Act II, Introduction: Second Continental Congress

Second Continental Congress, First Session

The First Continental Congress ended on a note of cautious optimism. King and Parliament had been informed that there were certain acts of Parliament enumerated in the Articles of Association of 1774 that needed to be repealed by September 10th, 1775 and that Congress would wait for a response, hopefully favorable. The delegates agreed to meet again in May 1775 just in case the response was not forthcoming in a timely manner or was unfavorable. No word from Britain had been received when forty-eight delegates from eleven colonies met again on May 10th, 1775.

There were familiar faces from the First Continental Congress: the Adams’s from Massachusetts, Roger Sherman from Connecticut, John Rutledge from South Carolina, the identical three-member Delaware and Connecticut delegations, and George Washington, Richard Henry Lee, and Richard Bland from Virginia. And there were the new faces of John Hancock from Massachusetts and Benjamin Franklin from Pennsylvania. Influential “moderate” delegates from the First Continental Congress such as John Jay from New York and Joseph Galloway from Pennsylvania were absent. But then neither was the “radical” Patrick Henry of Virginia. Thomas Jefferson arrived on June 21st.

On May 11th, Congress adopts a secrecy rule. Nevertheless, Congress from time to time, authorizes the publication of important decisions and resolutions. Congress, on May 15th, creates its first Committee with specific instructions: provide for the defense of New York without jeopardizing reconciliation with Britain. George Washington and Samuel Adams are members of that Committee. The “Accommodation” proposal on taxation offered by the British Parliament is rejected on May 26th, and a “Letter to the Oppressed Inhabitants of Canada” is adopted on May 29th.

On June 3rd, Congress creates seven Committees to address twin, and increasingly unrealizable, objectives: the common defense of the continent and reconciliation with Britain. “A day of humiliation, fasting, and prayer” to take place on July 20th is approved on June 7th and 12th, and a Five Member Committee is created to draft Rules and Regulations for the Army on June 14th. George Washington is elected Commander-in-Chief and Congress supports the General “with their lives and fortunes.” Benjamin Franklin writes on June 27th to a friend in Britain: “We shall give you one opportunity more of recovering our affections and retaining the connection; and I fear it will be the last.” And on June 30th, Congress passes 69 Rules and Regulations of War.

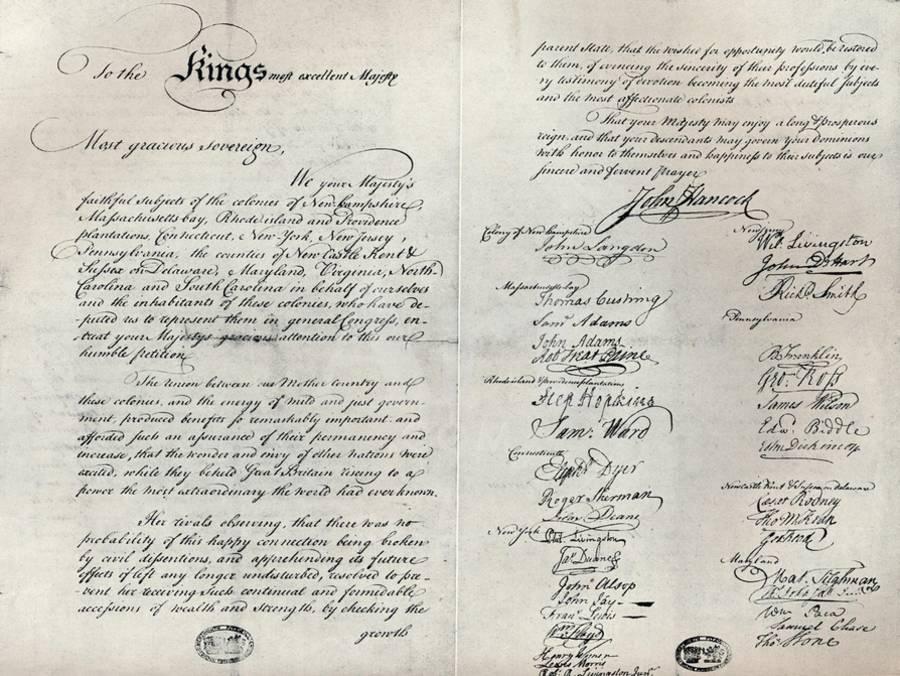

Congress passes The Three-Part Olive Branch Petition on July 5th, 1775, and during the next two weeks approves a “Declaration on the Causes and Necessity of Taking Up Arms,” an “Address to the People of Great Britain,” a “Speech to the Indians of the Six Confederate Nations,” and yet another moderate “Petition to the King” signed by 59 delegates.

On July 21st, Benjamin Franklin introduces Thirteen Articles of Confederation in an effort to provide a governmental structure for the continent. During the last week of July, Congress approves “an Address” to the people of Jamaica and Ireland. Apparently, the concept of the “Continent” spreads beyond Canada and includes the Caribbean, Bermuda, and Ireland! On July 22nd, a Four Member Committee is created to report on Lord North’s February 1775 Motion of Reconciliation. Interestingly, these four delegates—Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, and Roger Sherman—are elected to the Five Member Committee to draft the Declaration of Independence eleven months later.

