Second Continental Congress: February 13, 1776

February 13, 1776

Two new Committees are created and four existing Committees deliver reports. The committee to prepare an Address to the Inhabitants of these Colonies brought in a draft which was read and “Ordered, To lie on the table.” The main point of James Wilson’s Draft is to deny the claim by King and Parliament that Independence is the aim of the colonists. Yet the draft ends by preparing them for the possibility of independence: “That the Colonies may continue connected, as they have been, with Britain is our second Wish: Our first is–That America may be free.” John Adams’s position is to “preserve the Union.” Thomas Nelson remarks that “Independence, Confederation & foreign alliance are as formidable to some of the Congress, I fear to a majority.” These subjects have been but gently “touched upon.” But they should be! John Adams is more in tune with Patrick Henry than with John Dickinson.

Link to date-related documents.

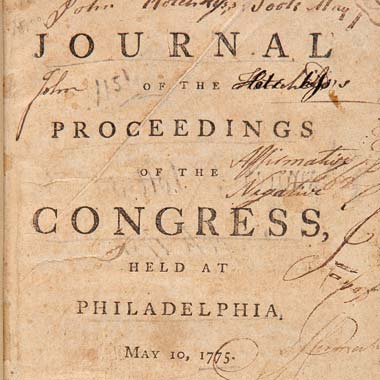

Journals of the Continental Congress [Edited]

Sundry letters were presented, read, and sent to a committee of three: Richard Smith, Josiah Bartlett, and [ ? ] Adams.

Letters and enclosures from the Convention of New Jersey were referred to the Indian Affairs Committee, Middle Department.

Resolved several financial, accommodation, and supply issues dealing with troops and the war effort.

The committee on the petition of Stacey Hepburn to trade with Hispaniola, brought in their report, which was agreed to.

The Committee appointed to prepare a resolution for the exportation of naval stores, presented their recommendation which was agreed to.

Congress addressed the pay and appointments of six battalions of troops in Virginia. Patrick Henry, was elected Colonel of the first battalion.

A committee of five–Thomas Lynch, James Wilson, John Penn, Benjamin Harrison, and Robert Alexander—were appointed to “consider into what departments the middle and southern colonies ought to be formed, in order that the military operations of the colonies may be carried on in a regular and systematic manner.”

Resolved, That Thomas Mc’Kean request that the committee of inspection restrain in passing censures on the venders of tea, till further orders from Congress.

Resolved, That the detachments marching from Philadelphia to New York, under the command of Colonel Dickinson, “receive the same pay as the four Pennsylvania battalions.” And that a committee of three– Roger Sherman, James Duane, and James Wilson–“consider the best method of subsisting the troops in New York, and what sum of money it will be necessary to send thither, and what sum ought to be advanced to Colonel Dickinson.”

The committee appointed to prepare an Address to the Inhabitants of these Colonies, brought in a draft, which was read and “Ordered, To lie on the table.”

Adjourned to 10 o’Clock tomorrow.

[Editor’s Note. John Dickinson wrote the First Draft of the Address. The Second Draft was written by James Wilson. The point of departure is the same: the accusation in the King’s Speech that the colonists were calling for independence was false. Both Dickinson and Wilson argued that the colonists were defending themselves and the British constitutional system grounded in Magna Carta, the 1628 Petition, the 1688 Bill of Rights, and the colonial heritage of constitutional self-government. They argued that this heritage was under attack by the current King and Parliament and the United Colonies were acting in self-defense. Wilson, however, went beyond Dickinson. In the final paragraph of the Second Draft of the Address, he prepares the Inhabitants of the Colonies to move from petition within the system to declaring separation from the existing system]

James Wilson’s Draft of an Address to the Inhabitants of these Colonies [Edited]

History, we believe, cannot furnish an Example of a Trust, higher and more important than that, which we have received from your Hands. It comprehends in it every Thing that can rouse the Attention and interest the Passions of a People, who will not reflect Disgrace upon their Ancestors nor degrade themselves, nor transmit Infamy to their Descendants. It is committed to us at a Time when every Thing dear and valuable to such a People is in imminent Danger. This Danger arises from those, whom we have been accustomed to consider as our Friends; who really were so, while they continued friendly to themselves; and who will again be so, when they shall return to a just Sense of their own Interests. The Calamities, which threaten us, would be attended with the total Loss of those Constitutions, formed upon the venerable Model of British Liberty, which have been long our Pride and Felicity. To avert those Calamities we are under the disagreeable Necessity of making temporary Deviations from those Constitutions….

