The Contributions of the Antifederalists

Why the Name Antifederalist?

Who were the Antifederalists and what did they stand for? The name, Antifederalists, captures both an attachment to certain political principles as well as standing in favor and against trends that were appearing in late 18th century America. It will help in our understanding of who the Antifederalists were to know that in 1787, the word “federal” had two meanings. One was universal, or based in principle, and the other was particular and specific to the American situation.

The first meaning of “federal” stood for a set of governmental principles that was understood over the centuries to be in opposition to national or consolidated principles. Thus the Articles of Confederation was understood to be a federal arrangement: Congress was limited to powers expressly granted, the states qua states were represented equally regardless of the size of their population, and the amending of the document required the unanimous consent of the state legislatures. A national or consolidated arrangement by contrast suggested a considerable relaxing of the constraints on what the union could and could not do along with a conscious diminution in the centrality of the states in the structure of the arrangement as well as the alteration of the binding document.

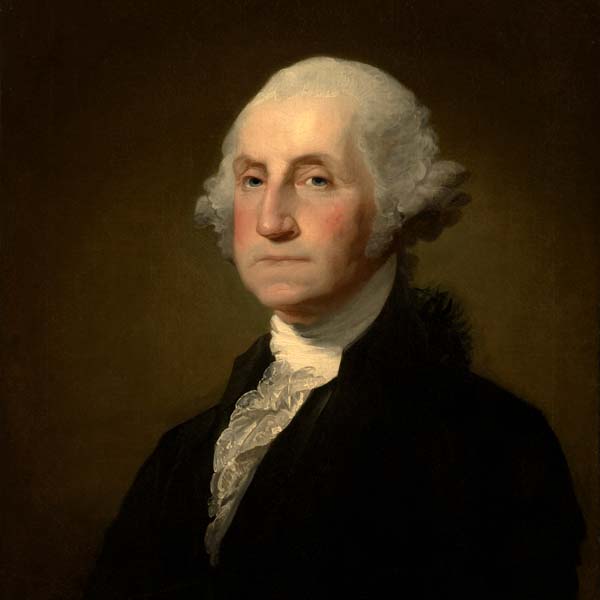

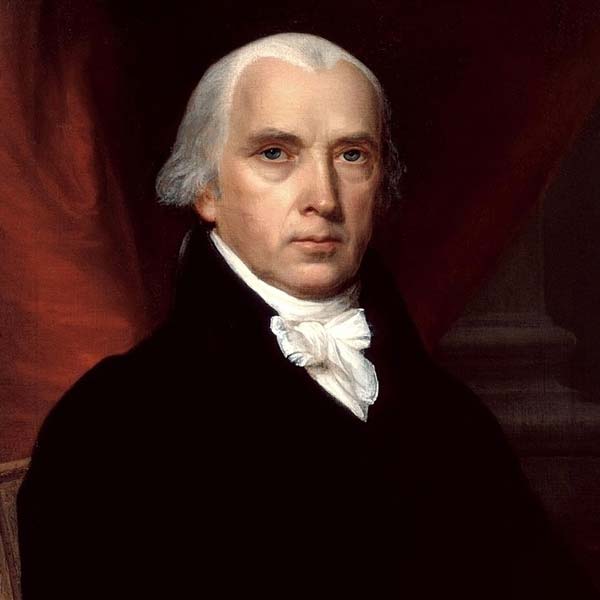

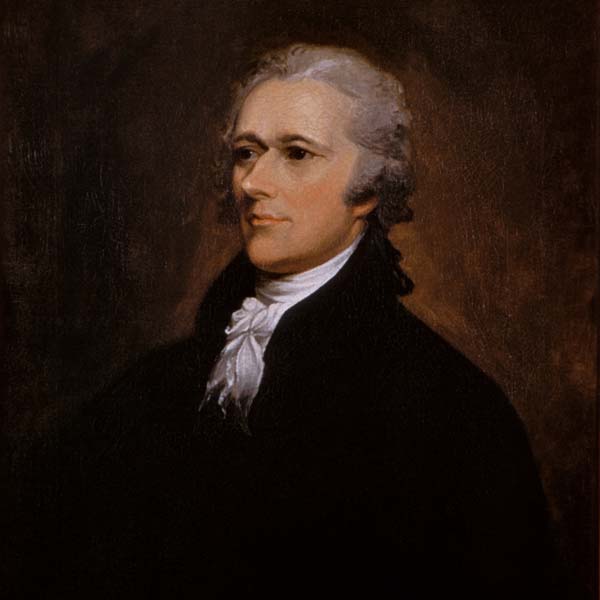

The second meaning of “federal” had a particular American character. In the 1780s, those folks who wanted a firmer and more connected union became known as federal men. People like George Washington, Gouverneur Morris, James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, and James Wilson were known as federal men who wanted a firmer federal, or even national, union. And those people like Patrick Henry, Richard Henry Lee, George Clinton, Melancton Smith, and Roger Sherman, who opposed or who raised doubts about the merits of a firmer and more energetic union acquired the name of antifederal men who opposed an inclination to strengthen the ties of Union with a focus on centralized direction.

In the rough and tumble of American politics, the name by which one is known is often not of one’s own doing. The Antifederalists would have preferred to be known as democratic republicans or federal republicans, but they acquired the name antifederal, or Anti-federal, or Antifederal as a result of the particular events of American history. If we turn to principles to define what they stood for, the content of their position was what was known in history as an attachment to federal principles: a commitment to local government and limited general government, frequent elections and rotation in office, and to writing things down because our liberties are safer as a result.

