The Six Stages of Ratification: Stage II

The Fall Campaign: Off to a Fast Start

Delaware—December 7, 1787

Pennsylvania—December 12, 1787

New Jersey—December 18 1787

Georgia—January 2, 1788

Connecticut—January 8, 1788

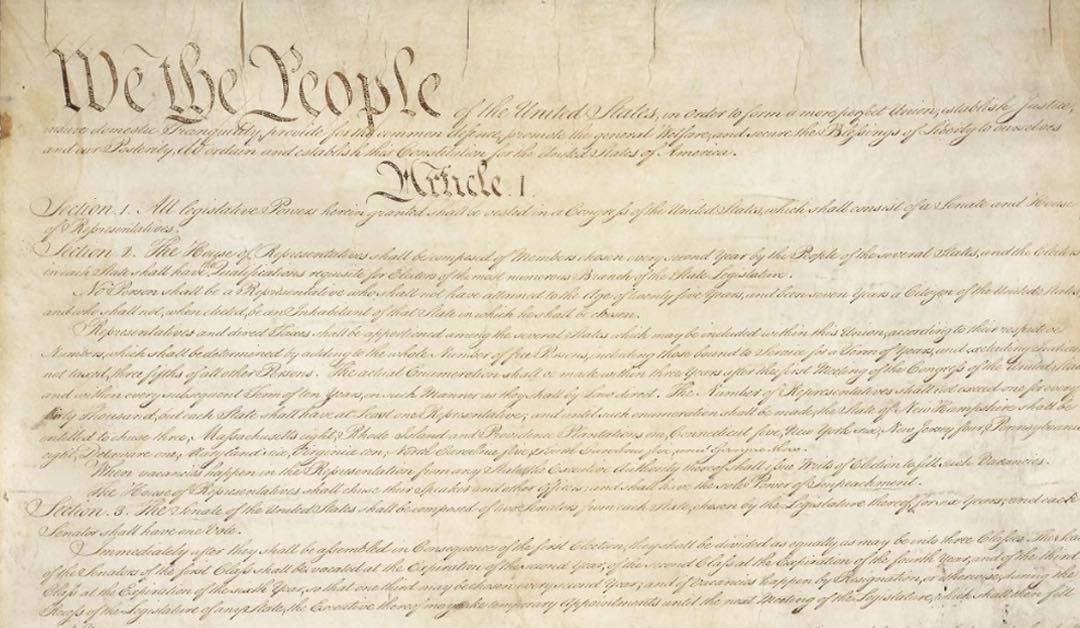

Introduction

The conceptual component of the Fall chronology is this: the Madisonians wanted to win big, win early, and gain momentum, thus making it difficult for subsequent ratifying conventions to vote against adoption of the Constitution. And that’s precisely what they accomplished. There was a very fast start in this Federalist–Antifederalist 5-0 sweep. The only objections that occur are in Pennsylvania and Connecticut. At the outset of the Pennsylvania ratifying convention, it was 46 to 23, coming out it was 46 to 23. In Connecticut, going in it was 128 to 40 and coming out it was 128 to 40. No one changed his mind. So the objectors went in objecting and nothing happened to change their mind. The 23 members of the Pennsylvania Minority expressed their views in the Pennsylvania Minority Report because the majority refused to include the objections in the official journal. The 40 in Connecticut didn’t file a minority report. So by the time we get around to the New Year in January 1788, the Madisonians have five states already ratifying the Constitution. They only need four more states and the Antifederalists need five. The initial bad news had been overcome; it looked like a shoe-in for the Federalists.

