Committee Assignments Chart and Commentary

TWELVE ACTION COMMITTEES

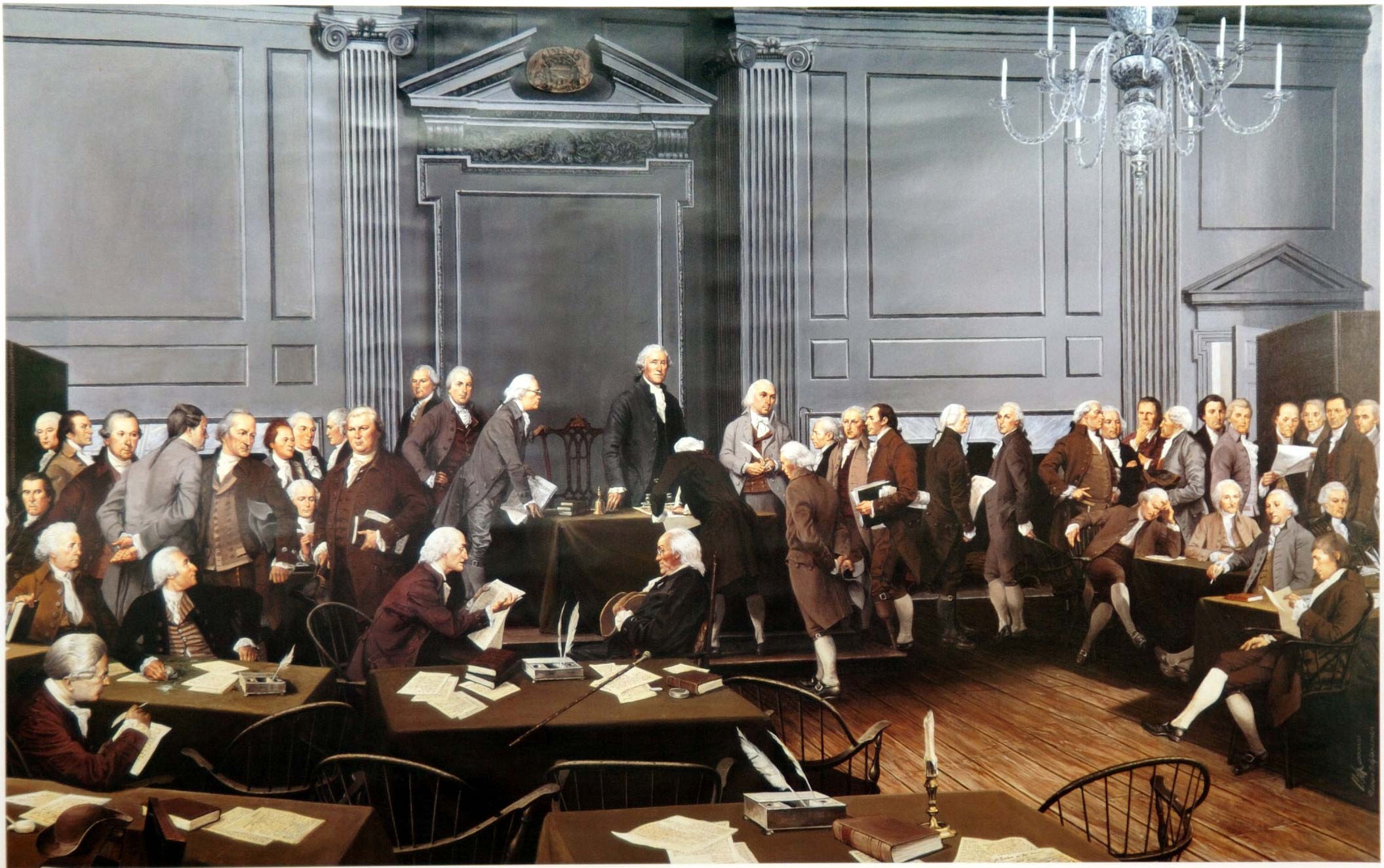

There are important moments in the life of a political gathering, such as an assembly of delegates, when recourse to a smaller number of the membership is necessary. The Constitutional Convention of 1787 found the need to resort to this on twelve different occasions during their four months. Each one of these twelve committees of the Convention is an “Action Committee,” in the sense that each one helps the Convention move to the next stage of the deliberative and decision-making process.

We suggest that it is useful to distinguish between two different kinds of action committees. The first is on behalf of the deliberative process and is an effort to set down the rules or secure a breakthrough so that deliberation can continue in a productive fashion. The second is on behalf of the decision-making process itself. In other words, the action involved is not primarily focused on keeping the deliberative process alive and well, but bringing the gathering toward making some decisions from which there is little possibility of reversal.

