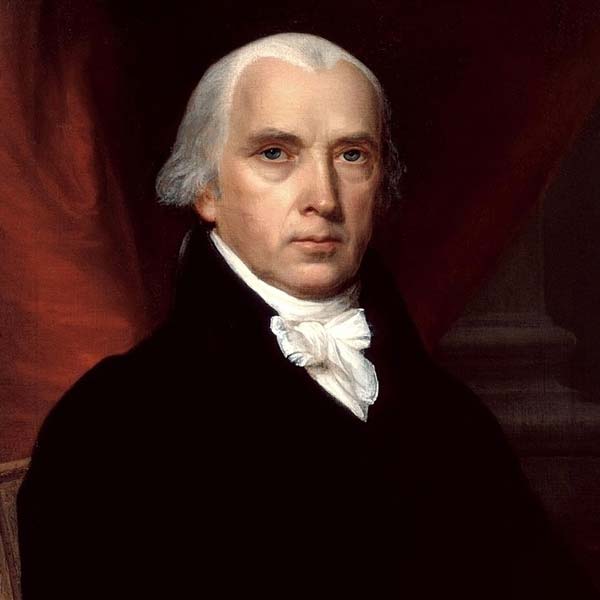

Letter to James Madison about Improving the Constitution

July 31, 1788

Introduction

James Madison wrote to Thomas Jefferson in Paris, where Jefferson was serving as Ambassador, that the U.S. Constitution had been ratified, thus avoiding the danger of a second convention, as well as the adoption of unfriendly amendments as a condition for ratification. Madison was relieved and optimistic. In this response, Jefferson reminded Madison that there was still much work to be done: the Constitution is a “good canvas” that needs to be retouched with a bill of rights. Madison had heard this argument before, but in 1787–1788 he was focused on creating the Constitution, and then seeing it adopted. With the adoption of the Constitution, Madison was finally willing to entertain the idea of adopting a bill of rights. But this adoption, he would argue, must not undermine the Constitution. There was no going back to the Articles of Confederation in the move forward to incorporate a bill of rights. Jefferson, less worried by the dangers of constitutional revision, would soon experience the tumult of the French Revolution.

Source: To James Madison from Thomas Jefferson, 31 July 1788 (Founders Online). For ease of reading, we have added paragraph divisions.

https://goo.gl/m1Jz4E

. . . I sincerely rejoice at the acceptance of our new Constitution by nine states. It is a good canvas, on which some strokes only want retouching. What these are, I think are sufficiently manifested by the general voice from north to south, which calls for a bill of rights. It seems pretty generally understood, that this should go to juries, habeas corpus, standing armies, printing, religion and monopolies. I conceive there may be difficulty in finding general modifications of these, suited to the habits of all the states.

But if such cannot be found, then it is better to establish trials by jury, the right of habeas corpus, freedom of the press and freedom of religion, in all cases, and to abolish standing armies in time of peace, and monopolies in all cases, than not to do it in any. The few cases wherein these things may do evil, cannot be weighed against the multitude wherein the want of them will do evil. In disputes between a foreigner and a native, a trial by jury may be improper. But if this exception cannot be agreed to, the remedy will be to model the jury by giving the mediatas linguae,[1] in civil as well as criminal cases. Why suspend the habeas corpus in insurrections and rebellions? The parties who may be arrested, may be charged instantly with a well-defined crime. Of course, the judge will remand them. If the public safety requires that the government should have a man imprisoned on less probable testimony in those than in other emergencies, let him be taken and tried, retaken and retried, while the necessity continues, only giving him redress against the government, for damages. . . .

A declaration, that the federal government will never restrain the presses from printing any thing they please, will not take away the liability of the printers for false facts printed. The declaration that religious faith shall be unpunished, does not give impunity to criminal acts dictated by religious error. The saying there shall be no monopolies, lessens the incitements to ingenuity, which is spurred on by the hope of a monopoly for a limited time, as of 14 years; but the benefit even of limited monopolies is too doubtful to be opposed to that of their general suppression. If no check can be found to keep the number of standing troops within safe bounds, while they are tolerated as far as necessary, abandon them altogether, discipline well the militia, and guard the magazines with them. More than magazine guards will be useless, if few, and dangerous, if many. No European nation can ever send against us such a regular army as we need fear, and it is hard if our militia are not equal to those of Canada or Florida. My idea, then, is that though proper exceptions to these general rules are desirable and probably practicable, yet if the exceptions cannot be agreed on, the establishment of the rules, in all cases, will do ill in very few. I hope, therefore, a bill of rights will be formed to guard the people against the federal government, as they are already guarded against their state governments, in most instances.

The abandoning the principle of necessary rotation in the Senate has, I see, been disapproved by many; in the case of the President, by none. I readily therefore suppose my opinion is wrong, when opposed by the majority as in the former instance, and the totality as in the latter. In this however I should have done it with more complete satisfaction, had we all judged from the same position. . . .

- Medietas linguae, a Latin expression meaning “half tongue,” indicates that in the criminal trial of a foreigner or alien, a jury has been composed one half of natives and one half of foreigners.