Put differently, the actual name “Antifederalists” did not exist before 1782. It is a 1780s American contribution to the enduring American issue of what should government do, which level of government should do it, and which branch of which level should do it. This “problem in nomenclature” has led scholars over the ages to suggest, we think unfortunately, that the pro-constitutional nationalists, like Madison and Hamilton, actually consciously “stole” the name Federalist for propaganda purposes to improve their chances of persuading the electorate and the delegates to the ratifying conventions to adopt the Constitution. Rhetoric, both on behalf of, and in restraint of, the role of the federal government, is built into the very fabric of the American system. And the controversy over the name “Antifederalist” reflects that inherent quarrel.

MATCHING UP THE ANTIFEDERALIST ESSAYS WITH THE FEDERALIST ESSAYS

There were no three Antifederalists who got together in New York, or Richmond, and said, “Let’s write 85 essays in which we argue that the Constitution should be either rejected or modified before adoption.” Thus, in contrast to the pro-Constitution advocates, there is no one book—like The Federalist (Papers)—to which the modern reader can turn to and say, “Here’s The Antifederalist (Papers).” Their work is vast and varied and, for the most part, uncoordinated.

There is thus a sense in which The Federalist makes our understanding of the American Founding relatively easy: here is the one place to go to get the authoritative account of the Constitution. One purpose of this website is to recover the arguments of the opposition. This recovery is based on a) a conversation that took place over several years and in which no blood was spilled, and b) the views of the Antifederalists, which are deeply embodied in the Constitution and the American tradition. The Antifederalists, as we argue in the section on the Antifederalist Legacy, are still very much alive and well in 21st century America.

An attempt to create an imaginary The Antifederalist Papers, to put along side The Federalist Papers for comparison purposes, is actually doing two contrary things: a) creating an impression that this specific Federalist paper matches up with that specific Antifederalist paper and b) capturing the worthwhile and accurate fact that a conversation of vital importance took place and both sides did address the concerns of the other side. The Timeline encourages the reader to see the following interplay: the pro-constitutional Caesar essays were responded to by the Antifederalist Brutus and Cato essays and these in turn were responded to with the launching of the essays by Publius that became The Federalist Papers in 1788. And this sort of interplay continues throughout the ratification process.