That all Power was originally in the People–that all the Powers of Government are derived from them–that all Power, which they have not disposed of, still continues theirs–are Maxims of the English Constitution, which, we presume, will not be disputed. The Share of Power, which the King derives from the People, or, in other Words, the Prerogative of the Crown, is well known and precisely ascertained: It is the same in Great Britain and in the Colonies. The Share of Power, which the House of Commons derives from the People, is likewise well known: The Manner in which it is conveyed is by Election. But the House of Commons is not elected by the Colonists; and therefore, from them that Body can derive no Authority.

Besides; the Powers, which the House of Commons receives from its Constituents, are entrusted by the Colonies to their Assemblies in the several Provinces. Those Assemblies have Authority to propose and assent to Laws for the Government of their Electors, in the same Manner as the House of Commons has Authority to propose and assent to Laws for the Government of the Inhabitants of Great Britain. Now the same collective Body cannot delegate the same Powers to distinct representative Bodies. The undeniable Result is, that the House of Commons neither has nor can have any Power derived from the Inhabitants of these Colonies.

In the Instance of levying imposing Taxes, this Doctrine is clear and familiar: It is true and just in every other Instance. If it would be incongruous and absurd, that the same Property should be liable to be taxed by two Bodies independent of each other; would less Incongruity and Absurdity ensue, if the same Offence were to be subjected to different and perhaps inconsistent Punishments? Suppose the Punishment directed by the Laws of one Body to be Death, and that directed by those of the other Body be Banishment for Life; how could both Punishments be inflicted?

Though the Crown possesses the same Prerogative over the Colonies, which it possesses over the Inhabitants of Great Britain: Though the Colonists delegate to their Assemblies the same Powers which our Fellow Subjects in Britain delegate to the House of Commons: Yet by some inexplicable Mystery in Politics, which is the Foundation of the odious System that we have so much Reason to deplore, additional Powers over you are ascribed to the Crown, as a Branch of the British Legislature: And the House of Commons–a Body which acts solely by derivative Authority–is supposed entitled to exert over you an Authority, which you cannot give, and which it cannot receive.

The Sentence of universal Slavery gone forth against you is that the British Parliament have Power to make Laws, without your Consent, binding you in All Cases whatever. Your Fortunes, your Liberties, your Reputations, your Lives, every Thing that can render you and your Posterity happy, all are the Objects of the Laws: All must be enjoyed, impaired or destroyed as the Laws direct. And are you the Wretches, who have Nothing that you can or ought to call your own? Were all the rich Blessings of Nature, all the Bounties of indulgent Providence poured upon you, not for your own Use; but for the Use of those, upon whom neither Nature nor Providence hath bestowed Qualities or Advantages superior to yours?…

The Colonies, wearied with presenting fruitless Supplications and Petitions separately, or prevented, by arbitrary and abrupt Dissolutions of their Assemblies, from using even those fruitless Expedients for Redress, determined to join their Counsels and their Efforts. Many of the Injuries flowing from the unconstitutional and ill-advised Acts of the British Legislature, affected all the Provinces equally; and even in these Cases, in which the Injuries were confined, by the Acts, to one or to a few, the Principles, on which they were made, extended to all. If common Rights, common Interests, common Dangers and common Sufferings are Principles of Union, what could be more natural than the Union of the Colonies?

Delegates authorized by the several Provinces from Nova Scotia to Georgia to represent them and act in their Behalf, met in General Congress.

