The Constitutional Convention: Act I, The Alternative Plans

Scene 1: Laying Down the Rules

May 14: Constitutional Convention lacks necessary quorum

Only four delegates from Virginia and four delegates from Pennsylvania present. This Second Monday in May was the day initiated by the Annapolis Convention and confirmed by the Confederation Congress. The delegates “adjourned from day to day until Friday of the said month,” when the quorum requirement was met! The entire Virginia delegation was there within three days of the scheduled start of the Convention. The delegates drafted the Virginia Plan and disseminated it to the arriving delegates over the next week.

May 25: Constitutional Convention meets quorum requirement

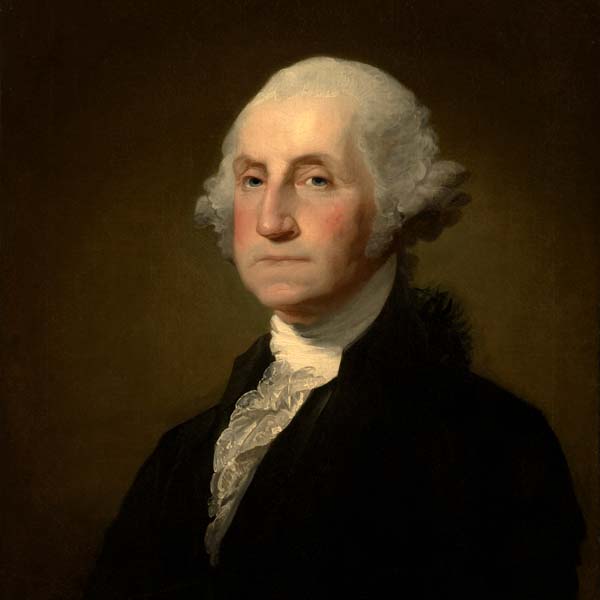

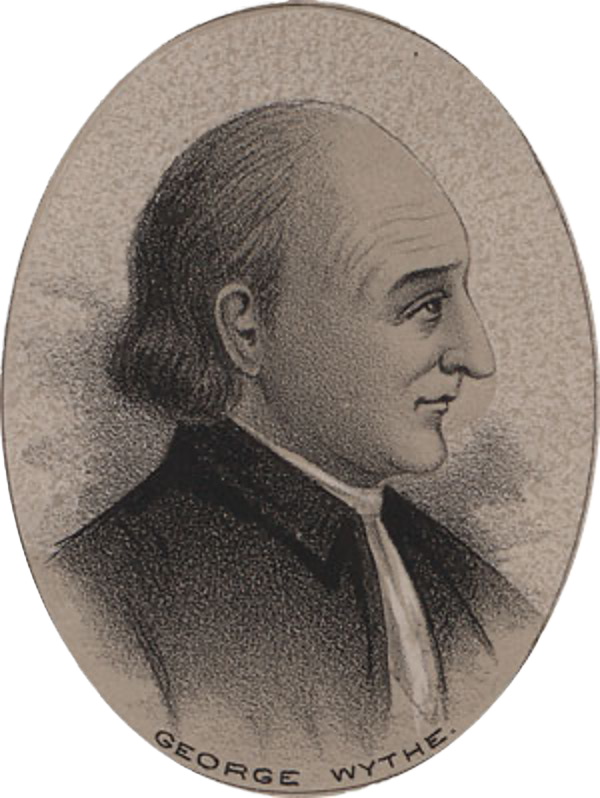

Convened and elected officers: George Washington as President and William Jackson as Secretary. Chose committee (Wythe, Hamilton, and C. Pinckney) to prepare rules.

May 28: Committee on Rules Reports rules for Convention

Adopted sixteen rules and additional suggested rules referred to the committee. The Convention called to reconsider the efficacy of the Articles of Confederation began by adopting five voting rules of the Articles: 1) a quorum required a majority of states, 2) each state was allotted one vote, 3) the voting was to be by states and not by individuals, 4) each state could send up to seven delegates, and 5) each state sets its own internal quorum requirements. (The Convention, also without argument, accepted the “honorary” presence of Franklin as the eighth delegate from Pennsylvania.)

Scene 2: The 15 Resolutions of the Virginia Plan

May 29: Virginia Plan introduced and defended by Randolph

The Committee on Rules reported and five additional rules, including secrecy, were adopted. The language of the secrecy rule was: “nothing spoken in the house be printed, or otherwise published or communicated without leave.” Madison defended the rule in a letter to James Monroe: “it will secure the necessary freedom of discussion.”

Edmund J. Randolph submitted and defended a set of 15 Resolutions, known as the Virginia Plan. Randolph reminded the delegates that their “Mission” was to prevent “the fulfillment of the predictions of the American downfall.” The Convention agreed to meet the next day as a Committee of The Whole to consider the Resolutions.

