Prologue: The Making of the American Mind

How did the American mind change between 1760 and 1776, and why did it change? Or perhaps the question is, what led to the creation of the “American Mind” as described by Thomas Jefferson in his letter to Henry Lee of 1825? Why move from petition to independence? What was in the air in that critical period? As John Adams wrote in his letter to Hezekiah Niles in 1818, “The Revolution was in the minds and hearts of the people, a change in their religious sentiments of their duties and obligations”—and at a certain point they ceased “to pray for the king and queen and all the royal family” and began instead “to pray for the Continental Congress and all the thirteen state congresses.” Adams then described several “characters the most conspicuous, the most ardent and influential” who affected this shift in public thought through their writings, speeches, and sermons. We refer to these influential arguments as “out-of-doors” because they take place in the public realm, though many would eventually influence the debates in Congress.

What stirred the “American mind” to transition from allegiance to the King and Parliament in 1760 to first resisting and petitioning for redress of grievances and ultimately to move to independence? To be sure, Americans were influenced by the ideas of Algernon Sidney, John Locke, and The Spectator essays, with their emphasis on natural liberty, the need for consent in government, and the limited purposes of just government. But the minds of Americans were also moved over time by the acts of Parliament and the King between 1763 and 1776. With each attempt by Great Britain to coerce the colonies, writers and preachers, in their pamphlets and sermons, opened the American mind to see that their rights were being violated. At the same time, they raised even larger questions, such as, what are the legitimate ends and powers of government, and what distinguishes good from unjust government? As American colonists considered these questions, they moved—gradually but steadily—toward considering independence. We include five examples of the most influential sermons and pamphlets below.

JAMES OTIS, THE RIGHTS OF THE BRITISH COLONIES ASSERTED AND PROVED, 1764

James Otis (1725-1783) was born into a family that had emigrated from England to Massachusetts in the early part of the 1600s. He was drawn into the great taxation debates following the Stamp Act of 1764, as were many other prominent professionals in the colonies. He graduated with a degree in law from Harvard. Otis acquired a reputation for being a zealous and successful defender of individual rights. He, as well as many others, had the ability to locate the immediate struggle over taxation within a larger theoretical context. Most importantly, Otis—following Locke and Sidney—argues that government ought not to be based on blind necessity or force. Rather, the people have the ability and, more importantly, the right to choose the form of government under which they shall live.

RICHARD BLAND, AN INQUIRY INTO THE RIGHTS OF THE BRITISH COLONIES, 1766

Richard Bland (1710-1776) was a member of the colonial Virginia House of Burgesses from 1742 until 1775. He was also elected to the first Continental Congress and to the first House of Delegates under Virginia’s new state constitution. Thomas Jefferson considered Bland to be “one of the oldest, ablest and most respected” of the many politicians to address the crisis with Britain between 1763 and 1776. His 1766 pamphlet, An Inquiry into the Rights of the British Colonies, was one of the first defenses of the colonial position on taxation. The pamphlet is important because of Bland’s critical analysis of virtual representation. He set the tone for what became central to the American concept of political rights during the next decade: there should be no taxation without actual representation. Bland appeals to “the fundamental Principles of the English Constitution,” the Saxon tradition, the “Principle of the Law of Nature,” and the separate colonial charters, as authoritative sources.

