Second Continental Congress: December 6, 1775

December 6, 1775

Congress agrees with the response of The Committee on Proclamation to the King’s Proclamation of August 23rd: “the right to resist” is part of the British legal tradition and the colonies are not in rebellion. We are engaged in an unnatural civil war. The Secret Committee signs a contract for gunpowder and Robert J. Livingston is proud of victory in Canada but ashamed of the behavior of the troops.

Link to date-related documents

Journals of the Continental Congress [Edited]

The Committee of Claims reported that a reimbursement is due to Robert Erwin.

Ordered, That the account be paid.

Resolved, That the three prisoners taken by Captain Abraham Whipple be delivered to the committee of safety of the Colony of Pennsylvania, who are directed to secure them in safe custody.

Resolved, That the committee of inspection of this city and liberties of Philadelphia purchase flints for the use of the Continent, and that in making the purchase, attention be paid to the resolution of Congress against raising the price of goods.

The Congress resumed the consideration of the instructions to be given to the Committee of Claims.

Resolved, That the charge for bounty in the account exhibited by Rhode Island against the Continent be not allowed.

The Committee, to whom the petition of Captain Dougal McGregor was referred, delivered a report that was read and agreed to.

Resolved, That it is the opinion of the Committee that the circumstances stated in the petition will not justify a license to export the said lumber and naval stores, contrary to the rules of American Association. But the Committee is willing to consider a revised petition.

Congress resumed consideration of the report of the committee on proclamations on the King’s Proclamation of August 23 which was debated by paragraphs and agreed to.

The Report of the Committee on Proclamations

We, the Delegates of the thirteen United Colonies in North America, have taken into our most serious consideration, a Proclamation issued from the Court of St. James’s on the Twenty-Third day of August last. The name of Majesty is used to give it a sanction and influence; and, on that account, it becomes a matter of importance to wipe off, in the name of the people of these United Colonies, the aspersions which it is calculated to throw upon our cause; and to prevent, as far as possible, the undeserved punishments, which it is designed to prepare, for our friends.

We are accused of “forgetting the allegiance which we owe to the power that has protected and sustained us.” Why all this ambiguity and obscurity in what ought to be so plain and obvious, as that he who runs may read it? What allegiance is it that we forget? Allegiance to Parliament? We never owed–we never owned it. Allegiance to our King? Our words have ever avowed it,–our conduct has ever been consistent with it. We condemn, and with arms in our hands,–a resource which Freemen will never part with,–we oppose the claim and exercise of unconstitutional powers, to which neither the Crown nor Parliament were ever entitled. By the British Constitution, our best inheritance, rights, as well as duties, descend upon us: We cannot violate the latter by defending the former: We should act in diametrical opposition to both, if we permitted the claims of the British Parliament to be established, and the measures pursued in consequence of those claims to be carried into execution among us. Our sagacious ancestors provided mounds against the inundation of tyranny and lawless power on one side, as well as against that of faction and licentiousness on the other. On which side has the breach been made? Is it objected against us by the most inveterate and the most uncandid of our enemies, that we have opposed any of the just prerogatives of the Crown, or any legal exertion of those prerogatives? Why then are we accused of forgetting our allegiance? We have performed our duty: We have resisted in those cases, in which the right to resist is stipulated as expressly on our part, as the right to govern is, in other cases, stipulated on the part of the Crown. The breach of allegiance is removed from our resistance as far as tyranny is removed from legal government. It is alleged, that “we have proceeded to an open and avowed rebellion.” In what does this rebellion consist. It is thus described—“Arraying ourselves in hostile manner, to withstand the execution of the law, and traitorously preparing, ordering, and levying war against the King.” We know of no laws binding upon us, but such as have been transmitted to us by our ancestors, and such as have been consented to by ourselves, or our representatives elected for that purpose. What laws, stamped with these characters, have we withstood? We have indeed defended them; and we will risk everything, do everything, and suffer everything in their defense. To support our laws, and our liberties established by our laws, we have prepared, ordered, and levied war: But is this traitorously, or against the King? We view him as the Constitution represents him. That tells us he can do no wrong. The cruel and illegal attacks, which we oppose, have no foundation in the royal authority. We will not, on our part, lose the distinction between the King and his Ministers: happy would it have been for some former Princes former Princes, had it been always preserved on that part of the Crown.

