Dimension IV: The Senate Version

COMMENTARY

The Senate considered the 17 House amendments and compressed them into 12 amendments. Not unexpectedly, there was niggling over the wording of the religion clauses. And not unexpectedly there was concern by the Federalists in the Senate that Madison had created a waste of time. Senator Robert Morris wrote to Richard Peters on August 24:

The Waste of precious time is what has vexed me the most, for as to the Nonsense they call Amendments I never expect that any part of it will go through the various Trials which it must pass before it can become a part of the Constitution.… I am however strengthened in pronouncing this Sentence, by the opinions of our Friends Clymer & Fitzsimmons who said Yesterday that the business of Amendments was now done with in their House & advised that the Senate should adopt the whole of them by the Lump as containing neither good or Harm being perfectly innocent. I expect they will lie on our Table for some time, but I may be mistaken having had but little conversation with any of the Senators on this Subject.

The Senate showed their crankiness right from the start. The Diary of William Maclay on August 25, 1789 records the following: “The Amendments …were treated contemptuously by Z {Izard}, Langdon and Mr. Morris. Z moved they should be postponed to next Session. Langdon seconded & Mr. Morris got up and spoke angrily but not well. They however lost their Motion and Monday was assigned for the taking them up.” Richard Henry Lee in a letter to Charles Lee dated August 28, 1789 noted his concern with Federalist politics of postponement:

The enclosed paper will show you the amendments passed the House of Representatives to the Constitution. They are short of some essentials, as Election interference & Standing Army &c. I was surprised to find in the Senate that it was proposed we should postpone the consideration of Amendments until Experience had shown the necessity of any—as if experience was more necessary to prove the propriety of those great principles of Civil liberty which the wisdom of Ages has found to be necessary barriers against the encroachments of power in the hands of frail Men!

