Dimension III: The House Version

COMMENTARY

The House debated the Select Committee Report from August 13 through August 24. On August 3, Madison moved—no one else seemed interested in moving this project along—that the Select Committee Report be discussed by the whole House. Again, if it weren’t for Madison, the House would have shown no urgency in the First Session for considering a bill of rights. Fisher Ames was actually agitated by Madison’s insistence to consider a bill of rights. Writing to George R. Minot on August 12, 1789, Ames notes: “We are beginning the amendments in a committee of the whole. We have voted to take up the subject, in preference to the Judiciary, to incorporate them into the Constitution, and not to require, in committee, two thirds to a vote. This cost us the day. To-morrow we shall proceed. Some General, before engaging, said to his soldiers, ‘Think of your ancestors, and think of your posterity.’”

The discussion over the Bill of Rights was uninterrupted by other pressing business and unlike the preceding three months was irritable and even acrimonious. William L. Smith wrote to Edward Rutledge August 15, 1789: “There has been more ill-humor & rudeness displayed today than has existed since the meeting of Congress & to make it worse, the weather is intensely hot.” Similarly, Thomas Hartley to Jasper Yeates August 16, 1789: “We had Yesterday warm debates about amendments—and what is very curious the Antis do not want any at this Time—we are obliged in Fact to force them upon them. I am sorry that Business was brought forward this session—but we must pay attention to it for a Day or two more.” And George Leonard to Sylvanus Bourne August 16, 1789: “For three days past the proposed amendments have been under Consideration, the Political Thermometer high Each day.” Finally, John Brown wrote to William Irvine on August 17, 1789: “The three days last past have been spent in considering the Amendments reported by the Committee as yet we have made very little progress. The Antis viz. Gerry, Tucker &c. appear determined to obstruct & embarrass the Business as much as possible. Is it not surprising that the opposition should come from that quarter?”

The milk-and-water and tub-to-the-whale dismissiveness were uttered by both sides, so too were the threats for a second convention and the call for substituting the amendments emanating from the State Ratifying Conventions, especially the Virginia Ratifying Convention. But in the end, Madison got his way: the First Session was poised to deliver friendly alterations along the lines that he was proposing. In terms of content—other than further fiddling with the religion clauses—the House agreed with the Select Committee Report. But they did drop Madison’s attempt to attach the principles of the Declaration to the Preamble of the Constitution.

