicted, to be recovered in the said courts.

In the same year a tax was imposed upon us, by an Act, establishing several new fees in the customs. In the next year, the Stamp-Act was repealed; not because it was founded in an erroneous principle, but us the repealing Act recites, because the continuance thereof would be attended with many inconveniences, and might be productive of consequences “greatly detrimental to the commercial interest of Great-Britain.”

In the same year, and by a subsequent Act, it was declared, that “his Majesty in Parliament, of right, had power to bind the people of these Colonies, By Statutes, in all cases whatsoever.”

In the same year, another Act was passed, for imposing rates and duties payable in these Colonies. In this Statute the Commons avoiding the terms of giving and granting, “humbly besought his Majesty, that it might be enacted, &c.” But from a declaration in the preamble, that the rates and duties were “in lieu of” several others granted by the Statute first before mentioned for raising a revenue and from some other expressions it appears, that these duties were intended for that purpose.

In the next year, (1767) an Act was made to enable his Majesty “to put the customs, and other duties in America, under the management of Commissioners, &c.” and the King thereupon erected the present expensive Board of Commissioners, for the express purpose of carrying into execution the several Acts relating to the revenue and trade in America.

After the repeal of the Stamp-Act, having again resigned ourselves to our ancient unsuspicious affections for the parent state, and anxious to avoid any controversy with her, in hopes of a favorable alteration in sentiments and measures towards us, we did not press our objections against the above mentioned Statutes made subsequent to that repeal.

Administration attributing to trifling causes, a conduct that really proceeded from generous motives, were encouraged in the same year (1767) to make a bolder experiment on the patience of America.

By a Statute commonly called the Glass, Paper and Tea Act, made fifteen months after the repeal of the Stamp-Act, the Commons of Great-Britain resumed their former language, and again undertook to “give and grant rates and duties to be paid in these Colonies,” for the express purpose of “raising a revenue, to defray the charges of the administration of justice, the support of civil government, and defending the King’s dominions,” on this continent. The penalties and forfeitures, incurred under this Statute, are to be recovered in the same manner, with those mentioned in the foregoing Acts.

To this Statute, so naturally tending to disturb the tranquility then universal throughout the Colonies, Parliament, in the same scission, added another no less extraordinary.

Ever since the making the present peace, a standing army has been kept in these Colonies. From respect for the mother country, the innovation was not only tolerated, but the provincial Legislatures generally made provision for supplying the troops.

The Assembly of the province of New York, having passed an Act of this kind, but differing in some articles, from the directions of the Act of Parliament made in the fifth year of this reign, the House of Representatives in that Colony was prohibited by a Statute made in the session last mentioned, from making any bill, order, resolution or vote, except for adjourning or choosing a Speaker, until provision should be made by the said Assembly for furnishing the troops, within that province, not only with all such necessaries as were required by the Statute which they were charged with disobeying, but also with those required by two other subsequent Statutes, which were declared to be in force until the twenty fourth day of March 1769.

These Statutes of the year 1767 revived the apprehensions and discontents, that had entirely subsided on the repeal of the Stamp-Act; and amidst the just fears and jealousies thereby occasioned, a Statute was made in the next year (1768) to establish Courts of Admiralty and Vice-Admiralty on a new model, expressly for the end of more effectually recovering of the penalties and forfeitures inflicted by Acts of Parliament, framed for the purpose of raising a revenue in America, &c.

The immediate tendency of these statutes is, to subvert the right of having a share in legislation, by rendering Assemblies useless; the right of property, by taking the money of the Colonists without their consent; the right of trial by jury, by substituting in their place trials in Admiralty and Vice-Admiralty courts, where single Judges preside, holding their Commissions during pleasure; and unduly to influence the Courts of common law, by rendering the Judges thereof totally dependent on the Crown for their salaries.

These statutes, not to mention many others exceedingly exceptionable, compared one with another, will be found, not only to form a regular system, in which every part has great force, but also a pertinacious adherence to that system, for subjugating these Colonies, that are not, and, from local circumstances, cannot be represented in the House of Commons, to the uncontrollable and unlimited power of Parliament, in violation of their undoubted rights and liberties, in contempt of their humble and repeated supplications.

This conduct must appear equally astonishing and unjustifiable, when it is considered how unprovoked it has been by any behavior of these Colonies. From their first settlement, their bitterest enemies never fixed on any of them a charge of disloyalty to their Sovereign, or disaffection to their Mother-Country. In the wars she has carried on, they have exerted themselves whenever required, in giving her assistance; and have rendered her services, which she has publicly acknowledged to be extremely important. Their fidelity, duty and usefulness during the last war, were frequently and affectionately confessed by his late Majesty and the present King.

