Origins of the Bill of Rights Series: The State and Continental Roots of the Bill of Rights

Introduction

The main features of the Bill of Rights were already embedded in the State Constitutions; in other words there was an American tradition of rights rather than simply a concoction by Madison to appease some disgruntled Antifederalists. And it is also a bit too dramatic to say if it weren’t for the Antifederalists there would be no Bill of Rights.

But what this table does not do give us is the full expression of rights contained in the State Constitutions. If we were to engage in this exercise, we would also see that “Madison’s 39 steps” are actually closer to the full list of rights in the state constitutions than even the Bill of Rights itself. The final Bill of Rights is actually an abbreviated version of what might have been. In particular, the first four on Madison’s list that reiterate the principles of the Declaration of Independence can be found in the State Declarations and Constitutions.

Three rights are unanimously represented in all the State Constitutions, Madison’s list and the Bill of Rights: rights of conscience/free exercise of religion; local impartial jury; and common law and jury trial. There are, perhaps, three surprises by the less than full representation; no establishment of religion/no favored sect; freedom of speech; and no double jeopardy. We must turn our attention to the State Ratifying Conventions and the First Congress for illumination on these three as well as the move in language from conscience to free exercise.

| Content of Bill of Rights | Virginia | New Jersey | Pennsylvania | Delaware | Maryland | North Carolina | Georgia | New York | North Carolina | Massachusetts | New Hampshire | Declaration and Resolves of First Continental Congress, 1774 | Declaration of Independence, 1776 | Articles of Confederation, 1777 | Northwest Ordinance, 1787 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Established Religion/Favored Sect | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||

| Rights of Conscience/Free Exercise | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Freedom of Speech | X | X | |||||||||||||

| Freedom of Press | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Freedom of Assembly | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| Freedom to Petition | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Keep and Bear Arms/Militia | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Quartering of Troops | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| Double Jeopardy | X | ||||||||||||||

| Self Incrimination | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Due Process of Law | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Takings/Just Compensation | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||

| No Excessive Bail and Fines | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| No Cruel and/or Unusual Punishments | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| No Unreasonable Searches/Seizures | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Speedy/Public Trial in Criminal Cases | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| Nature of Accusation | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Confrontation of Witnesses | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Compulsory Witness | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| Assistance of Counsel | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Rights Retained by the People | |||||||||||||||

| $ Limitation on Appeals | |||||||||||||||

| Common Law and Jury Trial | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| (Local) Impartial Jury for All Crimes | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Grand Jury for Loss of Life or Limb | X | ||||||||||||||

| Reservation of Nondelegated Powers | X | X | |||||||||||||

| Totals | 17 | 6 | 20 | 19 | 17 | 17 | 7 | 8 | 6 | 20 | 20 | 5 | 2 | 5 | 8 |

Commentary

On May 15, 1776, the Second Continental Congress issued a “Resolve” to the thirteen colonial assemblies: “adopt such a government as shall, in the opinion of the representatives of the people, best conduce to the happiness and safety of their constituents in particular, and America in general.” Between 1776 and 1780, elected representatives met in deliberative bodies as founders and chose republican governments. Connecticut and Rhode Island retained their colonial charters, but the other eleven reaffirmed the American covenanting tradition and created governments dedicated to securing rights. What transpired was the most extensive documentation of the rights of the people the world had ever witnessed.

We have reproduced three State Constitutions: Virginia, the first to be written and adopted one week prior to the Declaration of Independence; New Jersey, adopted on July 2, 1776, and the first to exclude a prefatory bill of rights; and Pennsylvania, the third constitution adopted and considered the most radical. Together, they capture the diversity and uniformity of the revolutionary conversation over bicameralism, separation of powers, length of service, and how rights were to be secured by a republican frame of government. They express the American covenanting tradition reinforced by the enlightenment doctrine of natural rights that it is the right of the people to choose their form of government. These constitutions are practical expressions of the ideal that government ought to be founded on deliberation and consent rather than accident and force.