Besides all this, we observe, on this part of the proclamation, that “rebellion” is a term undefined and unknown in the law; it might have been expected that a proclamation, which by the British constitution has no other operation than merely that of enforcing what is already law, would have had a known legal basis to have rested upon. A correspondence between the inhabitants of Great Britain and their brethren in America, produced, in better times, much satisfaction to individuals, and much advantage to the public. By what criterion shall one, who is unwilling to break off this correspondence, and is, at the same time, anxious not to expose himself to the dreadful consequences threatened in this proclamation–by what criterion shall he regulate his conduct? He is admonished not to carry on correspondence with the persons now in rebellion in the colonies. How shall he ascertain who are in rebellion, and who are not? He consults the law to learn the nature of the supposed crime: the law is silent upon the subject. This, in a country where it has been often said, and formerly with justice, that the government is by law, and not by men, might render him perfectly easy. But proclamations have been sometimes dangerous engines in the hands of those in power; Information is commanded to be given to one of the Secretaries of states, of all persons “who shall be found carrying on correspondence with the persons in rebellion, in order to bring to condign punishment the authors, perpetrators, or abettors, of such dangerous designs.” Let us suppose, for a moment, that some persons in the colonies are in rebellion, and that those who carry on correspondence with them, might learn by some rule, which Britons are bound to know, how to discriminate them; Does it follow that all correspondence with them deserves to be punished? It might have been intended to apprize them of their danger, and to reclaim them from their crimes. By what law does a correspondence with a criminal transfer or communicate his guilt? We know that those who aid and adhere to the King’s enemies, and those who correspond with them in order to enable them to carry their designs into effect, are criminal in the eye of the law. But the law goes no farther. Can proclamations, according to the principles of reason and justice, and the constitution, go farther than the law?

But, perhaps the principles of reason and justice, and the constitution will not prevail: Experience suggests to us the doubt: If they should not, we must resort to arguments drawn from very different source. We, therefore, in the name of the people of these United Colonies, and by authority, according to the purest maxims of representation, derived from them, declare, that whatever punishment shall be inflicted upon any persons in the power of our enemies for favoring, aiding, or abetting the cause of American liberty, shall be retaliated in the same kind, and the same degree upon those in our power, who have favored, aided, or abetted, or shall favor, aid, or abet the system of ministerial oppression. The essential difference between our cause, and that of our enemies, might justify a severer punishment: The law of retaliation will unquestionably warrant one equally severe.

We mean not, however, by this declaration, to occasion or to multiply punishments; Our sole view is to prevent them. In this unhappy and unnatural controversy, in which Britons fight against Britons, and the descendants of Britons, let the calamities immediately incident to a civil war suffice. We hope additions will not from wantonness be made to them on one side: We shall regret the necessity, if laid under the necessity, of making them on the other.

A petition and memorial from Colonel J. Bull, was presented to Congress and read.

Resolved, That they be considered next Friday.

That the president inform Major Preston of the foregoing resolution.

A letter from General Washington, dated 28th November, being received, was read.

Resolved, That the same be taken into consideration tomorrow morning.

Adjourned to 9 o’Clock tomorrow.

Secret Committee Minutes of Proceedings

At a meeting of the Committee of Secrecy, present Samuel Ward, Benjamin Franklin, Silas Deane, Philip Livingston, Josiah Bartlett, Francis Lewis. A Contract was entered into between J. Chevalier & Peter Chevalier of the City of Philadelphia Merchants of the one part & the said Committee on the other part.

That a voyage be immediately undertaken, to some proper port or ports in Europe for the speedy procuring of twenty tons of good gunpowder or if the Gunpowder cannot be had, as much salt petre with a proportion of 15 lb of Sulphur to every hundred weight of salt petre as will be sufficient to make that quantity of Gun Powder, one thousand stand of good Arms, three thousand good plain double bridled gunlocks & twenty tons of Lead.

Robert R. Livingston, Jr., to John Jay

I most sincerely congratulate you upon our amazing success in Canada. If you knew the Obstacles we have had to struggle with you would think it little short of a miracle. Though as you will find by the letters you will receive herewith the matter is far from being ended, as the base desertion of the troops in the hour of victory, has left us much inferior to the enemy and I could wish that no attempt was made upon Quebec till the freezing of the lake admitted of our sending in a reinforcement, since there is no dependence to be placed upon the Canadians, & the first ill success will convert them into enemies, in which case with the assistance of Carleton we may be easily cut off.

But the people that compose our army think so much for themselves that no general dare oppose their sentiments if he was so inclined. You cannot conceive the trouble our generals have had, petition, mutinies & request to know the reason of every maneuver without a power to suspend or punish the offenders, the strongest proof of which is that Montgomery was under a necessity to reinstate Mott in order to quiet his men. Lamb is a good officer but so extremely turbulent that he excites infinite mischief in the army….

But my strongest objection was that your Committee is by no means adapted to the manners of the people with whom they are to deal & I am persuaded would not greatly raise the reputation of the congress, nor answer any good purpose among that polished people.

You brought us into this scrape, pray get us out, choose men who have the address to conciliate the affections of their fellow mortals, & send them up in February. I will accompany them in my private capacity, as I wish to make the jaunt.

Edited with commentary by Gordon Lloyd.

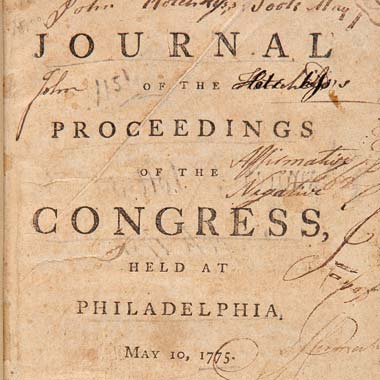

Journals of the Continental Congress

Journals of the Continental Congress