Second Continental Congress: January 3, 1776

January 3, 1776

Congress continues to be involved in the appointment of military leaders and the well-being of prisoners of war. Congress debates several Committee reports including the Report of the Committee on the unpatriotic behavior of the inhabitants of Queen’s County, New York in not sending deputies. Lord Drummond’s Plan of Accommodation and the status of reconciliation are discussed.

Link to date-related documents.

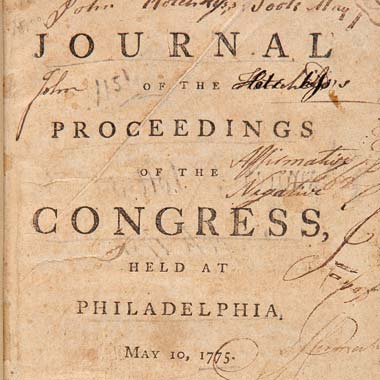

Journals of the Continental Congress [Edited]

A letter from General Washington, dated 25th December, inclosing a letter from General Howe with sundry papers, was laid before Congress, and read.

The Committee of Safety for Pennsylvania recommended field officers for the four battalions to be raised in Pennsylvania. Congress elected the colonels.

Congress, discussed the report of the Secret Committee.

Resolved, That specific goods and stores ought to be imported as soon as possible, for the use of the United Colonies.

Resolved, That the Secret Committee be empowered and directed to pursue the most effectual measures for importing the above articles.

Resolved, That the further consideration of this report be postponed.

The Committee of Claims reported, that there are claims due to two people.

Ordered, That the above be paid.

The Committee on the state of New York, brought in a further report, which was considered and agreed to.

Resolutions Based on the Committee Report on the state of New York [Edited]

Whereas a majority of the inhabitants of Queen’s County, in the colony of New York, being incapable of resolving to live and die freemen, and being more disposed to quit their liberties than part with the little proportion of their property necessary to defend them, have deserted the American cause, by refusing to send deputies as usual to the convention of that colony; and avowing by a public declaration, an unmanly design of remaining inactive spectators of the present contest, vainly flattering themselves, perhaps, that should Providence declare for our enemies, they may purchase their mercy and favor at an easy rate; and, on the other hand, if the war should terminate to the advantage of America, that then they may enjoy, without expense of blood or treasure, all the blessings resulting from that liberty, which they, in the day of trial, had abandoned, and in defense of which, many of their more virtuous neighbors and countrymen had nobly died:

And although the want of public spirit, observable in these men, rather excites pity than alarm, there being little danger to apprehend either from their prowess or example, yet it being reasonable, that those who refuse to defend their country, should be excluded from its protection, and be prevented from doing it injury:

Resolved, That all such persons in Queen’s county, aforesaid, as voted against sending deputies to the present convention of New York, and named in a list of delinquents in Queen’s county, published by the convention of New York, be put out of the protection of the United Colonies, and that all trade and intercourse with them cease; that none of the inhabitants of that county be permitted to travel or abide in any part of these United Colonies, out of their said county, without a certificate from the convention or committee of safety of the colony of New York, setting forth, that such inhabitant is a friend to the American cause, and not of the number of those who voted against sending deputies to the said convention; and that such of the said inhabitants as shall be found out of the said county, without such certificate, be apprehended and imprisoned for three months.

Resolved, That no attorney or lawyer ought to commence, prosecute, or defend any action at law, of any kind, for any of the said inhabitants of Queen’s county, who voted against sending deputies to the convention, as aforesaid; and such attorneys or lawyers as shall contravene this resolution, are enemies to the American cause, and ought to be treated accordingly.

Resolved, That the convention or committee of safety of New York be requested to continue publishing, for a month, in all their gazettes or newspapers, the names of all such of the inhabitants of Queen’s county, as voted against sending deputies; and to give certificates, in the manner before recommended, to such others of the said inhabitants, as are friends to American liberty.

And it is recommended to all conventions, committees of safety, and others, to be diligent in executing the above Resolutions.

