Second Continental Congress: July 25, 1775

July 25, 1775

Several Committees deliver their Reports and Congress continues to be heavily involved in the personnel, ammunition, and financial aspects of the war effort. “As the signing so great a number of [money]bills … will take more time than the members can possibly devote,” Congress Resolved that [30] persons be “authorized to sign the same.” Among those selected was William Jackson who would become the Secretary at the Constitutional Convention.

Congress resumes the paragraph by paragraph debate of the Address to the Assembly of Jamaica, which was agreed to.

Link to date-related documents.

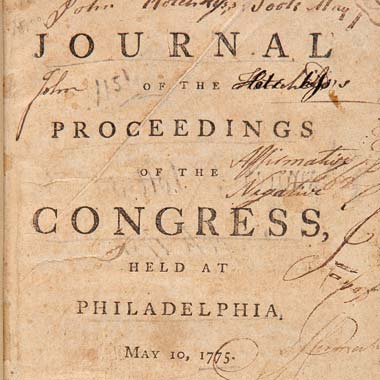

Journals of the Continental Congress [Edited]

The Committee for establishing a hospital entered their report which was read.

The Committee appointed to consider the ways and means of establishing posts, brought in their report, which was read, and ordered to be taken into consideration tomorrow.

The Committee appointed to bring in an answer to the resolution of the house of Commons, brought in their report, which was read, and ordered to lie on the table for consideration.

The Congress being informed that a quantity of the Continental gunpowder, amounting to about six tons and half, was arrived in this city,

Ordered, That the delegates of this colony take measures to have it sent under a safe convoy with all possible dispatch to General Washington at the Camp before Boston.

That the delegates be empowered to order a detachment of the riflemen raised for the continental army, consisting of at least two Officers and thirty men to meet the powder wagons at Trenton and from thence to escort the same to the camp.

The Congress then resumed the Consideration of the Address to the Assembly of Jamaica, which being debated by paragraphs, was agreed to and is as follows:

[Note from the Editors of the Journal: This address was not entered upon the Journals.]

The Address to the Assembly of Jamaica [Edited]

We would think ourselves deficient in our duty, if we suffered this Congress to pass over, without expressing our esteem for the assembly of Jamaica….

All the arts of sophistry were tried to show that the British ministry had by law a right to enslave us. The first and best maxims of the Constitution, venerable to Britons and to Americans, were perverted and profaned. The power of parliament, derived from the people, to bind the people, was extended over those from whom it was never derived. It is asserted that a standing army may be constitutionally kept among us, without our consent. Those principles, dishonorable to those who adopted them, and destructive to those to whom they were applied, were nevertheless carried into execution by the foes of liberty and of mankind. Acts of parliament, ruinous to America, and unserviceable to Britain, were made to bind us; armies, maintained by the parliament, were sent over to secure their operation. The power, however, and the cunning of our adversaries, were alike unsuccessful. We refused to their parliaments and obedience, which our judgments disapproved of: We refused to their armies a submission, which spirits unaccustomed to slavery, could not brook.

But while we spurned a disgraceful subjection, we were far from running into rash or seditious measures of opposition. Filled with sentiments of loyalty to our sovereign, and of affection and respect for our fellow subjects in Britain, we petitioned, we supplicated, we expostulated: Our prayers were rejected;–our remonstrances were disregarded;–our grievances were accumulated. All this did not provoke us to violence.

An appeal to the justice and humanity of those who had injured us, and who were bound to redress our injuries, was ineffectual: we next resolved to make an appeal to their interests, though by doing so, we knew we must sacrifice our own, and (which gave us equal uneasiness) that of our friends, who had never offended, us, and who were connected with us by a sympathy of feelings, under oppressions similar to our own. We resolved to give up our commerce that we might preserve our liberty. We flattered ourselves, that when, by withdrawing our commercial intercourse with Britain, which we had an undoubted right either to withdraw or continue, her trade should be diminished, her revenues impaired, and her manufactures unemployed, our ministerial foes would be induced by interest, or compelled by necessity, to depart from the plan of tyranny which they had so long pursued, and to substitute in its place, a system more compatible with the freedom of America, and justice of Britain. That this scheme of non-importation and non-exportation might be productive of the desired effects, we were obliged to include the islands in it. From this necessity, and from this necessity alone, has our conduct towards them proceeded. By converting your sugar plantations into fields of grain, you can supply yourselves with the necessaries of life: While the present unhappy struggle shall continue, we cannot do more.

But why should we make any apology to the patriotic assembly of Jamaica, who knows so well the value of liberty; who are so sensible of the extreme danger to which ours is exposed; and who foresee how certainly the destruction of ours must be followed by the destruction of their own?

We receive uncommon pleasure from observing the principles of our righteous opposition distinguished by your approbation: We feel the warmest gratitude for your pathetic mediation in our behalf with the crown. It was indeed unavailing–but are you to blame? Mournful experience tells us that petitions are often rejected, while the sentiments and conduct of the petitioners entitle what they offer to a happier fate.

That our petitions have been treated with disdain, is now become the smallest part of our complaint: Ministerial insolence is lost in ministerial barbarity. It has, by an exertion peculiarly ingenious, procured those very measures, which it laid us under the hard necessity of pursuing, to be stigmatized in parliament as rebellious: It has employed additional fleets and armies for the infamous purpose of compelling us to abandon them: It has plunged us in all the horrors and calamities of civil war: It has caused the treasure and blood of Britons (formerly shed and expended for far other ends) to be spilt and wasted in the execrable design of spreading slavery over British America: It will not, however, accomplish its aim: In the worst of contingencies, a choice will still be left, which it never can prevent us from making.

The peculiar situation of your island forbids your assistance. But we have your good wishes. From the good wishes of the friends of liberty and mankind, we shall always derive consolation.

Resolved, That Samuel Adams, Richard Henry Lee, and John Rutledge, with the Secretary, be a committee to revise the Journal of the Congress, and prepare it for the press.

Adjourned until tomorrow at 8 o’Clock.

Benjamin Harrison to George Washington

We Expect to leave this place next Sunday.

Edited with commentary by Gordon Lloyd.

Journals of the Continental Congress

Journals of the Continental Congress