It has been objected, that this Measure was unknown to the Constitution; that the Congress was, of Consequence, an illegal Body; and that its Proceedings could not, in any Manner, be recognized by the Government of Britain. To those, who offer this Objection, and have attempted to vindicate, by its supposed Validity, the Neglect and Contempt, with which the Petition of that Congress to his Majesty was treated by the Ministry, we beg Leave, in our Turn, to propose, that they would explain the Principles of the Constitution, which warranted the Assembly of the Barons at Runnymede, when Magna Charta was signed, the Convention-Parliament that recalled Charles 2d, and the Convention of Lords and Commons that placed King William on the Throne. When they shall have done this, we shall perhaps, be able to apply their Principles to prove the Necessity and Propriety of a Congress.

But the Objections of those, who have done so much and aimed so much against the Liberties of America, are not confined to the Meeting and the Authority of the Congress: They are urged with equal Warmth against the Views and Inclinations of those who composed it. We are told, in the Name of Majesty itself, “that the Authors and Promoters of this desperate Conspiracy,” as those who framed his Majesty’s Speech are pleased to term our laudable Resistance; “have, in the Conduct of it, derived great Advantage from the Difference of his Majesty’s Intentions and theirs. That they meant only to amuse by vague Expressions of Attachment to the Parent State, and the strongest Protestations of Loyalty to the King, whilst they were preparing for a general Revolt. That on the Part of his Majesty and the Parliament, the Wish was rather to reclaim than to subdue.” It affords us some Pleasure to find that the Protestations of Loyalty to his Majesty, which have been made, are allowed to be strong; and that Attachment to the Parent State is owned to be expressed. Those Protestations of Loyalty and Expressions of Attachment ought, by every Rule of Candor, to be presumed to be sincere, unless Proofs evincing their Insincerity can be drawn from the Conduct of those who used them….

The Sentiments of the Colonies, expressed in the Proceedings of their Delegates assembled in 1774 were far from being disloyal or disrespectful. Was it disloyal to offer a Petition to your Sovereign? Did your anxious Impatience for an Answer, which your Hopes, founded only on your Wishes, as you too soon experienced, flattered you would be a gracious one–did this Impatience indicate a Disposition only to amuse? Did the keen Anguish, with which the Fate of the Petition filled your Breasts, betray an Inclination to avail yourselves of the Indignity with which you were treated, for forwarding favorite Designs of Revolt?

Was the Agreement not to import Merchandise from Great Britain or Ireland; nor after the tenth Day of September last, to export our Produce to those Kingdoms and the West Indies–was this a disrespectful or an hostile Measure? Surely we have a Right to withdraw or to continue our own Commerce. Though the British Parliament have exercised a Power of directing and restraining our Trade; yet, among all their extraordinary Pretensions, we recollect no Instance of their attempting to force it contrary to our Inclinations. It was well known, before this Measure was adopted, that it would be detrimental to our own Interest, as well as to that of our fellow-Subjects. We deplored it on both Accounts. We deplored the Necessity that produced it. But we were willing to sacrifice our Interest to any probable Method of regaining the Enjoyment of those Rights, which, by Violence and Injustice, had been infringed….

The humble unaspiring Colonists asked only for “Peace, Liberty and Safety.” This, we think, was a reasonable Request: Reasonable as it was, it has been refused. Our ministerial Foes, dreading the Effects, which our commercial Opposition might have upon their favorite Plan of reducing the Colonies to Slavery, were determined not to hazard it upon that Issue. They employed military Force to carry it into Execution. Opposition of Force by Force, or unlimited Subjection was now our only Alternative. Which of them did it become Freemen determined never to surrender that Character, to choose? The Choice was worthily made. We wish for Peace–we wish for Safety: But we will not, to obtain either or both of them, part with our Liberty. The sacred Gift descended to us from our Ancestors: We cannot dispose of it: We are bound by the strongest Ties to transmit it, as we have received it, pure and inviolate to our Posterity.

We have taken up Arms in the best of Causes. We have adhered to the virtuous Principles of our Ancestors, who expressly stipulated, in their Favor, and in ours, a Right to resist every Attempt upon their Liberties. We have complied with our Engagements to our Sovereign. He should be the Ruler of a free People: We will not, as far as his Character depends upon us, permit him to be degraded into a Tyrant over Slaves….