Resolved, That Colonel Nathaniel Heard, of Woodbridge, in New Jersey, taking with him six hundred minute men, under discreet officers, march to the western part of Queen’s county, and that Colonel Waterbury, of Stanford, Connecticut, with the like number of minute men, march to the eastern side of said county; that they confer together, and endeavor to enter Queen’s county on the same day; that they proceed to disarm every person, who voted against sending deputies to the said convention, and cause them to deliver up their arms and ammunition on oath, and that they take and confine in safe custody, till further orders, all such as shall refuse compliance.

Resolved, That it be recommended Colonel Heard and Colonel Waterbury execute the business entrusted to them by the foregoing resolutions, with all possible dispatch, secrecy, order, and humanity.

Adjourned to 10 o’clock tomorrow.

Richard Smith’s Diary

I was on the Committee of Claims…. Col. Nat Heard of the Minute Men at Woodbridge & Col. Warterbury of Connecticut are ordered to take each a large Body of their Men & meet at a Day agreed on, in Queen’s County Long Island, & there disarm the Tories & secure the Ringleaders who it is said are provided with Arms & Ammunition from the Asia Man of War, & other Parts of the Report agreed to as was a Report from the Secret Committee….

Mr. Alexander from Maryland took his Seat….

Application was made from the Committee of Philadelphia asking Advice Whether to secure Lord Drummond and Andrew Elliot now in Philadelphia. Some Members gave them good political Characters & they remained unhurt.

Editor of the Journals of Congress on Lord Drummond’s Notes

Thomas Lundin, Lord Drummond (1742-80), was the central figure in what one historian has called “the last effort before the Declaration of Independence to reconcile the American colonies with Great Britain and prevent the disruption of the empire.” Born in Scotland, Drummond, whose father claimed the title of 10th earl of Perth, came to America in 1768 to oversee family lands in East Jersey. In America Drummond acquired many friends among the New York and New Jersey aristocracies and developed a sympathy for colonial grievances over the Townshend, Tea, and Coercive Acts. In the autumn of 1774, after adjournment of the First Continental Congress, he offered to present to the British government the views of certain moderate delegates who had expressed to him “their Readiness to contribute towards the general Support [of the empire] should such a mode be devised for the Completion of this Purpose as would give a Security against any further Invasion of their Property by Parliament.” Drummond never identified the delegates to whom he volunteered his services, but the views which he ascribed to them were remarkably similar to those expressed by James Duane. …

Drummond arrived in England in December 1774 and soon entered into conversations with Lord North and Lord Dartmouth. In March 1775 he drew up a “Plan of Accommodation” listing six points as bases for negotiations between America and Great Britain….

Drummond’s “Plan” called for colonial assemblies to provide the crown with “a perpetual Grant” of revenue derived from taxes on “such Articles . . . as they shall deem most likely to keep pace with the Growth or Decline of the said Colonies.” In return for this concession, he proposed that Parliament formally relinquish “all future Claim of Taxation” over the colonies and agree to apply revenue from American trade to “the Expenses of Collection,” with surpluses “to be subject to the disposal of the respective Houses of Assembly.” According to Drummond, this “Plan” was approved not only by North and Dartmouth but also by Chief Justice Mansfield and Sir Gilbert Elliot, the latter a Scottish MP who had been instrumental in persuading a skeptical House of Commons to pass North’s Conciliatory Resolve of February 20, 1775. At first Drummond intended to send a copy of the “Plan” to friends in America, but he was dissuaded by Elliot, who convinced him that negotiations were more likely to succeed if they were represented as originating in America. As a result Drummond left England in September 1775 and returned to America in the capacity of a private subject purporting unofficially to represent the views of the North ministry….

Late in December 1775 Drummond came to Philadelphia in the company of Andrew Elliot, the royal collector in New York and brother of Sir Gilbert. The Pennsylvania Committee of Safety was suspicious of their designs and asked Congress on January 3 if they should not be arrested. When Congress decided against this step, the committee exacted an oath from them not to reveal any information about Philadelphia’s defenses. Thereafter Drummond and Elliot began a series of conversations lasting through January 14 with a group of moderate delegates, chief among whom were Andrew Allen, James Duane, John Jay, William Livingston, and Thomas Lynch. They are also known to have spoken with Silas Deane, James Wilson, and Edward Rutledge, and to have been in indirect contact with John Hancock. In all this Drummond was careful to disclaim any official authorization from the British government, and the delegates made it clear that they were not treating in behalf of Congress.

