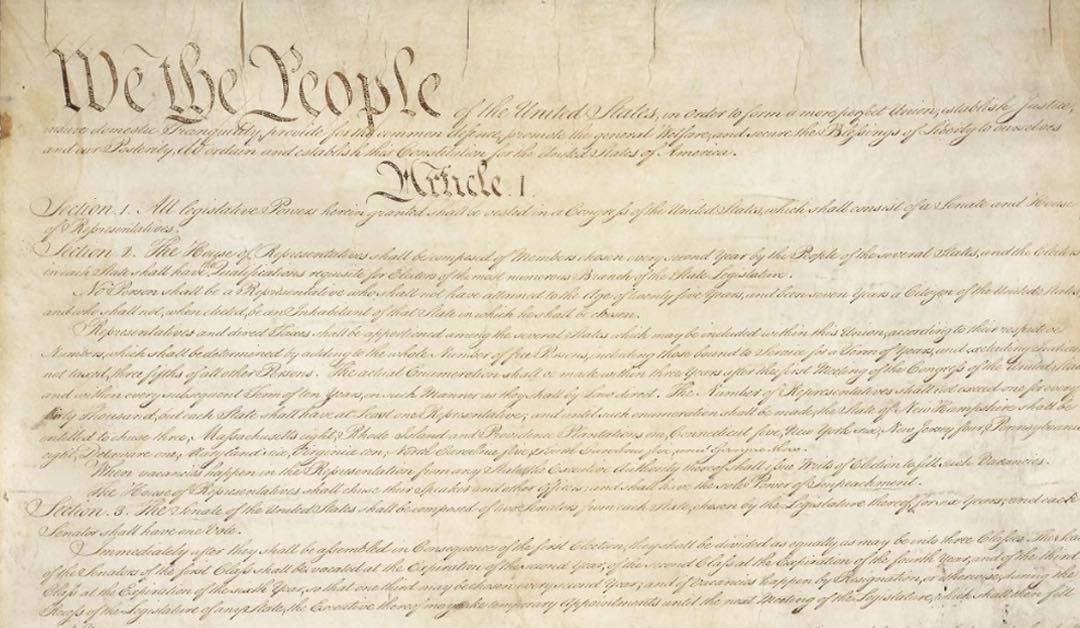

The Six Stages of Ratification: Stage V

A Long Hot Summer: Nail Biting Time

New Hampshire June 21, 1788

Virginia June 26, 1788

New York July 26, 1788

Introduction

The fate of the Constitution virtually hung in the balance during the summer of 1788. While it was true that Madison only needed the affirmative vote of one of those three state ratifying conventions and the Antifederalists needed all three, if you look at the predicted vote going in, then it was clear that Madison had some very real problems. New Hampshire was 52-52, Virginia was 84-84, and New York was 19 in favor and 46 against by what today we might call “entrance polls.” It was going to be an extremely close call.

I suggest that the agreement in Massachusetts laid the foundation for the resolution of this dramatic and vital summer stage. The “ratify now, amend later” compromise overcame the immediate crisis in Massachusetts, but more importantly the agreement provided the nation with a model for breaking subsequent crises. So, in New Hampshire, what broke the crisis? The Massachusetts Compromise. Five people changed their minds and 12 amendments were proposed. In Virginia, what broke the crisis? The Massachusetts Compromise. Five delegates changed their minds. Twenty amendments were proposed and also 20 items constituting a bill of rights.

By the end of May 1788, proponents of the Constitution had secured the approval of eight state ratifying conventions. Along the way, however, they made a critical tactical decision and an important, albeit non-binding, concession in order to deny the Antifederalists their first victory. In New Hampshire, facing sure defeat, the proponents secured an agreement at the ratifying convention to postpone a final decision, consult with the voters, hold a second election, and reconvene four months later. In Massachusetts, also in February, 10 delegates abandoned their opposition to ratification in exchange for the proposition that “subsequent amendments” would be considered in the First Congress. This Massachusetts Compromise proposal —“ratify now, amend later”—moved an equally divided Convention to adopt the Constitution.