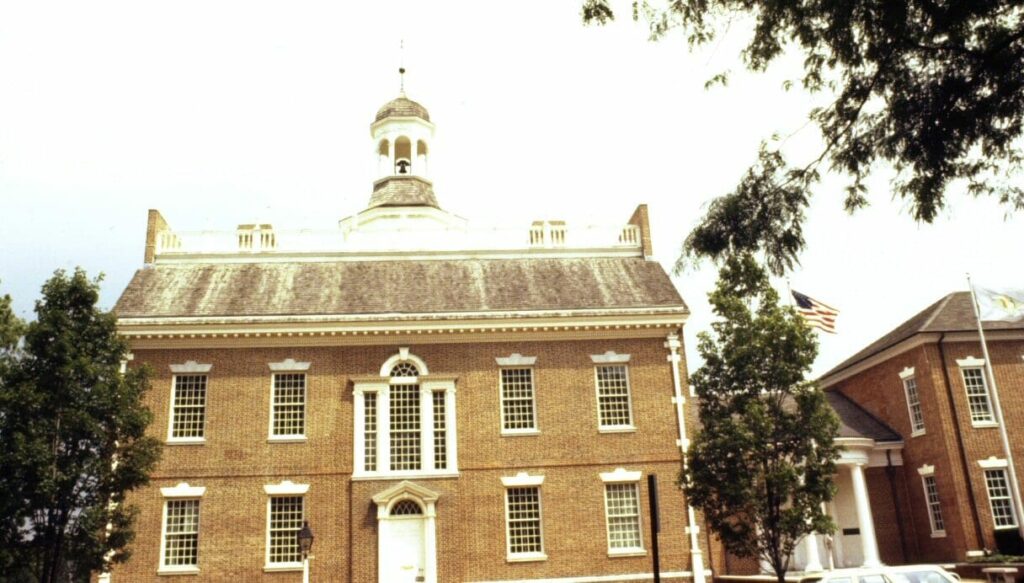

Delaware

The first state to ratify was Delaware. The Delaware legislature began its new session in October 1787 and by early November had called for elections for the state ratifying convention to be held on November 9 and 10. Ten members were to be elected from each of the three counties for a total of 30 delegates, the same number of representatives in the lower house of the Delaware legislature. And what we have called the Madison forces were out there in the electoral districts making sure that the pro-Constitutionalists were selected as delegates. No Antifederalists ran for election. Most importantly, Delaware voters selected Bedford and Bassett to the ratifying convention in Dover. Bedford and Bassett didn’t play major roles at the Philadelphia Convention; they were always over-shadowed by two other Delaware delegates, namely George Read and John Dickinson. But it turns out that, here, as elsewhere, some Framers whose role in the Constitutional Convention was limited, actually shined in the ratifying conventions.

Unfortunately, there is no record of the proceedings or significant correspondence that might illuminate what took place. It is clear, however, that Bedford and Bassett needed to do very little explaining because the 30 people who were elected were all Federalists, and all were in favor of adopting the Constitution before they even entered the ratifying convention. These 30 people showed up in Dover on December 4th, and these delegates representing the 60,000 people of Delaware had a momentous decision to make. Shall we or shall we not ratify this Constitution? Three days later, they ratified. There was not much conversation. They were all in agreement and they also behaved themselves. Not one deviated from what the voters understood when they were elected—I voted for you and you will vote for ratification. So Delaware, although the second state to convene, was the first to ratify. Now it might strike you as a little odd, given the conventional wisdom, that Delaware, the smallest state in the Union, had no objection to ratifying. There are all kinds of self-interested, even conspiratorial, theories that have circulated over the years to explain away this oddity including that Delaware ratified first in order to be favorably considered for federal grants.

Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania politics between 1776 and 1787 was divided roughly two to one between those who favored the Constitution and those who disliked the Constitution. This breakdown, however, was not manifested in either the election or the voting of the eight-member delegation to the Philadelphia Convention. All eight resided in Philadelphia and only Ben Franklin and Jarred Ingersoll demonstrated any reservations that the proposed Constitution might deviate from traditional teachings on federalism and republicanism. The division was present in the very 69 member unicameral Pennsylvania legislature that called for the ratifying convention. So it is no surprise that going into the Pennsylvania ratifying convention, there was a 46-23 divide among the elected delegates.

The in-doors and out-of-doors debate was dominated by James Wilson who had set the tone, not only for the Pennsylvania debate but for the whole country, with his State House Speech on October 6, 1787. Wilson responded to the objections recently published by fellow Philadelphia delegate George Mason who declined to sign the Constitution. There is no doubt that this speech played a major part in the ratification of the Constitution. Professor George Graham has marveled at Wilson‘s dramatic rhetorical brilliance and has gone so far as to call the speech a “kind of pre-emptive strike.” On the other hand, Jackson Turner Main, following the path introduced by Libby, points to the intractable differences between the cosmopolitan Federalists and the agrarian Antifederalists.

The ratifying convention met between November 21 and December 12 and, again, Wilson dominated the conversation. According to Wilson, the sole delegate to the Philadelphia Convention who ran for election to the state ratifying convention, there was no need for a bill of rights because under the proposed Constitution everything that is not delegated is reserved. Central to this “counter attack” was his contrasting the Preamble of the Constitution to the bills of rights attached to state constitutions.

After three weeks of non-debate during which no one changed his mind, the Constitution passed by a vote of 46-23. The 23 in the minority—the Pennsylvania Minority— requested that their objections be placed on the record. But the pro-Constitution Federalists said, “Absolutely not.”