Seven states attached a prefatory declaration of rights to the frame of government: Virginia (June 1776), Delaware (September 1776), Pennsylvania (September 1776), Maryland (November 1776), North Carolina (December 1776), Massachusetts (March 1780), and New Hampshire (June 1784). These declarations were, in effect, a preamble stating the purposes for which the people have chosen the particular form of government. There is a remarkable uniformity among the seven states with regard to the kinds of civil and criminal rights that were to be secured. The Virginia, Delaware, Pennsylvania, and Massachusetts Declarations capture both the similarity, and the subtle differences, given to “the free exercise of religion,” “the establishment of religion,” the freedom of press, the right to petition, the right to bear arms, the quartering of troops, the protection from unreasonable searches and seizures, the centrality of trial by jury, the right to confrontation of witnesses and the right to counsel, the importance of “due process of law,” and the protection against excessive fines and cruel and unusual punishment.

Four of the states decided not to “prefix” a bill of rights to their newly founded republican constitutions: New Jersey (July 1776), Georgia (February 1777), New York (April 1777), and South Carolina (March 1778). Nevertheless, each had prefaces confirming the authority of the covenanting tradition and also, most importantly, incorporated individual protections into the body of their constitutions.

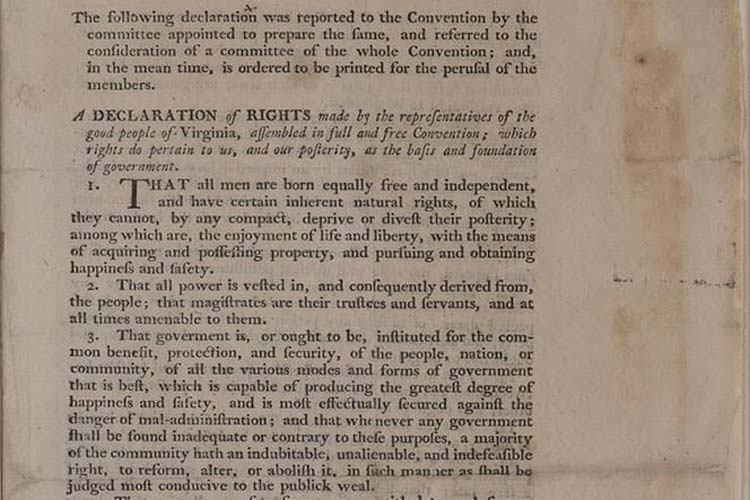

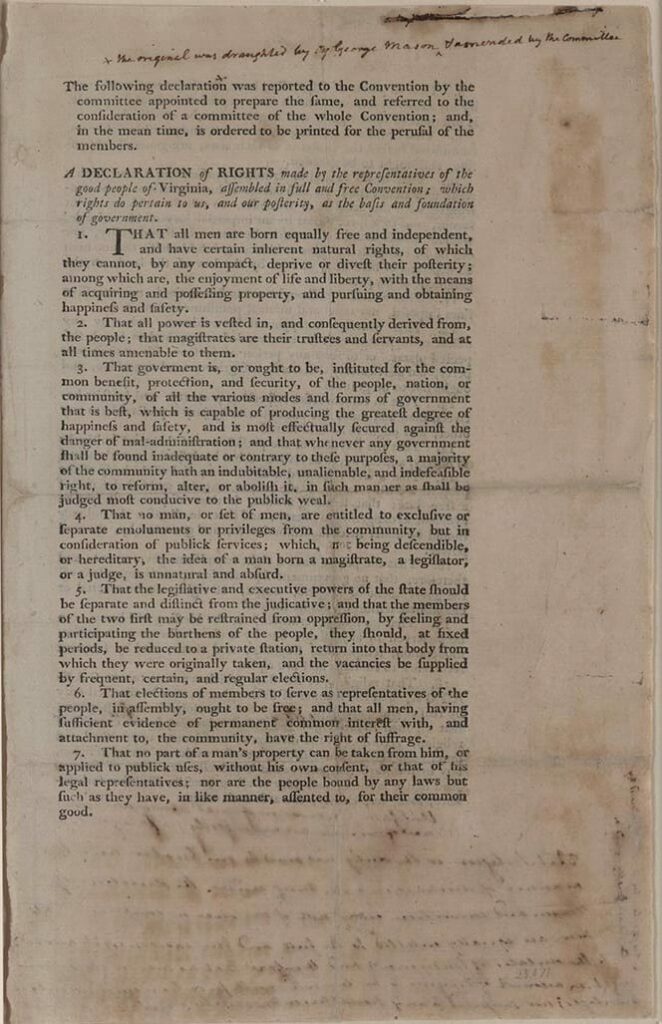

Virginia

The Virginia Declaration of Rights was adopted by the House of Burgesses in June 1776. Among the delegates were George Mason, the most important contributor, and twenty-five-year-old James Madison who drafted the section on the “free exercise of religion.” The “rights” listed in the first five sections might strike the contemporary reader as odd; it is important to remember, however, that among the most fundamental rights articulated by the revolutionary generation was the right of the people to choose their form of government. Sections six through fourteen cover familiar ground. Most of the civil rights and criminal procedures listed were part of the Americanized version of the “rights of Englishmen” tradition. Section fifteen reflects the traditional republican argument that free government could survive only if the people were virtuous. Because colonial America turned to religion to perform this important political function, there was a presumption that religion had an “established” status. In 1776, the Anglican church was the established church of Virginia, and there is nothing in the Virginia Bill of Rights that challenges this establishment. On the other hand, Madison’s natural right argument, incorporated in section sixteen, challenged the public dimension of religion on the ground that the exercise of religion should be “free” of “force or violence.”