Possessed of so many Advantages; favored with the Prospect of so many more; Threatened with the Destruction of our constitutional Rights; cruelly and illiberally attacked, because we will not subscribe to our own Slavery; ought we to be animated with Vigor, or to sink into Despondency? When the Forms of our Governments are, by those entrusted with the Direction of them, perverted from their original Design; ought we to submit to this Perversion? Ought we to sacrifice the Forms, when the Sacrifice becomes necessary for preserving the Spirit of our Constitution? Or ought we to neglect and neglecting, to lose the Spirit by a superstitious Veneration for the Forms? We regard those Forms, and wish to preserve them as long as we can consistently with higher Objects: But much more do we regard essential Liberty, which, at all Events, we are determined not to lose, but with our Lives. In contending for this Liberty, we are willing to go through good Report, and through evil Report.

In our present Situation, in which we are called to oppose an Attack upon your Liberties, made under bold Pretensions of Authority from that Power, to which the executive Part of Government is, in the ordinary Course of Affairs, committed–in this Situation, every Mode of Resistance, though directed by Necessity and by Prudence, and authorized by the Spirit of the Constitution, will be exposed to plausible Objections drawn from its Forms. Concerning such Objections, and the Weight that may be allowed to them, we are little solicitous. It will not discourage us to find ourselves represented as “laboring to enflame the Minds of the People in America, and openly avowing Revolt, Hostility and Rebellion.” We deem it an Honor to “have raised Troops, and collected a naval Force”; and, clothed with the sacred Authority of the People, from whom all legitimate Authority proceeds “to have exercised legislative, executive and judicial Powers.” For what Purposes were those Powers instituted? For your Safety and Happiness. You and the World will judge whether those Purposes have been best promoted by us; or by those who claim the Powers, which they charge us with assuming.

But while we feel no Mortification at being misrepresented with Regard to the Measures employed by us for accomplishing the great Ends, which you have appointed us to pursue; we cannot sit easy under an Accusation, which charges us with laying aside those Ends, and endeavoring to accomplish such as are very different. We are accused of carrying on the War “for the Purpose of establishing an independent Empire.”

We disavow the Intention. We declare, that what we aim at, and what we are entrusted by our Constituents you to pursue, is the Defense and the Re-establishment of the constitutional Rights of the Colonies. Whoever gives impartial Attention to the Facts, we have already stated, and to the Observations we have already made, must be fully convinced that all the Steps, which have been taken by us in this unfortunate, Struggle, can be accounted for as rationally and as satisfactorily by supposing that the Defense and Re-establishment of their Rights were the Objects which the Colonists and their Representatives had in View; as by supposing that an independent Empire was their Aim….

Is no regard to be had to the Professions and Protestations made by us, on so many different Occasions, of Attachment to Great Britain of Allegiance to his Majesty; and of Submission to his Government upon the Terms, on which the Constitution points it out as a Duty, and on which alone a British Sovereign has a Right to demand it?

When the Hostilities commenced by the ministerial Forces in Massachusetts Bay, and the imminent Dangers threatening the other Colonies rendered it absolutely necessary that they should be put into a State of Defense–even on that Occasion, we did not forget our Duty to his Majesty, and our Regard for our fellow Subjects in Britain. Our Words are these: “But as we most ardently wish for a Restoration of the Harmony formerly subsisting between our Mother-Country and these Colonies, the Interruption of which must at all Events, be exceedingly injurious to both Countries: Resolved, that with a sincere Design of contributing, by all Means in our Power, not incompatible with a just Regard for the undoubted Rights and true Interests of these Colonies, to the Promotion of this most desirable Reconciliation, an humble and dutiful Address be presented to his Majesty.”