During the months of May, June, and July, the Convention sat as a Committee of the Whole. That meant that the entire membership was involved in the give and take together on essential questionssitting as a Committee of the Whole makes it far easier to explore, alter, and prodrather than the emphasis being on the delegates having to decide, once and for all as it were, on specific articles, sections, and clauses. The decision-making stage occurs during the months of August and September where the task of filling in the details and hammering out specific compromises are delegated to members of committees selected by the entire Convention. This is where the votes of the delegates become crucial to the outcome.

ACT ONE AND ACT TWO

Acts One and Two of the Four Act Drama capture the deliberative stage of the Convention. Accordingly, it is not surprising that out of the twelve committees listed, only four occur during this earlier phase of the Convention: the Rules Committee and the three Committees of Representation, which can be collapsed into the “Gerry Committee.” So we actually have only two important committees to examine in this stage of the conversation.

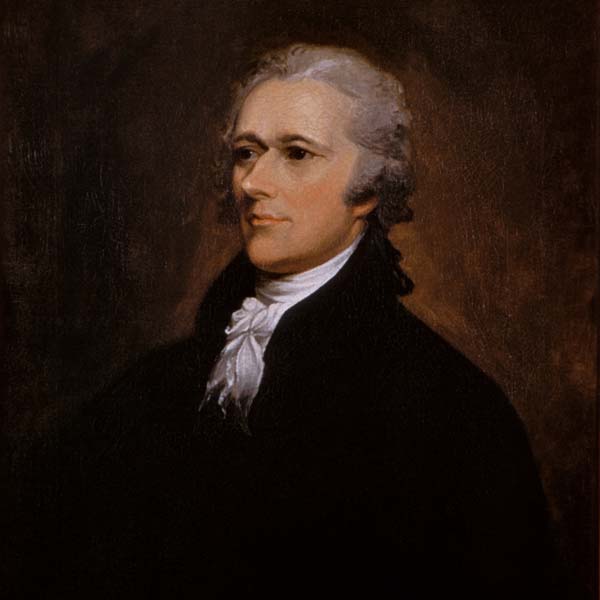

The three member Rules Committee, under the leadership of the Virginia legal scholar, George Wythe, laid down rules for what they considered to be a civilized conversation. Hamilton and Charles Pinckney—later accused of being a monarchist and aristocrat respectively—joined Wythe in proposing rules aimed to foster open deliberation among the delegates. One of the more controversial recommendations was the rule of secrecy. Madison, both at the time of the Convention and later, vigorously defended this rule; he thought it encouraged the free exchange of ideas among the members so vital for the success of the deliberative process. The secrecy rule has been criticized by influential Progressive Historians of the twentieth century who portray it as evidence of an upper class and reactionary disposition at the Convention to undermine the democratic spirit of the Revolution of 1776.

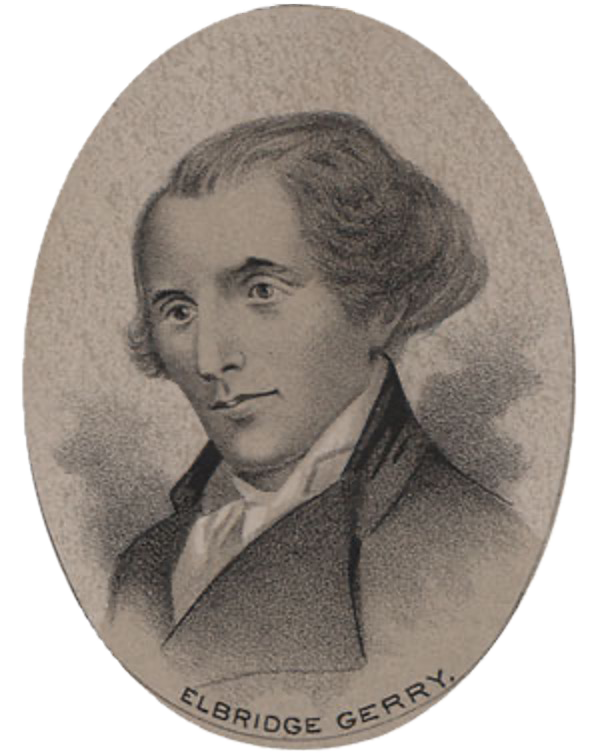

The membership of the Gerry Committee provides a crucial insight into the mood of the Convention at the end of June and the beginning of July. At the end of Act One, the wholly national Virginia Plan, albeit slightly amended, was on the table for further consideration. But the opposition, led by Sherman and Ellsworth of Connecticut, insisted on a compromise between the wholly national Virginia Plan and the wholly federal New Jersey Plan introduced by William Paterson of New Jersey. Or if no compromise were possible, then they favored the adoption of the federal New Jersey Plan.