In certain places, as we show in this comparison of debate topics, one can certainly match up several Antifederalist essays with essential essays in The Federalist. The Antifederalists, as Herbert Storing has correctly suggested, criticized the Constitution and The Federalist criticized the Antifederalists. It makes sense, on the whole, however, to argue that the conversation took place at the founding at a thematic level rather than try to portray a conversation that took place at an individual specific essay-by-specific-essay level.

The Antifederalists were active in their opposition to the adoption of the Constitution even before the signing on September 17, 1787. And by November and December, they were actually winning the out-of-doors debate at least in terms of the sheer number of newspapers who carried their message in the key states of Massachusetts, New York, and Virginia. And if we take a look at the Six Stages of Ratification, we can see the impact of their pamphlet war on the selection of the delegates in these three key states.

THREE KINDS OF ANTIFEDERALISTS

There are three kinds of Antifederalists, but each voice is an important one in the creation and adoption of the Constitution and the subsequent unfolding of American politics.

The first kind is represented by politicians such as Roger Sherman and Oliver Ellsworth of Connecticut. They entered the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia with a suspicious disposition toward the Virginia Plan and its attempt to give sweeping powers to Congress and to reduce the role of the states in the new American system. This first group achieved considerable success in modifying this national plan back in the direction of federal principles. Thus, in the final document, the powers of Congress are listed, each state is represented equally in the Senate and composed of Senators elected by the state legislatures, the president is to be elected by a majority of the people plus a majority of the states, the Constitution is to be ratified by the people of nine states, and the Constitution is to amended by 2/3 of the House plus 2/3 of the Senate plus 3/4 of the state legislatures. Put differently, Sherman and Ellsworth secured the federal principles in the very Constitution itself and thus the Constitution is actually partly national and partly federal. In the end, Sherman and Ellsworth supported the adoption of the Constitution and thus secured the presence of the Antifederalist position in the American tradition.

The second kind of Antifederalist is one who was not privy to the debate in Philadelphia, and has some deep concerns about the POTENTIALITY of the Constitution to lead to the concentration of power in the new government. We are talking about people such as Melancton Smith, Abraham Yates (Brutus), and George Clinton in New York, Richard Henry Lee (Federal Farmer) in Virginia, Samuel Bryant (Centinel) in Pennsylvania, and John Winthrop (Agrippa) in Massachusetts. They warned that without certain amendments, including a bill of rights that stated clearly what the new government could and could not do, the new Constitution had the POTENTIALITY to generate a consolidated government over a large territory in which one of the branches of government—the Presidency and the Judiciary were the leading candidates—would come to dominate. They warned that the partly national and partly federal Constitution would veer naturally in the direction of wholly national unless certain precautions were put in place to secure the partly-national and partly-federal arrangement. These Antifederalists are the ones we have included in our selection of the Essential Antifederalists on this website. Although we have to knit together their position from a number of sources, and although the Constitution was unconditionally ratified, their views entered the amended Constitution by way of James Madison and the First Congress.

The third and final group of Antifederalists was those who wanted as little deviation from the Articles as possible and saw the partly-national and partly-federal compromise as totally unsustainable. The arrangement was doomed to produce a wholly national outcome unless radical amendments were secured that altered and abolished the very structure and powers that the Framers took four months to erect. Ratifying delegates like Patrick Henry come to mind; he deliberately made a nuisance of himself at the Virginia Ratifying Convention disrupting the orderly process of debates at will. George Mason and Elbridge Gerry also come to mind. They started off as warm supporters of a stronger national government but within twelve months had become open opponents of even the friendly amendments proposed by the second type of Antifederalist. Within this third type of Antifederalist, we would also include Philadelphia delegates Luther Martin, John Lansing, Robert Yates, and John Mercer. We have not included them in the Essential Antifederalist listings. Their legacy, as we have tried to capture in The Antifederalist Legacy, is probably to be found in the Calhoun movement in favor of secession from the American founding.