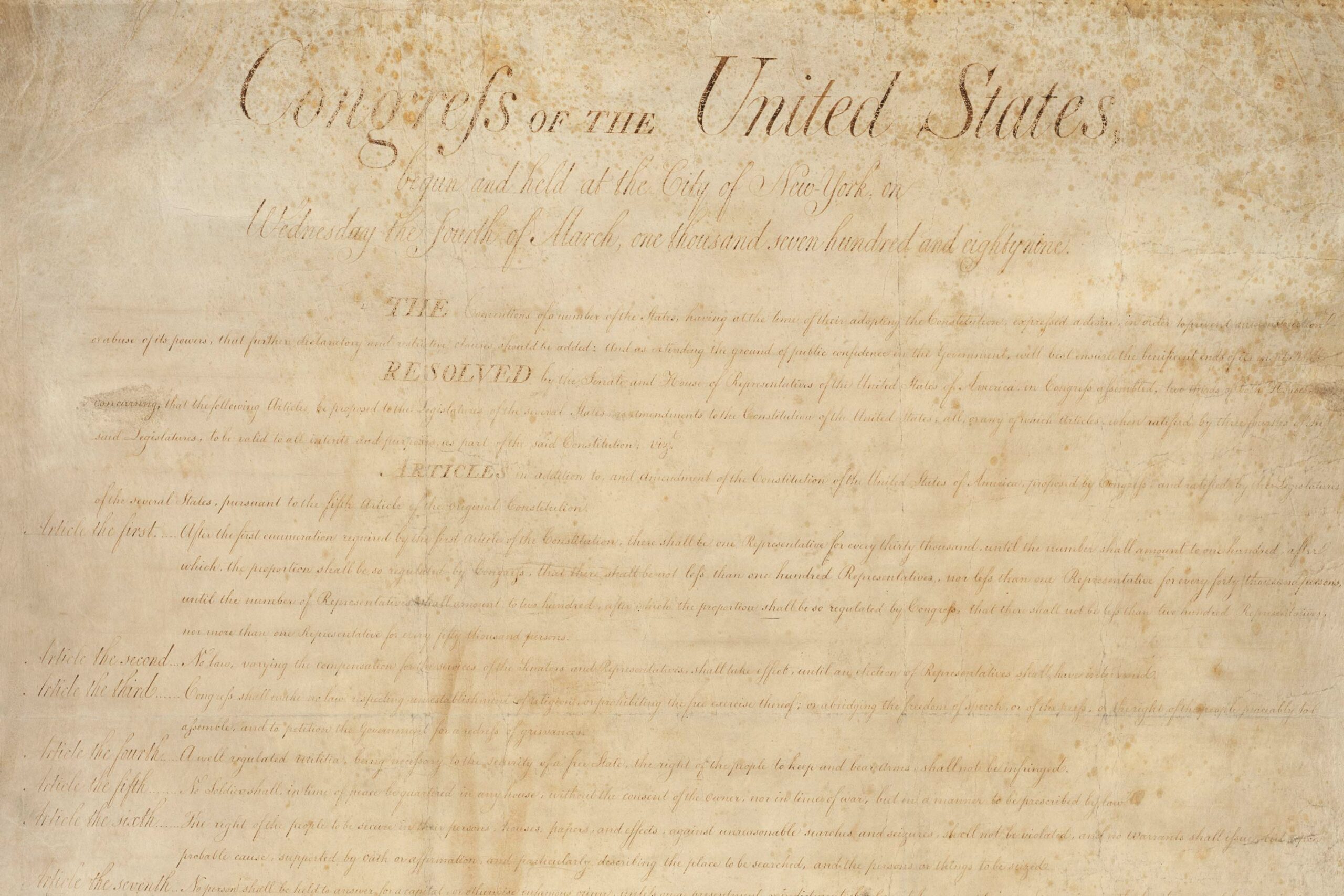

More importantly, Madison’s incorporation method was abandoned in favor of separate Articles of Amendment to be added on to the Constitution. As early as August 4, Roger Sherman expressed his concern about “the form in which they [Bills of Rights] are reported.” Writing to Henry Gibbs, Sherman says: “You have doubtless before this seen the amendments to the Constitution reported by the Committee—they will probably be harmless & Satisfactory to those who are fond of Bills of Rights. I don’t like the form in which they are reported to be incorporated in the Constitution, that Instrument being the Act of the people, ought to be kept entire and amendments made by the Legislatures Should be in addition by way of Supplement.” On August 13, Sherman moved that Madison’s amendment proposals be considered as supplements to the Constitution rather than incorporated within the body of the Constitution. Sherman’s motion was defeated. On August 19, however, Sherman’s motion was revisited and this time it passed. And this changed the whole way we look at the relationship between the original Constitution and the amended Constitution.

Now, thanks to Sherman, Madison’s 39 Proposals were literally pulled out of their Constitutional context of Article, Section, and Clause to become 17 amendments that were to be added on at the end of the original Constitution. For example, the First Amendment dealt with the issue of representation in the House, because popular representation occurred in Article I, Section 2 and Article I comes first in the list of Articles; the Second Amendment covered the pay of representatives; that was in Article I, Section 6 of Madison’s incorporation method because that was next on the list of Madison’s Proposals. The House Third Amendment focused on Article I, Section 9 where we find Madison’s proposed restraints on Congress in the original Constitution. And so on until we have extracted Madison’s 39 Proposals, having eliminated the early ones dealing with the Preamble, and made our way to the end of the Constitution until we arrive at 17 amendments. What was once coherent under Madison because his proposals were intertwined into the clauses of the Constitution are now extracted and bundled as 17 amendments.

Madison’s reaction to the House abandonment of his incorporation form demonstrates once again his notion of principled action. Writing to Alexander White on August 24, Madison lays out his position:

The substance of the report of the Committee of eleven has not been much varied. It became an unavoidable sacrifice to a few who knew their concurrence to be necessary, to the dispatch if not the success of the business, to give up the form by which the amendments when ratified would have fallen into the body of the Constitution, in favor of the project of adding them by way of appendix to it. It is already apparent I think that some ambiguities will be produced by this change, as the question will often arise and sometimes be not easily solved, how far the original text is or is not necessarily superseded, by the supplemental act.

The Bill of Rights tradition that emerged at the state level between 1776 and 1787 was that a bill of rights appeared either 1) as a declaratory preface to the state constitution as a Preamble or mission statement or 2) in the body of the Constitution itself. With the adoption of Sherman’s proposal—the original work of the Framers ought not to be touched—we see for the first time, a bill of rights appearing at the end of a constitution as an amendment. And this is a result of the politics of the Bill of Rights rather than as part of a documentary history based on historical precedent or political philosophy.

August 18 brought relief. Frederick A. Muhlenberg of Pennsylvania wrote to Benjamin Rush on August 18, 1789:

This Day has at length terminated the Subject of Amendments in the Committee of the Whole House, & tomorrow we shall take up the Report & probably agree to the Amendments proposed, & which are nearly the same as the special Committee of eleven had reported them… Mr. Gerry & Mr. Tucker had each of them a long string of Amendments which were not comprised in the Report of the special Committee, & which they stiled Amendments proposed by the several States… Thus far I hope this disagreeable Business is finished, & no other Amendments will I think take place for the present.

Although I am sorry that so much Time has been spent in this Business, and would much rather have had it postponed to the next Session, yet as it now is done I hope it will be satisfactory to our State, and as it takes in the principal Amendments which our Minority had so much at Heart, I hope it may restore Harmony & unanimity amongst our fellow Citizens & perhaps be the Means of producing the much wished for Alterations & Amendments in our State Constitution.

It is a strange yet certain Fact, that those who have heretofore been & still profess to be the greatest Sticklers for Amendments to the Constitution of the U.S. have hitherto thrown every Obstacle they could in their way… It is obvious their Design was to favor their darling Question for calling a (Second) Convention—which however I think is also determined for some Time to come.

The Debates in our House have hitherto gone on with much Candor, firmness and good Humor, but this Day some Gentlemen got into great warmth—more so indeed than ever since our first meeting, so that a frequent call to Order became absolutely necessary—& from this Day forward I expect, especially as we have sat so long and are about to close the session that the Debates will be high. Such I think is the present Temper of the House, that I think the sooner we close the Session the better. I am happy however to find that our Delegation have kept cool and moderate & unanimous.

James Madison confirmed the “exceedingly wearisome” nature of the House debates in a letter to Edmund Randolph dated August 21, 1789:

For a week past the subject of Amendments has exclusively occupied the House of Representatives. Its progress has been exceedingly wearisome not only on account of the diversity of opinions that was to be apprehended, but of the apparent views of some to defeat by delaying a plan short of their wishes, but likely to satisfy a great part of their companions in opposition throughout the Union. It has been absolutely necessary in order to effect any thing to abbreviate debate, and exclude every proposition of a doubtful & unimportant nature. Had it been my wish to have comprehended every amendment recommended by Virginia. I should have acted from prudence the very part to which I have been led by choice. Two or three contentious additions would even now frustrate the whole project.