The last two weeks of June marks the low point of the Convention. Conversation and deliberation had given way to threats of secession, lines were drawn in the sand, and frustration ran high. At the end of June, Oliver Ellsworth tried one more time to break the deadlock with his partly national-partly federal proposal. This time it worked, and the more pragmatic delegates decided to create a committee to move the deliberative process forward. The Convention, still sitting as a committee of the Whole, on July 2 elected 11 members—one from each State present—to seek a partly national-partly federal compromise.

But the Gerry Committee could not have made that recommendation, and made it stick, unless the members of the committee, and thus the Convention itself, were so inclined. Davie from North Carolina announced his support for the partly national and partly federal compromise in late June, as did Franklin, Luther Martin, Paterson, Sherman–Ellsworth, and Yates. The Convention could have chosen Madison rather than Mason from Virginia, Wilson rather than Franklin from Pennsylvania, and King rather than Gerry from Massachusetts, but the delegates did not. The 11 members chosen by the entire body of delegates were selected because of their inclination to seek a compromise; the members of the Gerry Committee were those representatives from each state that could be relied upon to propose and secure the passage of the Connecticut Compromise on July 16.

ACT THREE AND ACT FOUR

8 of the 12 committees met during Act Three and Act Four, and four of these committees were crucial in the framing of the Constitution: The Committee of Detail, the Committee of Slave Trade, the Brearly Committee, and the Committee of Style. Of the other four, the Committee of Trade was actually a companion to the Slave Trade Committee and worked out the final North South compromise on navigation issues. Two other committees dealt with existing state debts and state commitments under the new Constitution. The eighth committee on “economy, frugality, and manufactures” was created during the last week of the Convention and never filed a report.

The 5 members of the Committee of Detail—Rutledge (chair), Ellsworth, Gorham, Edmund J. Randolph, and Wilson—were chosen by the entire Convention to turn the various proposals and recommendations made in Act One and Act Two into the first draft of the Constitution. They met for nearly two weeks and produced the Committee of Detail Report that became the focus of conversation of the entire Convention during August. It is beyond the scope of this commentary to speculate on the twists and turns that must have taken place among the delegates over that period. Or even why these five were chosen. Suffice it to note, that Rutledge managed to secure a strong pro-slave trade provision, Edmund J. Randolph, by his subsequent actions, must have been insistent upon the money bills provision of the The Connecticut Compromise, Ellsworth was there to secure the structural importance and reserved powers of the states, and Wilson and King probably urged the inclusion of as much high-toned government as possible in the elevation of the Senate to a central player. Interestingly, the Committee agreed that the powers of Congress be enumerated—this is where the interstate and international commerce clause and the necessary and proper clause make their appearance—but the structure and powers of the Executive branch are still in an inconclusive situation.

I suggest that once the Convention shifted from an emphasis on committees of deliberation to an emphasis on committees of decision-making, then the work of the committees takes on a privileged position. Accordingly, the delegates reviewing and debating the work of the committees are probably likely to challenge the recommendations of the committee only when something big is at stake. Thus, we should pay close attention to important concerns generated by the Committee of Detail Report.

There were two major concerns that attracted the attention of the delegates. The provision in the Report that banned Congress from ever regulating (international commerce just granted in) the slave trade generated considerable division near the end of August. The Slave Trade Committee, also known as the Livingston Committee, was created to find a “middle ground” between the Committee of Detail Report that guaranteed the permanent existence of the international slave trade and those delegates who wished to limit the slave trade in the foreseeable future. This committee recommended that Congress be released from this restriction in 1800. Anti-slave trade delegates Madison, L. Martin, King, and John Dickinson were members of the Committee of the 11 elected by the entire Convention. The final decision of the Convention was to release the Congressional prohibition in 1808.

The delegates were also concerned about “left overs,” especially the Presidency. The Brearly Committee that included Madison, King, G. Morris, Dickinson and Sherman settled on the Electoral College as the compromise mode of electing the President. And in the process they elevated the Executive to a position of importance in the separation of powers system.

The Convention, in mid-September, also elected five members to the Committee of Style: Hamilton, William Samuel Johnson (Chairman), King, Madison, and G. Morris. With the possible exception of William Samuel Johnson, the members were very warm supporters of the original Virginia Plan that proposed a wholly national remedy for the ills of republicanism and defended time and again any possible move for a higher toned government.