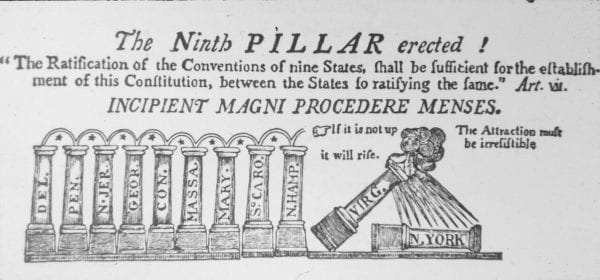

Securing the ninth state was not going to be an easy task. In fact, North Carolina and Rhode Island did not ratify the Constitution until November 1789 and May 1790, respectively. They did so only after the First Congress sent 12 amendment proposals to the states for ratification. Everything rested on the three remaining states: New Hampshire, Virginia, and New York. The best evidence suggests that going into the three ratifying conventions, the Federalist–Antifederalist delegate split was 52-52 in New Hampshire, 84-84 in Virginia, and 19-46 in New York. All were scheduled to meet in June: Virginia on the 2nd, New York on the 17th, and New Hampshire on the 18th.

New Hampshire

In preparation for the June New Hampshire ratifying convention, the Federalist leaders were far more active in their campaigning than in February. Even then, it turned out that the vote was virtually even going into the convention. It turns out, furthermore, that five delegates adopted the Massachusetts Compromise in New Hampshire after three days of debate. Thus the Constitution was officially ratified on June 21, 1788 by a vote of 57-47. According to Jere Daniell, only calculated and manipulative political maneuvering by Sullivan and Langdon carried the day.

Virginia

Governor Edmund Randolph presented the proposed Constitution to the Virginia Assembly in mid-October 1787 and the legislative branch provided for the election of delegates to a state ratifying convention. Virginia delegates—two delegates were selected from each of the 84 counties—debated the merits of the Constitution from June 2 through June 25, 1788 unaware of the speedy New Hampshire ratification. Five delegates changed their mind and accepted the “ratify now, amend later” proposition on June 25. The Recorder, David Robertson, except when he was ill, provided a full account of the proceedings.

Among those delegates who defended the Constitution at the Virginia Ratifying Convention were James Madison, “father of the Constitution;” John Marshall, future Chief Justice of the Supreme Court; and Governor Randolph who nearly a year earlier introduced the Virginia Plan and was one of two Virginia delegates to the Constitutional Convention who refused to sign on September 17, 1787. Opposing adoption of the Constitution were such heavyweights as George Mason, author of the Virginia Bill of Rights and the other non-signer in Philadelphia; Patrick Henry, renowned for his inflammatory, dominating, and passionate speeches; William Grayson, delegate to the Confederation Congress, and James Monroe, future President of the United States and author of the Monroe Doctrine. Summing up the calibre of the delegates, John Marshall said later: “If I were called upon to say who of all men I have known had the greatest power to convince, I should perhaps say Mr. Madison; while Mr. Henry had without doubt the greatest power to persuade.”

The delegates agreed to discuss the Constitution in a “systematic manner.” But the agreement to proceed “clause by clause” was broken early because Henry, starting with the Preamble and Article I, insisted on talking about the “big picture” rather than particular clauses. Delegate Nicholas summarized the early deliberations in this way: “Although we have sat eight days, so little has been done, that we have hardly begun to discuss the question regularly. The rule of the house to proceed clause by clause has been violated.” Henry ignored the requests to address the particular clauses in an orderly manner. On June 15, however, the delegates began a more regular coverage of the Constitution, and engage in a discussion of the powers of Congress in Article I, Section 8. They are particularly concerned about the militia clause and the “sweepings clause” officially known as the necessary and proper clause or the “implied powers” of Congress.

The delegates discussed Article III, the judiciary article, on June 19, 20, 21, and 23. The Convention Recorder, not for the first or last time, notes that Madison said a lot of things “but spoke too low to be understood.” Of considerable interest are Marshall‘s extensive commentary on the jurisdiction of the federal judiciary and Henry‘s personal exchange with George Nicholas over the latter’s comment that Henry has “objected to the whole; and that no part, if he had his way, would be agreed to.” The President of the ratifying convention “hoped gentlemen would not be personal, that they would proceed to investigate the subject calmly, and in a peaceable manner.” On the 23rd and 24th, the delegates discussed Article IV. The issue of ratification then became the focus of attention. Should “previous amendments” be secured before ratification or should ratification occur with the promise to introduce “subsequent amendments?”