The reproaches of those, who are most unfriendly to the freedom of America, are principally levelled against the province of Massachusetts-Bay; but with what little reason, will appear by the following declarations of a person, the truth of whose evidence, in their favor, will not be questioned.–Governor Bernard thus addresses the two Houses of Assembly–in his speech on the 24th of April, 1762,- “Tho unanimity and dispatch, with which you have complied with the requisitions of his Majesty, require my particular acknowledgment. And it gives me additional pleasure to observe, that you have therein acted under no other influence than a due sense of your duty, both as members of a general empire, and as the body of a particular province.”

In another speech on the 27th of May, in the same year, he says, “Whatever shall be the event of the war, it must be no small satisfaction to us, that this province hath contributed its full share to the support of it. Everything that hath been required of it hath been complied with; and the execution of the powers committed to me, for raising the provincial troops hath been as full and complete as the grant of them. Never before were regiments so easily levied, so well composed, and so early in the field as they have been this year: the common people seemed to be animated with the spirit of the general Court, and to vie with them in their readiness to serve the King.”

Such was the conduct of the People of the Massachusetts-Bay, during the last war. As to their behavior before that period, it ought not to have been forgot in Great-Britain, that not only on every occasion they had constantly and cheerfully complied with the frequent royal requisitions–but that chiefly by their vigorous efforts, Nova-Scotia was subdued in 1710, and Louisbourg in 1745.

Foreign quarrels being ended, and the domestic disturbances, that quickly succeeded on account of the stamp-act, being quieted by its repeal, the Assembly of Massachusetts-Bay transmitted a humble address of thanks to the King and divers noblemen, and soon after passed a bill for granting compensation to the sufferers in the disorder occasioned by that act.

These circumstances and the following extracts from Governor Bernard’s letters in 1768, to the Earl of Shelburne, Secretary of State, clearly shew, with what grateful tenderness they strove to bury in oblivion the unhappy occasion of the late discords, and with what respectful reluctance1 they endeavored to escape other subjects of future controversy….

The vindication of the province of Massachusetts-Bay contained in these Letters will have greater force, if it be considered, that they were written several months after the fresh alarm given to the colonies by the statutes passed in the preceding year.

In this place it seems proper to take notice of the insinuation in one of these statutes, that the interference of Parliament was necessary to provide for “defraying the charge of the administration of justice, the support of civil government, and defending the King’s dominions in America.”

As to the two first articles of expense, every colony had made such provision, as by their respective Assemblies, the best judges on such occasions, was thought expedient, and suitable to their several circumstances. Respecting the last, it is well known to all men, the least acquainted with American affairs, that the colonies were established, and have generally defended themselves, without the least assistance from Great-Britain; and, that at the time of her taxing them by the statutes before mentioned, most of them were laboring under very heavy debts contracted in the last war. So far were they from sparing their money, when their Sovereign, constitutionally, asked their aids, that during the course of that war, Parliament repeatedly made them compensations for the expenses of those strenuous efforts, which, consulting their zeal rather than their strength, they had cheerfully incurred.

Severe as the Acts of Parliament before mentioned are, yet the conduct of Administration hath been equally injurious, and irritating to this devoted country.

Under pretense of governing them, so many new institutions, uniformly rigid and dangerous, have been introduced, as could only be expected from incensed masters, for collecting the tribute or rather the plunder of conquered provinces.

By an order of the King, the authority of the Commander in chief, and under him, of the Brigadiers general, in time of peace, is rendered supreme in all the civil governments, in America; and thus an uncontrollable military power is vested in officers not known to the constitution of these colonies.

A large body of troops and a considerable armament of ships of war, have been sent to assist in taking their money without their consent.

Expensive and oppressive offices have been multiplied, and the acts of corruption industriously practiced to divide and destroy.

The Judges of the Admiralty and Vice-Admiralty Courts are impowered to receive their salaries and fees from the effects to be condemned by themselves; the Commissioners of the customs are impowered to break open and enter houses without the authority of any civil magistrate founded on legal information.

Judges of Courts of Common Law have been made entirely dependent on the Crown for their commissions and salaries.

A court has been established at Rhode-Island, for the purposes of taking Colonists to England to be tried.

Humble and reasonable petitions from the Representatives of the people have been frequently treated with contempt; and Assemblies have been repeatedly and arbitrarily dissolved.

From some few instances it will sufficiently appear, on what presences of justice those dissolutions have been founded.