So I would argue, in the spirit of Thomas Jefferson and George Washington, that while The Federalist Papers are among the best essays ever written on representative government, they would not be as good as they are, or as many essays as there are, if it were not for the persistent critique of the Antifederalists who helped define the American conversation over what should government do, which level of government should do it, and which branch of that level of government should do it. Those questions are what the Essential Antifederalists bring to the conversation.

THE FOUR OPTIONS OF ANTIFEDERALISM

It is helpful to consider four options when reflecting on the importance of the Antifederalists. They are 1) incoherent and irrelevant, 2) coherent and irrelevant, 3) incoherent and relevant, and 4) coherent and relevant. And which option we choose is in large part linked to a) how we define the Antifederalist project, b) how we interpret The Federalist and c) whether or not we are willing to retrieve the Antifederalists on their own terms or whether we see them as valuable in a quarrel over the American regime.

One way to define the Antifederalists is that they are those who opposed ratification of the unamended Constitution in 1787-1788. This definition might well make them lower case antifederalists or anti-federalists. The point is that they are both incoherent and irrelevant. A broader definition, one that reaches back to Montesquieu or to Aristotle introduces the possibility that they may be either coherent but irrelevant (Cecelia Kenyon) or incoherent but relevant (Herbert Storing). The upper case and hyphenated Anti-Federalist nomenclature is the preferred appellation for this approach. There is one last choice—the Antifederalists are coherent and relevant—and this suggests that we call them Antifederalists, upper case and non-hyphenated.

This fourth approach argues that their coherence and relevance is located in their basically American and new world character. They are neither Kenyon’s “men of little faith” nor Storing’s “incomplete reasoners,” and thus “junior founders.” Their thought is grounded in the American struggle for independence, draws strength from the colonial tradition, the natural rights tradition, and new state constitutions that emerged between 1776 and 1780. Their thought is moreover informed by the Articles of Confederation of the 1780s, matured by the debates over the creation and adoption of the Constitution, culminates with the adoption of the Bill of Rights and then bids farewell to its creative phase with the introduction of the Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions. I encourage the reader to consider this broader, and basically American and new world, definition of the Antifederalist project.

THE ANTIFEDERALIST REPUTATION

This reputation of the Antifederalists as irrelevant, even proto-Calhoun, disunionists was shaped, in part, by Alexander Hamilton‘s observation in Federalist 1: “we already hear it whispered in the private circles of those who oppose the new Constitution, that the thirteen States are of too great an extent for any general system, and that we must of necessity resort to separate confederacies of distinct portions of the whole.” The response by the Antifederalist, “Centinel,” to Hamilton has been largely ignored: this claim of disunion, he said, is “from the deranged brain of Publius, a New York writer, who has devoted much time, and wasted more paper in combating chimeras of his own creation.”

James Madison‘s commentary in Federalist 38 was no doubt also influential in portraying the Antifederalists as incoherent. Madison asks: “Are they agreed, are any two of them agreed, in their objections to the remedy proposed, or in the proper one to be substituted? Let them speak for themselves.” But Madison does not “let them speak for themselves.” When the Antifederalists are permitted to speak for themselves, as Antifederalist Melancton Smith demonstrates, a remarkably coherent alternative emerges. “An Old Whig” makes the same point: “about the same time, in very different parts of the continent, the very same objections have been made, and the very same alterations proposed by different writers, who I verily believe, know nothing at all of each other.” This appeared six weeks prior to Federalist 38. When the Antifederalists are permitted to speak for themselves, a coherent and relevant account emerges.