The delegates voted 80-88 to reject 20 items in a bill of rights and 20 Amendment proposals as a condition for ratification. The delegates then voted 89-79 to ratify the Constitution with a recommendation that “subsequent amendments” be sent to the First Congress for their consideration. The obvious question is who were the Antifederalists who changed their mind? According to Jackson Turner Main, “some delegates from Kentucky and West Virginia were open to persuasion; arguments of local interest were important in influencing them. The rest probably came from among the following: William Roland, David Patterson, George Parker, and Paul Carrington. W.O. Callis, Cole Digges, Miles King, Burwell Bassett, Willis Riddick, and Solomon Shepherd.”

New York

New York, in many ways, was at the center of the ratification controversy. Robert Yates and John Lansing left the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in early July to launch an attack on the proposed plan. Alexander Hamilton, in turn, launched The Federalist. In October, the New York Journal published the Antifederalist Cato and Brutus essays and The Federal Farmer essays were published in November. According to John Kaminski, “no where else were the people as well informed about the Constitution as in New York.” The newspaper and pamphlet exchanges were extensive during fall 1787. In February 1788, the New York House and Senate narrowly agreed to the calling of a ratifying convention the elections for which took place in late April. The results were made available in late May: 19 Federalists and 46 Antifederalists were going to the ratifying convention. (This is the breakdown offered by Jackson Turner Main.)

Starting June 17, the delegates proceeded to go paragraph by paragraph through the Constitution during the first week of the Convention. Early in the second week—June 24— the delegates received news that New Hampshire, the critical ninth state, had ratified. But the debate continued. Then news that Virginia had ratified reached New York at the end of June. Although the delegates continued their discussion through July 7, there were various moves taking place to seek a compromise solution. Between July 7 and July 14, Antifederalist attempts to secure conditional amendments as well as secession guarantees were defeated. On July 26, New York, by a vote of 30-27—on the promise of recommended amendments—ratified the Constitution and proposed 25 items in a bill of rights and 31 amendments.

In New York, then, the shift is rather huge. From 19 in favor to 46 against, going in, it shifts to 30 in favor to 27 against. There are various possible reasons for this shift. First, is the Massachusetts Compromise and second a strong dose of political realism and statesmanlike prudence. The New York delegates knew that New Hampshire, number nine, and Virginia, number ten, had ratified the Constitution. So Melancton Smith, who was in charge of the Antifederalist opposition, said to the Federalist majority, “I’ll tell you what we’ll do. We’ll favor the Constitution, but we expect you to follow through with your word to do everything you can to accommodate our objections in the First Congress.” Five of the Antifederalists said, “I’m not going with that. I’m going home.” So they left and went home. But most followed Smith‘s lead. Third, there was the threat that if New York failed to ratify, then the southern part of the state would secede.

In New York, as in Virginia and New Hampshire and Massachusetts, the overwhelming majority of Antifederalists turned out in the end to be decent. For all the bluster of Patrick Henry, when they lost in Virginia by that close vote, someone is reputed to have asked Henry, “Well Mr. Henry, what do we do now?” Henry says, “Go home and sleep, and turn up at the next election.” He would obey the outcome and then work within the system. Similarly, given the information that Virginia and New Hampshire had ratified, Melancton Smith, the leader of the Antifederalist opposition in New York, said, “Better to work within the system than outside the system.” He joined fellow delegates Nathaniel Lawrence and Samuel Jones in voting in favor of the Constitution AND tried to work for change within the system. This is important stuff.

Historians tell us that the importance of the 1800 election is that it’s the first peaceful exchange of power from one party to another. Yes, that is extremely important. Here is another thing that’s important. What other country prior to the United States is informed that its government doesn’t work, sits for four months in convention, comes back for an entire year and debates and debates, and not a drop of blood was spilled? A lot of sweat and tears, but no blood. The legacy here from the Federalist–Antifederalist campaign is fight full and free and fair and then be magnanimous in victory and accepting in defeat. The Federalists promised to introduce amendments. But there’s no conditions being made. The Antifederalists decided to become part of the American order.