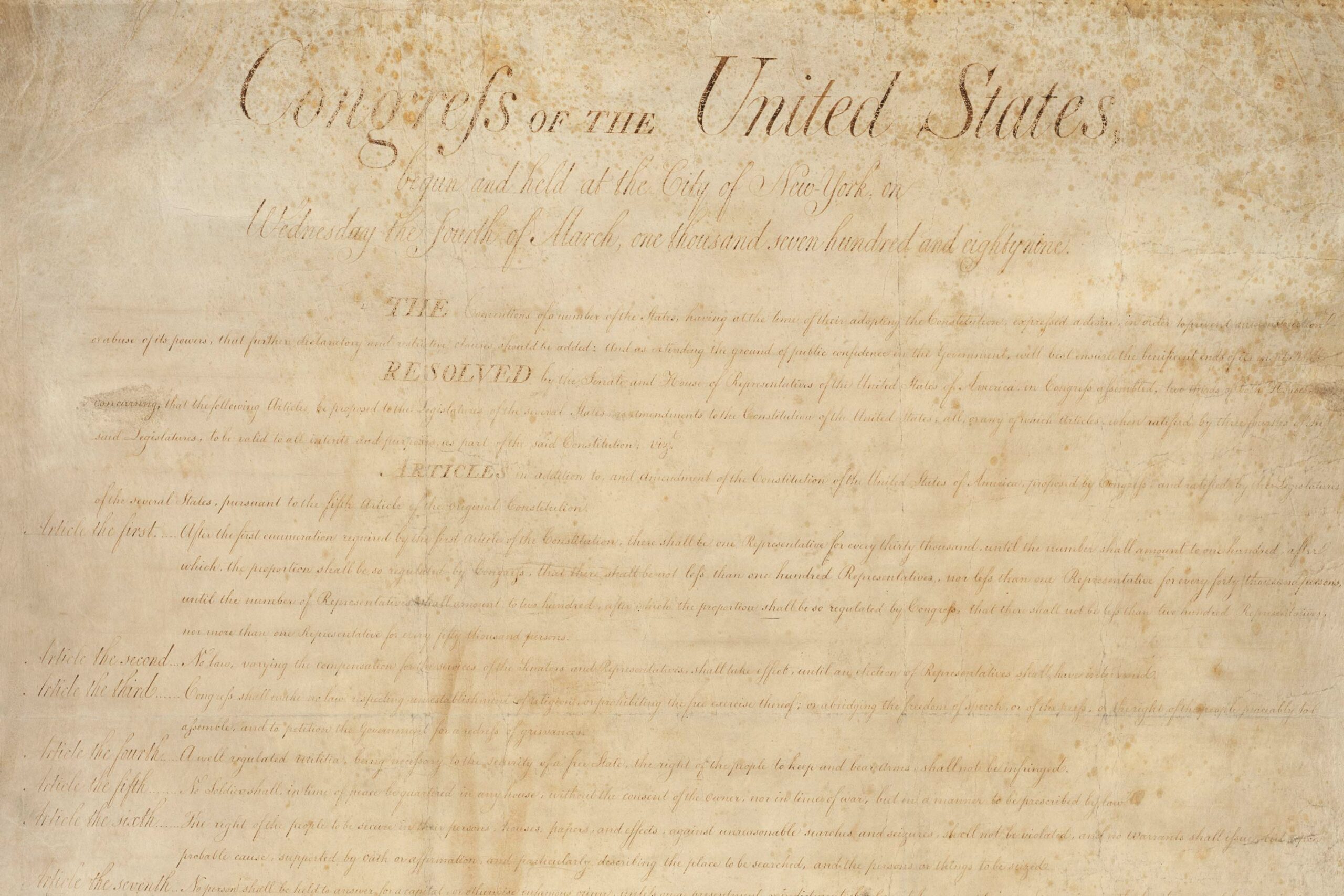

Among the most important Senate alterations to the House amendments was the deletion of what Madison considered to be the cornerstone of his 39 Proposals. Three of them took Jefferson up on his observation that every government should have a bill of rights. In the context of their exchange, Jefferson probably meant that the people expected a Bill of Rights to limit the reach of the federal government, but Madison took him literally to include the state governments as well. Thus he included the three essential restraints on all governments as additions to Article I, Section 10 of the original Constitution. These three limitations on behalf of conscience, press, and juries survived the Sherman reordering project and appeared as House Amendment XIV! It should not be surprising that the Senate—the branch designed to represent the States—should remove these three limitations on the States. What is surprising is that it is from the Senate that we get “or to the people” added to the delegation-of-powers clause in Senate Amendment XII!

Roger Sherman expressed his approval of the Senate actions to Samuel Huntington September 17, 1789: “Your Excellency has doubtless seen the amendments proposed to be made to the Constitution as passed by the House of Representatives, enclosed is a copy of them as amended by the Senate, wherein they are considerably abridged & I think altered for the better.” Sherman does not elaborate on what alterations the Senate did for the better. But given that he was a partly national-partly federal delegate at the Philadelphia Convention, one can surmise that he approved of the omission of the religion, press, and jury restraints on the States in House Amendment XIV. What is clear is that Sherman is going to support the Senate Version when he is selected by the House to the Conference Committee.

Benjamin Goodhue, however, expressed his disappointment with the Senate Version to Samuel Phillips in a letter dated September 13, 1789: “The Amendments have come from the Senate with amendments, such as striking out the word vicinage as applied to Jurors, and have struck out the limitation of sums for an appeal to the federal Court &c. Those two have been the darling objects with the Virginians who have been the great movers in amendments, and I am suspicious, it may mar the whole business, at least so far as to refer it to the next session.”

James Madison also wrote of his disapproval of the Senate Version to Edmund Pendleton on September 14, 1789:

The Senate have sent back the plan of amendments with some alterations which strike in my opinion at the most salutary articles. In many of the States juries, even in criminal cases, are taken from the State at large; in others from districts of considerable extent—in very few from the County alone. Hence a dislike to the restraint with respect to vicinage, which has produced a negative on that clause. A fear of inconvenience from a constitutional bar to appeals below a certain value, and a confidence that such a limitation is not necessary, have had the same effect on another article. Several others have had a similar fate. The difficulty of uniting the minds of men accustomed to think and act differently can only be conceived by those who have witnessed it.