The tranquility of the colonies having been again disturbed, as has been mentioned, by the statutes of the year 1767, the Earl of Hillsborough, Secretary of State, in a letter to Governor Bernard, dated April 22, 1768, censures the “presumption” of the House of Representatives for “resolving upon a measure of so inflammatory a nature as that of writing to the other colonies, on the subject of their intended representations against some late Acts of Parliament,” then declares that “his Majesty considers this step as evidently tending to create unwarrantable combinations to excite an unjustifiable opposition to the constitutional authority of Parliament:”–and afterwards adds, “It is the King’s pleasure, that as soon as the General Court is again assembled, at the time prescribed by the Charter, you should require of the House of Representatives, in his Majesty’s name, to rescind the resolution which gave birth to the circular letter from the Speaker, and to declare their disapprobation of, and dissent to that rash and “hasty proceeding.”

If the new Assembly should refuse to comply with his Majesty’s “reasonable expectation, it is the King’s pleasure, that you should “immediately dissolve them.”

This letter being laid before the House, and the resolution not being rescinded according to the order, the Assembly was dissolved. A letter of a similar nature was sent to other Governors to procure resolutions approving the conduct of the Representatives of Massachusetts-Bay, to be rescinded also; and the Houses of Representatives in other colonies refusing to comply Assemblies were dissolved.

These mandates spoke a language, to which the ears of English subjects had for several generations been strangers. The nature of assemblies implies a power and right of deliberation; but these commands, proscribing the exercise of judgment on the propriety of the requisitions made, left to the Assemblies only the election between dictated submission and the threatened punishment: A punishment too, founded on no other act, than such as is deemed innocent even in slaves–of agreeing in petitions for redress of grievances, that equally affect all.

The hostile and unjustifiable invasion of the town of Boston soon followed these events in the same year; though that town, the province in which it is situated, and all the colonies, from abhorrence of a contest with their parent state, permitted the execution even of those statutes, against which they so unanimously were complaining, remonstrating and supplicating.

Administration, determined to subdue a spirit of freedom, which English Ministers should have rejoiced to cherish, entered into a monopolizing combination with the East-India company, to send to this continent vast quantities of Tea, an article on which a duty was laid by a statute, that, in a particular manner, attacked the liberties of America, and which therefore the inhabitants of these colonies had resolved not to import. The cargo sent to South-Carolina was stored, and not allowed to be sold. Those sent to Philadelphia and New York were not permitted to be landed. That sent to Boston was destroyed, because Governor Hutchinson would not suffer it to be returned.

On the intelligence of these transactions arriving in Great Britain, the public spirited town last mentioned was singled out for destruction, and it was determined, the province it belongs to should partake of its fate. In the last session of parliament therefore were passed the acts for shutting up the port of Boston, indemnifying the murderers of the inhabitants of Massachusetts-Bay, and changing their chartered constitution of government. To enforce these acts, that province is again invaded by a fleet and army.

To mention these outrageous proceedings, is sufficient to explain them. For tho’ it is pretended, that the province of Massachusetts-Bay, has been particularly disrespectful to Great-Britain, yet in truth the behavior of the people, in other colonies, has been an equal “opposition to the power assumed by parliament.” No step however has been taken against any of the rest. This artful conduct conceals several designs. It is expected that the province of Massachusetts-Bay will be irritated into some violent action, that may displease the rest of the continent, or that may induce the people of Great-Britain to approve the meditated vengeance of an imprudent and exasperated ministry.

If the unexampled pacific temper of that province shall disappoint this part of the plan, it is hoped the other colonies will be so far intimidated as to desert their brethren, suffering in a common cause, and that thus disunited all may be subdued.

To promote these designs, another measure has been pursued. In the session of parliament last mentioned, an act was passed, for changing the government of Quebec, by which act the Roman Catholic religion, instead of being tolerated, as stipulated by the treaty of peace, is established; and the people there deprived of a right to an assembly, trials by jury and the English laws in civil cases abolished, and instead thereof, the French laws established, in direct violation of his Majesty’s promise by his royal proclamation, under the faith of which many English subjects settled in that province: and the limits of that province are extended so as to comprehend those vast regions, that lie adjoining to the northernly and westernly boundaries of these colonies.

The authors of this arbitrary arrangement flatter themselves, that the inhabitants, deprived of liberty, and artfully provoked against those of another religion, will be proper instruments for assisting in the oppression of such, as differ from them in modes of government and faith.

From the detail of facts herein before recited, as well as from authentic intelligence received, it is clear beyond a doubt, that a resolution is formed, and is now carrying into execution, to extinguish the freedom of these colonies, by subjecting them to a despotic government.