The Federalist argues for checks and balances, especially against the legislature; the Antifederalists support term limits and rotation in office for all elected and appointed officials. But this is why Kenyon calls them irrelevant; they held to a scheme of representation that was outmoded even for 1787. By contrast, The Federalist argues that the representative needs a longer duration in office than provided by traditional republicanism in order to exercise the responsibilities of the office and resist the narrow and misguided demands of an overbearing and unjust majority. Because the Antifederalists were dubious that one could be both democratic and national, they urged less independence for the elected representatives. They claimed that practical experience demonstrated that short terms in office, reinforced by term limits, would be an indispensable additional security to the objective of the election system to secure that the representatives were responsible to the people. For the Antifederalists, a responsible representative—the essential characteristic of republicanism—was constitutionally obliged to be responsive to the sovereign people. Ultimately, the “accountability” of the representative was secured by “rotation in office,” the vital principle of representative democracy. This is the concept of the citizen-politician who serves the public briefly and then returns to the private sphere.

In Federalist 23, Hamilton describes the Antifederalist position as “absurd” because they admit the legitimacy of the ends and then are squeamish, even, cowardly, about the means: “For the absurdity must continually stare us in the face of confiding to a government the direction of the most essential national interests, without daring to trust it to the authorities which are indispensable to their proper and efficient management. Let us not attempt to reconcile contradictions, but firmly embrace a rational alternative.” The Antifederalists, according to Hamilton, are mushy thinkers; they fuss over means rather than focusing on ends. Storing totally agrees: they should have focused on the ends of union and the (limited) role of the states in the accomplishment of those ends. The Antifederalists, according to Hamilton and Storing, wanted union but argued against giving the union the means to secure the ends. They were absurd and thus they were incoherent. But there is more. According to Storing, the Antifederalists also avoided the hard and “ugly truth” of Federalist 51: the people can’t govern themselves voluntarily. This truth, says Storing, is something that the Federalists faced squarely.

COHERENT AND RELEVANT

Perhaps that the Antifederalists have a coherent understanding of federalism and republicanism—grounded in “democratic federalism” and “constitutional republicanism”—and that this coherent understanding is worth keeping alive in the twenty-first century because it addresses what ails the contemporary American federal republic. Antifederalist thought is the built-in American antidote for the ills of the American federal republic. In particular, the three other alternative explanations either read history backwards or import European or ancient categories to explain an American experience.

The Antifederalists are not primarily interested in the “good government” project of The Federalist or the “best regime” project of the ancients, or the “exit rights” project of the secessionists or many of the other projects invented by the various historical schools; instead, I suggest they are interested in the creation and preservation of free government. They remind us that free government means limited government, and thus the political project should be focused on limiting rather than empowering politicians. Antifederalist statesmanship involves an attachment to means, rather than an administration of ends. There is nothing absurd or incoherent about being fussy over the use and misuse of means because means are actually powers and the abuse of powers sets us down the slippery slope to old world tyranny.

The Antifederalists speak to those who have become increasingly disillusioned by the collapse of decentralized state and local government, the greater intervention by the federal government in economic matters, the blurring of the separation of powers, and the replacement of voluntary associations by government programs. The Antifederalists warn: beware the dangers of “democratic nationalism,” and “delegated constitutionalism.” These are warnings from within the very American System itself. They warn us that there is something morally corrosive about the exercise of political power and thus they remind us about the need for the rule of law. And they warn about the dangers of the Federalist temptation with empire abroad. The Antifederalists are not isolationists, men of little faith, or junior partners; they are “Antitemptationalists” with a message of liberty and responsibility that resonates across the centuries.

“On the most important points,” then, the Antifederalists were not only in agreement but their position was coherent and is currently relevant. They believed that republican liberty was best preserved in small units where the people had an active and continuous part to play in government. Although they thought that the Articles best secured this concept of republicanism, they were willing to bestow more authority on the federal government as long as this didn’t undermine the principles of federalism and republicanism. They argued that the Constitution placed republicanism in danger because it undermined the pillars of small territorial size, frequent elections, short terms in office, and accountability to the people, and, at the same time, encouraged the representatives to become independent from the people and the state governments. They warned that unless restrictions were placed on the powers of Congress, the Executive, and the Judiciary, the potentiality for the abuse of power would become a reality. These warnings culminated in their insistence on a Bill of Rights which, in conjunction with small territory, representative dependency, and strict construction, they conceived as the ultimate “auxiliary precaution.”