The mood of the Convention had shifted once again, but this time, in September, it had shifted back toward the supporters of the original Virginia Plan. This is revealed by the election of Madison, King, and G. Morris to the Brearly Committee and the Committee of Style. It’s almost like the delegates at the Convention let the initial promoters of the national movement have the last say after the Sherman opposition had their say in July and August.

A Rules Committee (created May 25, delivered report on May 28) 3 members

B First Committee of Representation (created July 2, also known as the “Gerry Committee”) 11 members

C Second Committee of Representation (created July 6, also known as “the Committee of Five”) 5 members

D Third Committee of Representation (created July 9) 11 members

E Committee of Detail (created July 24, report delivered on August 6 and discussed throughout August) 5 members

F Committee of Assumption of State Debts (created August 18) 11 members

G Committee of Slave Trade (created Aug. 22, also known as “the Livingston Committee,” delivered report on Aug. 24) 11 members

H Committee of Trade (created August 25) 11 members

I Committee of State Commitments (created August 29) 11 members

J Committee of Leftovers (created August 31, also known as the “Brearly Committee”) 11 members

K Committee of Style (created Sept. 10, report delivered on Sept. 12 and discussed during the remainder of the Convention) 5 members

L Committee of Economy, Frugality and Manufactures (created September 13) 5 members

| Name | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L |

| Gilman, NH (1) | ♦ | |||||||||||

| Langdon, NH (3) | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | |||||||||

| Gerry, MA (1) | ‡ | |||||||||||

| Gorham, MA (4) | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ||||||||

| King, MA (6) | ♦ | ‡ | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ||||||

| Strong, MA (0) | ||||||||||||

| Ellsworth, CT (1) | § | ♦ | ||||||||||

| Johnson, CT (4) | ♦ | ♦ | ‡ | ♦ | ||||||||

| Sherman, CT (5) | § | ♦ | ♦ | ‡ | ♦ | |||||||

| Hamilton, NY (2) | ♦ | ♦ | ||||||||||

| Lansing, NY (0) | ||||||||||||

| Yates, NY (2) | ♦ | ♦ | ||||||||||

| Clymer, PA (2) | ♦ | ♦ | ||||||||||

| Fitzsimons, PA (1) | ♦ | |||||||||||

| Franklin, PA (2) | ♦ | ♦ | ||||||||||

| Ingersoll, PA (0) | ||||||||||||

| Mifflin, PA (0) | ||||||||||||

| Morris, G., PA (4) | ‡ | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ||||||||

| Morris, R., PA (0) | ||||||||||||

| Wilson, PA (2) | ♦ | ♦ | ||||||||||

| Brearly, NJ (2) | ♦ | ‡ | ||||||||||

| Dayton, NJ (1) | ♦ | |||||||||||

| Houston, W.C., NJ (0) | ||||||||||||

| Livingston, NJ (3) | ‡ | ‡ | ♦ | |||||||||

| Paterson, NJ (1) | ♦ | |||||||||||

| Bassett, DE (0) | ||||||||||||

| Bedford, DE (1) | ♦ | |||||||||||

| Broom, DE (0) | ||||||||||||

| Dickinson, DE (4) | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ||||||||

| Read, DE (2) | ♦ | ♦ | ||||||||||

| Carroll, MD (3) | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | |||||||||

| Jenifer, MD (0) | ||||||||||||

| Martin, L., MD (2) | ♦ | ♦ | ||||||||||

| McHenry, MD (1) | ♦ | |||||||||||

| Mercer, MD (0) | ||||||||||||

| Blair, VA (0) | ||||||||||||

| Madison, VA (4) | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ||||||||

| Mason, VA (4) | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ‡ | ||||||||

| McClurg, VA (0) | ||||||||||||

| Randolph, VA (3) | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | |||||||||

| Washington, VA (0) | ||||||||||||

| Wythe, VA (1) | ‡ | |||||||||||

| Blount, NC (0) | ||||||||||||

| Davie, NC (1) | ♦ | |||||||||||

| Martin, A., NC (0) | ||||||||||||

| Spaight, NC (0) | ||||||||||||

| Williamson, NC (5) | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | |||||||

| Butler, SC (2) | ♦ | ♦ | ||||||||||

| Pinckeny, C., SC (1) | ♦ | |||||||||||

| Pinckney, C.C., SC (2) | ♦ | ♦ | ||||||||||

| Rutledge, SC (5) | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ‡ | ‡ | |||||||

| Baldwin, GA (4) | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ||||||||

| Few, GA (1) | ♦ | |||||||||||

| Houstoun, GA (1) | ♦ | |||||||||||

| Pierce, GA (0) | ||||||||||||

♦ — Member of Committee

‡ — Chairman of Committee

§ — Ellsworth was “indisposed;” Sherman substituted.