At this unhappy period, we have been authorized and directed to meet and consult together for the welfare of our common country. We accepted the important trust with diffidence, but have endeavored to discharge it with integrity. Though the state of these colonies would certainly justify other measures than we have advised, yet weighty reasons determined us to prefer those which we have adopted. In the first place, it appeared to us a conduct becoming the character, these colonies have ever sustained, to perform, even in the midst of the unnatural distresses and imminent dangers that surround them, every act of loyalty; and therefore, we were induced to offer once more to his Majesty the petitions of his faithful and oppressed subjects in America. Secondly, regarding with the tender affection, which we knew to be so universal among our countrymen, the people of the kingdom, from which we derive our original,1 we could not forbear to regulate our steps by an expectation of receiving full conviction, that the colonists are equally dear to them. Between these provinces and that body, subsists the social band, which we ardently wish may never be dissolved, and which cannot be dissolved, until their minds shall become indisputably hostile, or their inattention shall permit those who are thus hostile to persist in prosecuting with the powers of the realm the destructive measures already operating against the colonists; and in either case, shall reduce the latter to such a situation, that they shall be compelled to renounce every regard, but that of self-preservation. Notwithstanding the vehemence1 with which affairs have been impelled, they have not yet reached that fatal point. We do not incline to accelerate their motion, already alarmingly rapid; we have chosen a method of opposition, that does not preclude a hearty reconciliation with our fellow-citizens on the other side of the Atlantic. We deeply deplore the urgent necessity that presses us to an immediate interruption of commerce, that may prove injurious to them. We trust they will acquit us of any unkind intentions towards them, by reflecting, that we subject ourselves to similar inconveniences;2 that we are driven by the hands of violence into unexperienced and unexpected public convulsions, and that we are contending for freedom, so often contended for by our ancestors.

The people of England will soon have an opportunity of declaring their sentiments concerning our cause. In their piety, generosity, and good sense, we repose high confidence; and cannot, upon a review of past events, be persuaded that they, the defenders of true religion, and the assertors of the rights of mankind, will take part against their affectionate protestant brethren in the colonies, in favor of our open and their own secret enemies; whose intrigues, for several years past, have been wholly exercised in sapping the foundations of civil and religious liberty.

Another reason, that engaged us to prefer the commercial mode of opposition, arose from an assurance, that the mode will prove efficacious, if it be persisted in with fidelity and virtue; and that your conduct will be influenced by these laudable principles, cannot be questioned. Your own salvation, and that of your posterity, now depends upon yourselves. You have already shown that you entertain a proper sense of the blessings you are striving to retain. Against the temporary inconveniences you may suffer from a stoppage of trade, you will weigh in the opposite balance, the endless miseries you and your descendants must endure from an established arbitrary power. You will not forget the honor of your country, that must from your behavior take its title in the estimation of the world, to glory, or to shame; and you will, with the deepest attention, reflect, that if the peaceable mode of opposition recommended by us, be broken and rendered ineffectual, as your cruel and haughty ministerial enemies, from a contemptuous opinion of your firmness, insolently predict will be the case, you must inevitably be reduced to choose, either a more dangerous contest, or a final, ruinous, and infamous submission.

Motives thus cogent, arising from the emergency of your unhappy condition, must excite your utmost diligence and zeal, to give all possible strength and energy to the pacific measures calculated for your relief: But we think ourselves bound in duty to observe to you that the schemes agitated against these colonies have been so conducted, as to render it prudent, that you should extend your views to the most mournful events, and be in all respects prepared for every contingency. Above all things we earnestly intreat you, with devotion of spirit, penitence of heart, and amendment of life, to humble your-selves, and implore the favor of almighty God: and we fervently beseech his divine goodness, to take you into his gracious protection.

Ordered, That the Address to the people of Great Britain and the memorial to the inhabitants of the British colonies be immediately committed to the press & that no more than one hundred and twenty copies of each be struck off without further orders from the Congress.

Resolved, That an Address be prepared to the people of Quebec, and letters to the colonies of St. John’s, Nova-Scotia, Georgia, east and West Florida, who have not deputies to represent them in this Congress.

Ordered, That Thomas Cushing, Richard Henry Lee, and John Dickinson, be a committee to prepare the above address and letters.

Ordered, That Joseph Galloway, Thomas McKean, John Adams & William Hooper be a committee to revise the minutes of the Congress.

Ordered, that John Dickinson be added to the committee to Address the King.

Adjourned until tomorrow.

Edited with commentary by Gordon Lloyd.

Journals of the Continental Congress

Journals of the Continental Congress