Time for a break from talk of reconciliation, war, expansion, and independence. On August 1st, Congress adjourns, but they set a date to resume: September 5th. The message is: don’t act too precipitously because the King and Parliament may respond favorably to the petition for a redress of grievances. But be prepared for the worst, namely a rejection of the petition without the possibility of reconciliation.

Second Continental Congress, Second Session

Congress was scheduled to meet on September 5th, but failed to meet the quorum requirement until September 13th.

Letters, more Letters; Committees, more Committees; Reports, more Reports; Debates, more Debates; Claims, more Claims; even more Committees and more Resolutions. Prepare for War? Yes. Consider Reconciliation? Yes. Move toward Independence? Yes. The interplay of events and ideas influences the session: 1) British war actions in Massachusetts, New York, and the South, 2) King and Parliamentary words and deeds, 3) pamphlets and memorials, 4) changes in the delegations and their instructions, 5) twelve-hour working days, 6) numerous concerns over “the state of trade,” 7) setbacks in Canada and mixed relations with the Indian Tribes, 8) the absence of effective government based on consent at both the local and continental levels, 9) boundary disputes between the colonies, and 10) a strong desire to return home to friends and family eventually. These gradually turn Congress in the direction of Independence. There are, to quote John Adams, “many Circumstances” at work. “We must learn patience.” Patience is the central feature of this session as the Continental Congress wrestles with the transition from petition to declaration.

On November 1st, The King’s Speech and Parliamentary Proclamations of August 1775 arrive in America. Delegate Samuel Ward from Rhode Island wrote to his wife: “we are declared to be Rebels…this has a most happy Effect here for those who hoped for Redress from our Petitions now give them up & heartily join with us in carrying on the War vigorously.” Ward was optimistic. In a November 2nd letter, he writes that doubt and confusion over whether to reconcile or seek independence are gone and that we are all “Brother Rebels.”

But, Ward to the contrary, it is still not over yet. On December 5th, John Dickinson of Pennsylvania summarizes the history of the Petition-Reconciliation-Independence debate. And the debate continues. On December 6th, Congress agrees with the Committee of Proclamations that Americans are not rebels; rather they are exercising “the right to resist,” which is part of the British legal tradition. One step forward, one step back, and two from side to side.

Second Continental Congress, Third Session

The Third Session began on January 1, 1776. New members are selected, and some replaced. John Adams is reelected. Once again, Letters, more Letters; Committees, more Committees; Reports, more Reports; Debates, more Debates; Claims, more Claims; even more Committees and more Resolutions. What is new is the publication of Thomas Paine’s Common Sense, the presence of war on the continent, and unsettling news from Canada.

Congress requests a compilation of every Petition made to King and Parliament since 1762. New York is hesitant. “We desire Reconciliation,” says John Jay and James Duane adds that he is “not without some Hopes of Just and honorable peace.” Samuel Adams, on the contrary, thinks the King’s Speech of October 26, 1775, that arrived in Philadelphia on January 8, 1776, provides sufficient grounds to appeal to the laws of nature and seek independence. On February 13, James Wilson presents his “Draft of an Address to the Inhabitants of these Colonies,” the main point of which is to deny that America is in rebellion and thus no longer “dependent” on The King. Still, his first wish is “that America may be free.” John Penn and Robert R. Livingston concur in wanting a reconciliation. They want between BOTH freedom for America AND dependence on the King. Thomas Nelson of Virginia thinks that the majority of Congress are not yet ready to declare independence.

John Adams is thoroughly frustrated and decides it is time for a decision to go forward and not turn back. On February 17, he notes that his “measure of opening the ports, etc., labored exceedingly, because it was considered as a bold step to independence.” His effort was supported by Robert Alexander of Maryland. He is “almost convinced the Measure is right and can be justified by Necessity.” By the end of February, there is an even division of opinion in Congress over whether to keep seeking reconciliation or to pursue independence.

But the Adams’s have to endure another four months of frustration. On April 2, for example, John Adams laments that despite all the evidence, the situation continues to waver between “Hawk and Buzzard.” When will the delegates finally stop dithering about whether to 1) blame the King OR Parliament, and how long will they 2) wait for Commissioners with new proposals of Reconciliation? Yet, he wants the delegates to see for themselves that 1) Independence from both King AND Parliament is critical and 2) the Commissioners will offer nothing but more slavery. In mid-April, Samuel Adams expresses his own frustration with the dithering of the “Moderate Whigs.” The New York, Pennsylvania, Maryland, and South Carolina delegations remain divided over Reconciliation or Independence. The turning away from the dithering over Reconciliation or Independence occurred on June 8 when Congress approves a motion that a serious conversation take place over Independence and its consequences. The Journal does not provide the details of the conversation, but Thomas Jefferson recreates the debates from memory: there is no turning back.