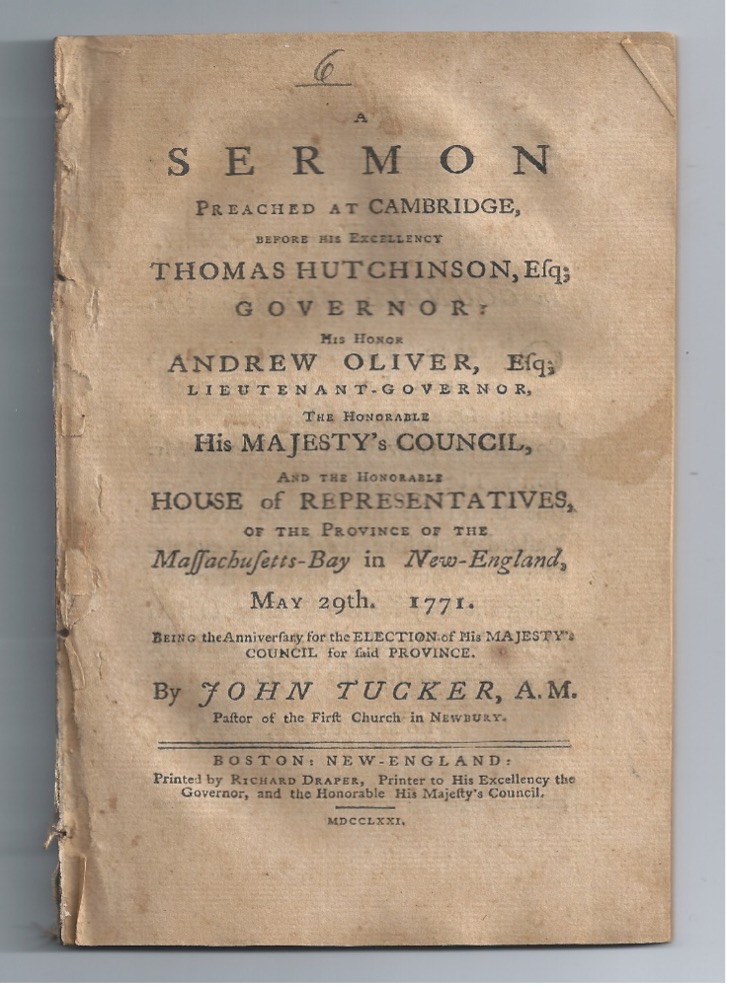

JOHN TUCKER, AN ELECTION SERMON, 1771

John Tucker (1719-1792) studied theology at Harvard and graduated in 1741. Pastor Tucker’s sermon, delivered in May 1771 before numerous political figures, is an example of how the revolutionary-era participants placed the particular dispute over taxation policies within a more general theoretical, even, especially in Tucker’s case, divine, framework. It is important to note Tucker’s argument that the enlightenment principles of Locke and the Protestant Christian religion endorse the right to resist the agents of corruption and slavery: “the voice of reason…may be said to be the voice of God.” He also demonstrates how the American position is consistent with the constitutional heritage bequeathed by the Magna Carta.

SAMUEL ADAMS, BOSTON GAZETTE, UNTITLED, 27 FEBRUARY 1769 AND RIGHTS OF THE COLONISTS, 20 NOVEMBER 1772

Samuel Adams’ writing on behalf of the rights of the colonists during the critical period between 1764 and 1774 was extensive. His writing joined together the separate Lockean natural right doctrine, the rights of Englishmen incorporated in the 1689 Bill of Rights, Blackstone’s reliance on courts of law, and the American covenanting tradition to support the right of Bostonians to resist the importation of British law. In his final analysis, however, Adams realized that the strongest case for the colonial position was the “natural rights of the colonists as men.”

THOMAS PAINE, COMMON SENSE, 14 FEBRUARY 1776

Of these “out-of-doors” writers, none had a more direct influence on Congress’ deliberations on independence than Thomas Paine. His pamphlet “Common Sense,” published in January of 1776, was widely read and praised for the strength of its arguments by many delegates in the Second Continental Congress. In fact, we find in several letters mention of delegates sending copies to other delegates or influential political persons in their home state. Paine’s pamphlet was also widely read aloud in the streets of American cities, further growing public support for independence and bolstering enlistments in the state militias and recruiting for the Continental Army. Common Sense builds on some of the ideas of right and rights in the previous pamphlets and sermons cited above, but presents readers with a thoroughly practical or pragmatic case for American independence, as the title suggests.

Commentary by Christopher Burkett with documentary support by Gordon Lloyd and Josh Distel.