If Purposes of establishing an independent Empire has lurked in our Breasts, no fitter Occasion could have been found for giving Intimations of them, than in our Declaration setting forth the Causes and Necessity of our taking up Arms. Yet even there no Pretense can be found for fixing such an Imputation on us. “Lest this Declaration should disquiet the Minds of our Friends and fellow Subjects in any Part of the Empire, we assure them that we mean not to dissolve that Union, which has so long and so happily subsisted between us, and which we sincerely wish to see restored. Necessity has not yet driven us into that desperate Measure, or induced us to excite any other Nation to war against them. We have not raised Armies with the ambitious Designs of separating from Great Britain, and establishing independent States.” Our Petition to the King has the following Asseveration: “By such Arrangements as your Majesty’s Wisdom can form for collecting the united Sense of your American People, we are convinced your Majesty would receive such satisfactory Proofs of the Disposition of the Colonists towards their Sovereign and the Parent State, that the wished for Opportunity would be soon restored to them, of evincing the Sincerity of their Professions by every Testimony of Devotion becoming the most dutiful Subjects and the most affectionate Colonists.” In our Address to the Inhabitants of Great Britain, we say: “We are accused of aiming at Independence: But how is this Accusation supported? By the Allegations of your Ministers, not by our Actions. Give us Leave, most solemnly to assure you, that we have not yet lost Sight of the Object we have ever had in View, a Reconciliation with you on constitutional Principles, and a Restoration of that friendly Intercourse, which to the Advantage of both we till lately maintained.”

If we wished to detach you from your Allegiance to his Majesty, and to wean your Affections from a Connection with your fellow-Subjects in Great Britain, is it likely that we would take so much Pains, upon every proper Occasion, to place those Objects before you in the most agreeable Points of View?

If any equitable Terms of Accommodation had been offered us, and we had rejected them, there would have been some Foundation for the Charge that we endeavored to establish an independent Empire. But no Means have been used either by Parliament or by Administration for the Purpose of bringing this Contest to a Conclusion besides Penalties directed by Statutes, or Devastations occasioned by War. Alas! how long will Britons forget that Kindred-Blood flows in your Veins? How long will they strive, with hostile Fury to sluice it out from Bosoms that have already bled in their Cause; and, in their Cause, would still be willing to pour out what remains, to the last precious Drop?….

Britain and these Colonies have been Blessings to each other. Sure we are, that they might continue to be so. Some salutary System might certainly be devised, which would remove from both Sides, Jealousies that are ill-founded, and the Causes of Jealousies that are well-founded; which would restore to both Countries those important Benefits that Nature seems to have intended them reciprocally to confer and to receive; and which would secure the Continuance and the increase of those Benefits to numerous succeeding Generations. That such a System may be formed is our ardent Wish.

But as such a System must affect the Interest of the Colonies as much as that of the Mother-Country, why should the Colonies be excluded from a Voice in it? Should not, to say the least upon this Subject, their Consent be asked and obtained as to the general Ends, which it ought to be calculated to answer? Why should not its Validity depend upon us as well as upon the Inhabitants of Great Britain? No Disadvantage will result to them: An important Advantage will result to [us]. We shall be affected by no Laws, the Authority of which, as far as they regard us, is not founded on our own Consent. This Consent may be expressed as well by a solemn Compact, as if the Colonists, by their Representatives, had an immediate Voice in passing the Laws. In a Compact we would concede liberally to Parliament: For the Bounds of our Concessions would be known.

We are too much attached to the English Laws and Constitution, and know too well their happy Tendency to diffuse Freedom, Prosperity and Peace wherever they prevail, to desire an independent Empire. If one Part of the Constitution be pulled down, it is impossible to foretell whether the other Parts of it may not be shaken, and, perhaps overthrown. It is a Part of our Constitution to be under Allegiance to the Crown, Limited and ascertained as the Prerogative is, the Position–that a King can do no wrong–may be founded in Fact as well as in Law, if you are not wanting to yourselves.

We trace your Calamities to the House of Commons. They have undertaken to give and grant your Money. From a supposed virtual Representation in their House it is argued, that you ought to be bound by the Acts of the British Parliament in all Cases whatever. This is no Part of the Constitution. This is the Doctrine, to which we will never subscribe our Assent: This is the Claim, to which we adjure you, as you tender your own Freedom and Happiness, and the Freedom and Happiness of your Posterity, never to submit. The same Principles, which directed your Ancestors to oppose the exorbitant and dangerous Pretensions of the Crown, should direct you to oppose the no less exorbitant and dangerous Claims of the House of Commons….