During preliminary conversations Drummond sought to convince the delegates of the good intentions of the British government and in the process concluded that “the old Point of Taxation was still the Hinge on which the state of America was likely to turn.” He then informed them of his “Plan of Accommodation.” Initially the delegates were reluctant to assent to his proposal for a colonial grant of a perpetual revenue to the crown, but at length he overcame their doubts. Once agreement had been reached on this issue, the range of the talks broadened considerably, in the course of which the delegates agreed not to press their complaints about vice-admiralty court jurisdiction, the Statute of Treason passed during the reign of Henry VIII, or the Declaratory and Quebec Acts. These conversations also led to the formulation of a list of negotiating positions in which the delegates demanded such concessions as relinquishment of Parliament’s claim to a right to tax the colonies; freedom to manufacture and consume finished products made from colonial raw materials; inclusion of Canada “in the Indemnification;” appointment of provincial supreme court justices during good behavior; and the revision of the Navigation Acts. In return, they pledged to observe the Acts of Trade, to grant Great Britain a perpetual revenue, and to provide her with naval and military supplies, when “called upon in Cases of Urgency.” Finally, agreement was reached on a compromise plan for the government of Massachusetts, which, according to Drummond, was shown to and approved by John Hancock. Specific details about this plan are lacking, but Thomas Lynch insinuated that it envisioned either the return of the Bay Colony’s 1691 charter or concessions to the province in the form of an amendment to the Massachusetts Government Act of 1774.

The next problem was how to initiate formal negotiations between America and Great Britain. At first the delegates wanted Drummond and Elliot to open talks with the North ministry, but Drummond insisted that the cause of peace would be served best if Congress sent an official deputation. Although the delegates were cool to this idea, pointing out that they were subject to arrest for treason in the mother country, they agreed to a congressional peace delegation when Drummond consented to remain in America as a hostage.

Drummond subsequently maintained that at the conclusion of his talks with the delegates around January 14, “a very decided Majority of the Members of the Congress, representing not less than seven different Provinces,” favored negotiations along the lines described above. Whatever the accuracy of this claim, however owing to a variety of circumstances Congress never formally took up the question of sending a delegation to England. Thomas Lynch was on the verge of introducing this issue in Congress when news arrived on January 17 of the American defeat at Quebec on New Year’s Eve, which, combined with earlier intelligence about Lord Dunmore’s New Year’s Day attack on Norfolk, left Congress in no mood for conciliation. Early the next month Lynch and Andrew Allen took advantage of their appointment to a committee to confer with the New York Committee of Safety about the activities of General Charles Lee to meet again with Drummond, who meanwhile had returned to New York to promote peace negotiations. As a result of their conversation on February 5, Drummond wrote a letter to British General James Robertson in Boston, asking him to arrange passports for a congressional peace delegation. Lynch, in turn, sent Drummond’s letter to Washington, requesting the general to forward it to Robertson. Instead of complying with this request, however, Washington sent both Drummond’s and Lynch’s letters to Congress, where they arrived on February 29 and were considered in a committee of the whole on March 5.

Washington’s action could scarcely have come at a worse time for the proponents of reconciliation. Lynch was incapacitated by a stroke; Duane was compromised by the revelation of the treachery of his valet, James Brattle; and Jay was absent from Congress until March 2. In addition, the cause of reconciliation had been dealt a stunning blow by the arrival in Philadelphia on February 27 of news of the Prohibitory Act, which at one time both declared war on American commerce and held out the prospect of a royal peace commission. Even so, the delegates response to the intelligence from Washington revealed surprising support in Congress for negotiations, for although they commended Washington’s action, they simultaneously rejected motions by George Wythe to forbid anyone “other than the Congress or the People at large . . . to treat for Peace” and by William Livingston to bring Drummond to Philadelphia “to explain his Conduct.”

Nevertheless, the events of March 5 marked the effective end of the Drummond peace mission. For several months moderates continued to hope that Britain would send commissioners to America empowered to conclude terms similar to those promised by Drummond. Unfortunately for this hope, the Howe brothers’ commission did not become operative until two weeks after the Declaration of Independence, and its terms were disappointing.

Edited with commentary by Gordon Lloyd.

Journals of the Continental Congress

Journals of the Continental Congress