The Six Stages of Ratification: Stage IV

Springtime in the Middle States: And Then There Was One Pillar to Go

Maryland April 28, 1788

South Carolina May 23, 1788

Introduction

Would springtime add momentum to the emerging Antifederalist challenge fueled in large part by the out-of-doors pamphlet literature and the impressive showings in New Hampshire and Massachusetts? Or were their days in the snow of New England merely a “one-off” success in terms of electoral politics?

Given the concerns expressed by the delegates from Maryland and South Carolina at the Philadelphia Convention, one might anticipate that there would be quite a confrontation in Maryland and South Carolina. But the delegates from these two states adopted the Constitution very easily: 63 to 11, and 149 to 73, respectively. More importantly, these “exit votes” were virtually the same as the “entrance votes” going in to the ratifying conventions. Moreover, there wasn’t much of a debate despite the official declarations that the proposed Constitution had been “fully considered.” The problem is that we will never know why Maryland and South Carolina didn’t put up much of an opposition. The official records are very sparse. We can only speculate as to why the Antifederalists failed to mount a credible challenge at this stage of ratification. Jackson Turner Main puts it down to a biased press and the location of the state ratifying conventions.

Maryland

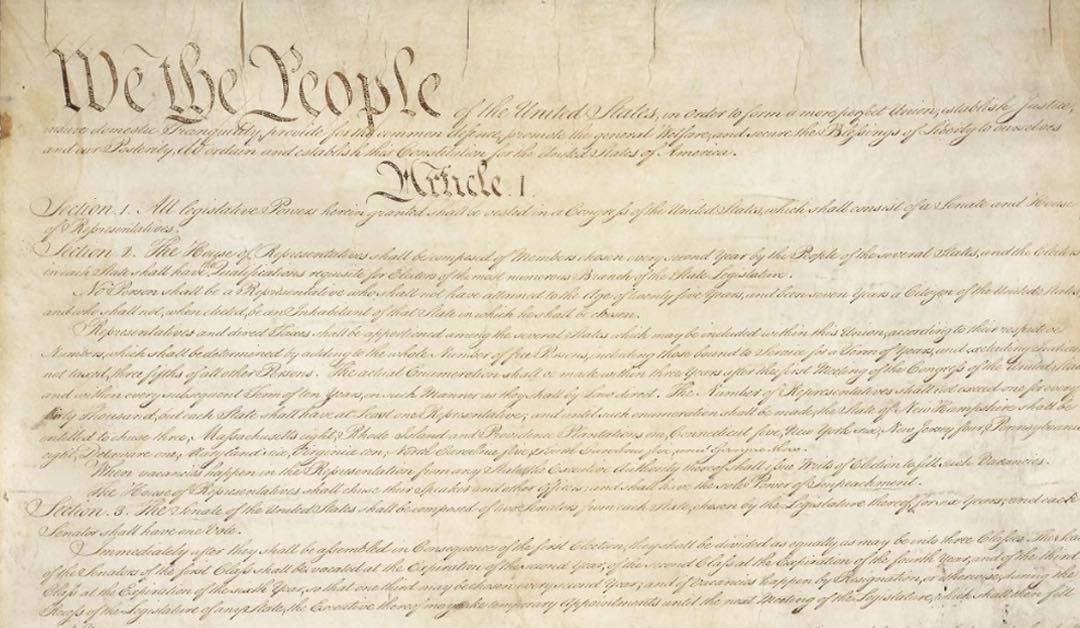

Maryland Statehouse, Site of the Maryland Ratifying Convention

Of considerable interest—and this has not been effectively addressed—is the question: why didn’t the Antifederalists put up much of a fight in Maryland, the last state to ratify the Articles of Confederation and the home of Luther Martin and John Mercer who left the Philadelphia Convention early in order to mount a formidable challenge to ratification? James McHenry, one of three Maryland delegates to sign the Constitution on September 17, 1787, informed his Federalist allies across the country that he was concerned about the ratification struggle because Martin and Mercer had been elected to the ratifying convention. And ratifying convention delegates William Paca and Samuel Clark—who had expressed concern about the absence of a bill of rights in the proposed Constitution—were powerful politicians.

A leading commentator on the Maryland ratifying convention, Gregory Stiverson, argues that less than a quarter of the electorate voted, that there were some suspicious electoral recordings, Paca cut a deal with the Federalists, and Luther Martin had a sore throat. That is why the Antifederalists were ineffective in Maryland, namely, some sort of undemocratic political activity took place by the aristocratic Federalists.

South Carolina

South Carolina met on Monday, May 19 and, according to the official recorder, “continued by divers adjournments to Friday, the 23rd of May.” Thomas Pinckney, the President of the convention, declared the Constitution ratified in South Carolina after the delegates had “maturely considered the Constitution.” Now Pinckney did go on to assert the need to recognize a bill of rights. A historian of the South Carolina state ratifying convention, Jerome Nadelhaft, suggests that there was inappropriate electoral behavior by Federalists in South Carolina. According to Nadelhaft, the Federalists wined, dined, flattered, and cajoled the delegates. More importantly, he suggests that the whole process was possibly undemocratic. “The delegates opposed to the Constitution, however, probably represented a majority of the state population, and Antifederalism was stronger in the state at large than the ratification vote indicated.”