While we shall be continued by you in the very important Trust, which you have committed to us, we shall keep our Eyes constantly and steadily fixed upon the Grand Object of the Union of the Co1onies–the Re-establishment and Security of their constitutional Rights. Every Measure that we employ shall be directed to the Attainment of this great End: No Measure, necessary, in our Opinion, for attaining it, shall be declined. If any such Measure should, against our principal Intention, draw the Colonies into Engagements that may suspend or dissolve their Union with their fellow-Subjects in Great Britain, we shall lament the Effect; but shall hold ourselves justified in adopting the Measure. That the Colonies may continue connected, as they have been, with Britain is our second Wish: Our first is–That America may be free.

John Adams to Abigail Adams

Mr. Dickinson’s Alacrity and Spirit upon this occasion, which certainly becomes his Character and sets a fine Example, is much talked of and applauded. This afternoon, the four Battalions of the Militia were together, and Mr. Dickinson mounted the Rostrum to harangue them, which he did with great Vehemence and Pathos, as it is reported….

In the Beginning of a War, in Colonies like this and Virginia, where the martial Spirit is but just awakened and the People are unaccustomed to Arms, it may be proper and necessary for such popular Orators as Henry and Dickinson to assume a military Character. But I really think them both, better Statesmen than Soldiers, though I cannot say they are not very good in the latter Character. Henry’s Principles, and Systems, are much more conformable to mine than the others however….

I am too old, and too much worn, with Fatigues of Study in my youth, and there is too little need in my Province of such assistance, for me to assume an Uniform. Non tali Auxilio nec Defensoribus istis Tempus eget. [Editor’s Note. This time doesn’t need such help and defenses as these. Aenid]

Thomas Nelson to John Page (Virginia Politician)

We laid the Virginia matters before Congress yesterday & supported them with all our powers; but they met with so strong an opposition from almost every Colony, that although they were deferred till today as a piece of respect, yet I am almost afraid I know their fate….[Editor’s Note. Contra Nelson’s expectations, Congress assumed the expenses of two Virginia battalions retroactively to November 1, 1775.]

I hope to have the pleasure of seeing you during the next Month, for I propose to get leave of absence for a few Weeks, that I may settlemy family & my affairs; the one driven from their place of residence since I left them & the other I had not time to adjust before I left Virginia having but a few days, after I left the service of the Convention at Richmond, before I set off for Philadelphia.

My request will not, I think be deemed unreasonable, after six Months absence, especially as the Colony will be represented & it is not imagined that matters of any great moment will come on before April, by which time I propose to return….[Editor’s Note. Nelson departed after Carter Braxton arrived on February 23]

Independence, Confederation & foreign alliance are as formidable to some of the Congress, I fear to a majority, as an apparition to a weak enervated Woman. These subjects have been but gently touched upon. Would you think that we have some among us, who still expect honorable proposals from administration? By Heavens I am an infidel in politics, for I do not believe were you to bid a thousand pound per scruple for Honor at the Court of Britain that you would get as many as would amount to an ounce. If Terms should be proposed they will savor so much of Despotism that America cannot accept them.

John Adams to John Trumbull (Governor of Connecticut)

Politics are a Labyrinth, without a Clue-to write upon that Subject would be endless. New York I think is now in a critical state, but I hope We Shall Save it. Mr Dickinson is to march at the Head of a Battalion of Philadelphian Associators to the Assistance of General Lee & Lord Sterling. He has this afternoon been haranguing the Battalions in the State House Yard with the Ardor and Pathos of a Grecian Commander, as it is reported….

If therefore the Colonies can be Secured against Corruption and Division I think with the Blessing of Heaven, they may hope to defend themselves. In all Events they will try the Experiment. Pray write me your Connecticut Politics. You mix the Caution and Jealousy of Athens with the Valor of Sparta. But don’t let your People forget or neglect to cultivate Harmony and preserve the Union.

Edited with commentary by Gordon Lloyd.

Journals of the Continental Congress

Journals of the Continental Congress