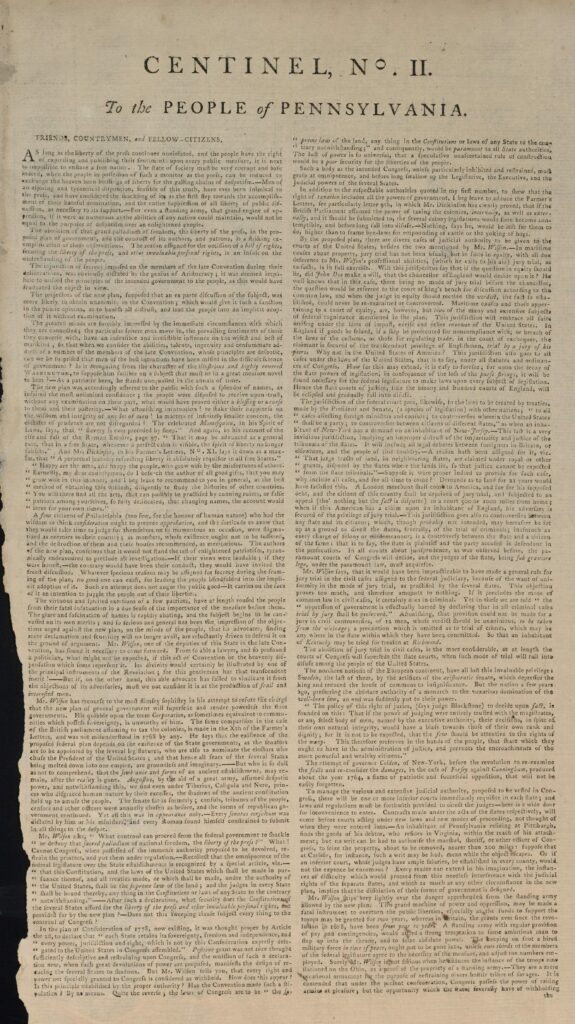

So the minority bought newspaper space and sent their objections out all over the nation. This became the Pennsylvania Minority Report, the report of these 23 elected delegates who had been refused by the dominant party to have their objections stated. This Report, in turn, was widely circulated up and down the country and while it did nothing to help the cause in Pennsylvania or the fall campaign, it did help in the winter and summer of 1788. Simultaneously, Pennsylvanian Samuel Bryan wrote the first of 18 Centinel essays criticizing the tendency of the proposed Constitution toward consolidated government. The Centinel essays were also influential in the out-of-doors pamphlet wars. The Antifederalists lost the battle in Pennsylvania, but they were preparing for the war that lay ahead.

New Jersey

On October 29, 1787, the New Jersey legislature unanimously called for a state ratifying convention. There were 13 counties in New Jersey and each chose three delegates to attend the ratifying convention. Elections were held between November 27 and December 1 and only Federalist delegates were elected. The little information about what took place has been compiled from local newspaper sources. They met on December 11 at Francis Witt’s Tavern and ratified the Constitution on December 20. One question seems to call for an explanation. Why did New Jersey, the state that gave us the New Jersey Plan at the Constitutional Convention in the summer of 1787 and whose delegates fought with the Madison forces in Philadelphia, ratify so quickly and easily? Richard McCormick and Jackson Turner Main have a ready-made economic answer: “It had a very large debt and had been obliged to levy heavy taxes on land. Were the Constitution adopted, the burden of much of this debt would be assumed by the central government.” But there is also a political answer: potential Antifederalist objections had been accommodated in the very Constitution itself as a result of the debates in Philadelphia during the summer of 1787.

Georgia

In October 1787, the Constitution was published in a Savannah newspaper and the Georgia Assembly called for the election of delegates to the ratifying Convention to take place in early December. It is unclear from the record whether 11 counties each elected three delegates, but only 29—all pro-Constitutional—participated. What is known is that on January 2, 1788, 26 delegates from 10 counties voted to ratify the Constitution. There was, not unsurprisingly, virtually no opposition to the Constitution in Georgia. What was surprising was that other than the reproduction of Wilson’s State House Speech and Centinel I, there was very little reporting of the robust pamphlet exchanges taking place elsewhere. Very little is known of the in-house discussion except that the delegates gathered on December 25, 1787, got down to business on December 28, ended their deliberations on December 31, and signed on January 2, 1788. Presumably, this ratifying convention did what all the other ratifying conventions did, namely, went through the Constitution paragraph by paragraph. A piece written by Joseph Habersham for a Savannah newspaper said that the “Constitution was read over Paragraph by Paragraph.” But there is no official record available of what took place.

But, and this will become a recurring question given what took place at the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia during the summer of 1787, why did Georgia ratify so quickly and overwhelmingly? George Washington and Samuel Bryan, author of the Centinel Antifederalist essays, at least agreed on one thing: the overriding critical nature of “the Indian Question.”

Connecticut

The Connecticut Assembly, on October 19, 1787, called for town meetings to take place on November 12 for the purpose of electing state ratifying delegates. The vote in favor of ratification in Connecticut on January 9, 1788 was 128-40. To some scholars—Christopher Collier and Jackson Turner Main come to mind—this overwhelming support in favor of the adoption of the Constitution was a great surprise and suggested that the Antifederalists didn’t have “a fair chance.” After all, in February 1787, Connecticut was the only state in the Confederation Congress to vote against endorsing the call for a Grand Convention in Philadelphia. Perhaps, Collier suggests, this rapid turnaround is due to deceit, propaganda, and suppression of information. There is a good possibility, he concludes, that the majority of Connecticut voters were Antifederalists and that they were hoodwinked to adopt a government as restrictive as they had endured under British rule. Similarly, Main remarks that “the prejudice of the newspapers which greatly injured the Antifederalists.”

But one should not underestimate the extent to which the Connecticut delegates to the Philadelphia Convention had been genuinely accommodated. They were the authors of the Connecticut Compromise which they considered to be actually a Connecticut Principle. And if they couldn’t persuade the delegates to go along with the Connecticut Compromise, and thus the Constitution itself, they weren’t very good at all. In fact, Sherman, Ellsworth, and Johnson were in the Connecticut ratifying convention defending the Constitution just as they had been defending it in the out-of-doors pamphlet war.