The same Convention also framed and adopted the Virginia Constitution. The first, and longest, section anticipates the Declaration of Independence: Twenty-one separate indictments are listed against King George. Section two provides the authorization for establishing a new foundation. Sections three through thirteen pertain to the bicameral legislature; and the remainder focus on the election of executive officers. Section twenty-one lays the foundation for the Northwest and Southwest Territories.

New Jersey

The 1776 New Jersey Constitution, framed by a convention that met from May 26 through July 3, was the second to be adopted and the first to omit a prefatory Bill of Rights. Nevertheless, the constitution appeals to “the nature of things” and the American covenanting tradition. Moreover, civil rights and criminal procedures are addressed in four of the thirty-nine articles. Article XVI provides that “all criminals shall be admitted to the same privileges of witness and counsel, as their prosecutors doe or shall be entitled to,” and Article XXII confirms the common law tradition with the trial by jury being given permanent protection. Two articles address the issue of religious rights. Article XVIII guarantees to all “the inestimable privilege of worshipping Almighty God in a manner agreeable to the dictates of his own conscience,” and proclaims that no one shall ever be obliged to support financially any ministry “contrary to what he believes to be right, or has deliberately or voluntarily engaged himself to perform.” Article XVIX states that there “shall be no establishment of any one religious sect in this Province, in preference to another,” and that all persons of “any Protestant sect shall fully and freely enjoy every privilege and immunity, enjoyed by others their fellow subjects.” New Jersey was the first state to prohibit the establishment of a specific sect as the official religion.

Pennsylvania

The Pennsylvania Constitution, prefaced by a Preamble and Declaration of Rights, was framed by a specially-elected convention that met from mid-July to the end of September 1776. Although the document was not submitted to the people for ratification, it expresses the radical dimension of the conversation over what frame of government would best secure the rights of the people: Pennsylvania was the only state to choose a unicameral rather than a bicameral legislature. Although the legislature was very powerful, the constitution calls for an “open” assembly with policy making taking place under the full scrutiny of an informed electorate. In section forty-seven, the framers created an elected Council of Censors to provide periodic review of the operation of the laws and institutions “in order that the freedom of the commonwealth may be preserved inviolate for ever.” This model was subsequently praised by Jefferson in his Notes on Virginia and criticized by Madison in Federalist 47-51.