The expression of discontent over the last fifty years about American politics has an ominous ring, revealing the widespread Antifederal mood in the electorate. Among the dramatic changes in recent American politics are the alarming alienation of the citizenry from the electoral system, the increased presence of the centralized Administrative State, and the dangerous consequences of an activist judiciary that openly thwarts the deliberate sense of the majority. These are all Antifederalist concerns about the tyranny of politicians. The term limits movement of the late twentieth century demonstrates that the Antifederalist message—keep your representatives on a short leash, otherwise you will lose your freedom—still resonates with the American people, because Antifederalism is very much part of the American political experience.

When we hear the claim that our representatives operate independently of the people, and that the Congress fails to represent the broad cross-section of interests in America, we are hearing an echo of the Antifederalist critique of representation. When we hear that the federal government has spawned a vast and irresponsive administrative bureaucracy that interferes too much with the life of American citizens, we are reminded of the warnings of the Antifederalists concerning consolidated government. They warn that, in effect, executive orders, executive privileges, and executive agreements will create the “Imperial Presidency.” And they warn that an activist judiciary will undermine the deliberate sense of the majority. The criticism that Americans have abandoned a concern for their religious heritage and neglected the importance of local customs, habits, and morals, recalls the Antifederalist dependence upon self-restraint and self-reliance. When we hear a concern for the passing of decentralization—old time federalism—we are hearing the Antifederalist lament.

The Antifederalist project calls for a rejuvenation of interest in Antifederalist “democratic federalism” and “constitutional republicanism.” Since American politics is often a debate over the possibilities and limitations of the separation of powers, an independent judiciary, federalism, and representative government, it is vital that the potency of Antifederalist political analysis be restored. If the electorate has “lost faith” in the responsibility of the representatives in every branch of government, then the very concept of representation undergirding the country is in crisis. What is the solution? If no one cares either about the question, or the solution, then America is perhaps doomed to go the way of previous great regimes, and the experiment in “republican government” is exactly what opponents through the centuries have predicted it would be: a complete failure thus proving that the human race is incapable of being governed other than by force and fraud.

Antifederalist political science advocated concentration of the power of the people and eliminating temptations for the concentration of power in officeholders. The heart of their method was to propose a scheme of representation that safeguarded interests and avoid the clashes of factions. This called for certain homogeneity of interests, as opposed to the Madisonian encouragement of diverse interests. The latter approach they rejected as unnecessary and dangerous. They placed their faith instead in the virtue of “middling” Americans—a virtue that was not informed by ancient Sparta or even ancient Rome but by the modern doctrine of personal self-reliance—coupled with holding their representatives “in the greatest responsibility to their constituents.”

The Antifederalists viewed the Constitution as creating mutually independent sovereign agents. They argued that such independent rulers would “erect an interest separate from the ruled,” which will tempt them to lose both their federal and their republican mores.

The Antifederalists concluded that unless executive power was yet more limited, representation more broadened, presidents and senators made more responsible to the people and the state governments protected—unless the arrangement was significantly modified—the proposed regime would necessarily destroy political liberty by destroying the sovereignty of the people, the litmus test of republicanism. As an expression of this “constitutional republicanism,” they insisted on a Bill of Rights as a declaration of popular sovereignty.

In conclusion, the Antifederalists warned about the tendency of the American system toward the consolidation of political power in a) the nation to the detriment of the various states, and b) one branch of the federal government at the expense of the separation of powers. They warned about c) the corrupting influence that political power has on even decent people, whom decent people elected into office, and d) that the rule of law has a privileged position in republican government. They also anticipated the idea that e) all politics is—or should be—local and thus particular attachments rather than abstract ideas matter in the preservation of a liberal political order.