John Adams’s 1779 judgment that the Pennsylvania Bill of Rights “is taken almost vebatim from that of Virginia” is correct as far as it concerns the common law tradition. Nevertheless, all sixteen deserve to be reproduced in their entirety in order to appreciate the remarkable uniformity and subtle differences among the states. It is particularly important to note that Pennsylvania repeats the claim that “a firm adherence to justice, moderation, temperance, industry, and frugality are absolutely necessary to preserve the blessings of liberty,” and that only Christians are eligible to hold office. Also noteworthy are the sections dealing with searches and seizures, freedom of speech, the right to bear arms, “the natural inherent right to emigrate,” and the right to assemble.

Delaware

The Delaware Declaration of Rights followed Pennsylvania and appealed to natural rights and the common law tradition. Of particular interest is the concern for the political rights of the people: the right to hold officials accountable, the right to participate in government and to petition for redress of grievances, and the right to no ex post facto laws.

Massachusetts

The Massachusetts Declaration of Rights and Constitution, drafted over a six-month period, was adopted in Spring 1780. It was the first to be ratified by the people rather than by the people’s representatives. Actually, the 1780 Constitution was a revised version of the 1778 Constitution rejected in large part because of the absence of a Bill of Rights. The town of Boston declared “that all Forms of Government should be prefaced by a Bill of Rights; in this we find no Mention of any.” Eleven towns also objected to the denial of the right of suffrage to free “negroes, Indians, and mulattoes” in Article V. The Essex Resultthe combined judgment of the twelve towns of Essex County reached at a county conventionalso expressed concern that the foundation was illegitimate because the people were excluded from the adoption process.

The Massachusetts Preamble confirmed the “right of the people to set up what government they believe will secure their safety, prosperity, and happiness.” The provisions in “Part the First” dealing with search and seizure, self-incrimination, confrontation of witnesses, self-incrimination, cruel and unusual punishments, freedom of press, the right to petition, and that no one shall be deprived of “life, liberty, or estate, but by the judgment of his peers, or the law of the land,” were common among all the states that adopted a Bill of Rights. Massachusetts, also included specific political rights of the people: the right to no ex post facto laws, frequent elections, an independent judiciary, and the right to a strict separation of governmental powers “to the end that it may be a government of laws and not of men.” As was the case in Virginia and Pennsylvania, the need for “piety, justice, moderation, temperance, industry, and frugality” was listed in the Bill of Rights. What is distinctive about Massachusetts is that the virtue of the people was to be secured by established religion. The third “right” was that of the citizens to support, financially, the establishment of Protestantism as the public religion. To be sure, no one particular sect would be given preference over another; all were “equally under the protection of the law” and the “free exercise” of religion was protected.

Madison and Jefferson. Virginia entered unfamiliar territory with the disestablishment of the Anglican church in 1779. Nevertheless, there were two competing models to which legislators could turn. The Massachusetts model endorsed the establishment of the Christian Protestant religion and, to that end, the legislature was constitutionally mandated to tax inhabitants for the support of public religious instruction. The taxpayer, nevertheless, was free to name the specific religion that was to receive the assessment. On the other hand, the Pennsylvania model warned that such taxation threatened the right of an individual to the free exercise of religion. In December 1784, the Virginia Assembly considered an Assessment Bill, consistent with the Massachusetts model, that would financially support the propagation of Christianity as the state religion. James Madison, the principle author of this protest addressed to the Virginia Assembly, urged the legislators to reject the proposed legislation. In the process, Madison pushed the national conversation even further in the direction of individual free exercise of religion and away from community endorsed religion. The practical manifestation of Madison’s efforts was the Assembly adoption in 1785 of Jefferson’s Statute of Religious Liberty introduced in 1779. The Virginia Senate passed the statute in January 1786.