Charles Pinckney also filed a plan.

Scene 3: First Discussion of the Virginia Plan

May 30: Resolution 1 amended and Resolution 2 discussed

Madison reports that Roger Sherman took his seat. The whole dynamic of the Convention would change as a result of his presence. The Convention resolved itself into Committee of The Whole, Nathaniel Gorham in the Chair. Four votes were recorded with 8 state delegations voting.

Resolution 1

After discussion, agreed (6 – 1 – 1) that a national government consisting of a supreme legislature, judiciary, and executive should be formed. Connecticut voting against, New York divided. G. Morris “explained the distinction between a federal and a national, supreme, Government.” Sherman opposed “too great inroads on the existing system.”

Resolution 2

Discussed whether representation should be based on population or amount of each State’s financial contribution.

May 31: Resolutions 3 – 6 discussed and 5a defeated.

Four votes recorded with ten states voting.

Resolution 3

Decided on a bicameral legislature.

Resolution 4a

Agreed (6 – 2 – 2) on election of First Branch by the people. New Jersey and South Carolina voted “no.” Connecticut and Delaware were divided. New York voted “yes.” Lansing had not yet arrived.

Resolution 5a

Defeated (7 – 3 – 0) Second Branch elected by the First Branch. Only Massachusetts, Virginia, and South Carolina voted in favor of Resolution 5a of the Virginia Plan that called for “the members of the second branch… to be elected by those of the first” based on a scheme of popular representation.

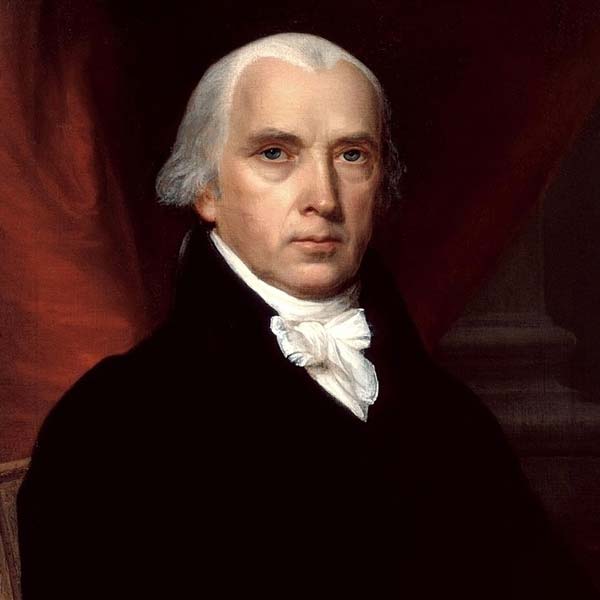

Madison’s reaction: “a chasm (was) left in this part of the plan.”

Roger Sherman’s suggestion to fill the chasm: “election of one member by each of the State Legislatures.”

Resolution 6

Agreed unanimously that either branch could initiate legislation. Agreed unanimously to State Incompetence and Negative on State Laws clauses.

June 1: Debated and postponed Resolution 7 on the Presidency.

Agreed to institute a National Executive with power to carry into effect the national laws and to appoint officers not otherwise provided for. Agreed (5 – 4 – 1) on a seven-year term for Executive. In Massachusetts, King and Gorham vote in favor while Gerry and Strong vote against. Connecticut, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia vote “no.” Postponed consideration of single or plural Executive.

June 2: Further lengthy deliberation of Resolution 7

Confusing day on the Executive. Agreed to selection of Executive by the National Legislature. Agreed on seven-year term (8 – 2), and ineligible after one term (7 – 2 – 1). Dickinson’s motion that Executive be subject to impeachment defeated (9 – 1).

Franklin: Executive should receive no salary. Motion postponed.

June 4: More deliberation of Resolution 7

Seven recorded votes. New Jersey absent.

Resolution 7

Another confusing day on the Executive. Agreed (7 – 3) on single Executive. New York voted “no.” Lansing. and Yates outvoted Hamilton. Virginia voted “yes”: Washington broke a 2-2 tie in Virginia.

Resolution 8

Council of Revision postponed. Agreed (8 – 2) to give Executive a veto over legislation subject to override by 2/3 of each branch of Legislature. Gerry objected to the Judiciary and the Executive having the joint power of prior review: the Judiciary were granted “the exposition of the laws, which involved a power of deciding on the Constitutionality.” King agreed: “the Judges ought to be able to expound the law as it should come before them, free from the bias of having participated in its formation.”

Resolution 9

Agreed to establish a National Judiciary consisting of a Supreme Court and one or more inferior tribunals.

June 5: Consideration of Resolutions 9-15

Resolution 9

Agreed to delete “one or more” and change to “a Supreme Court and inferior tribunals.”

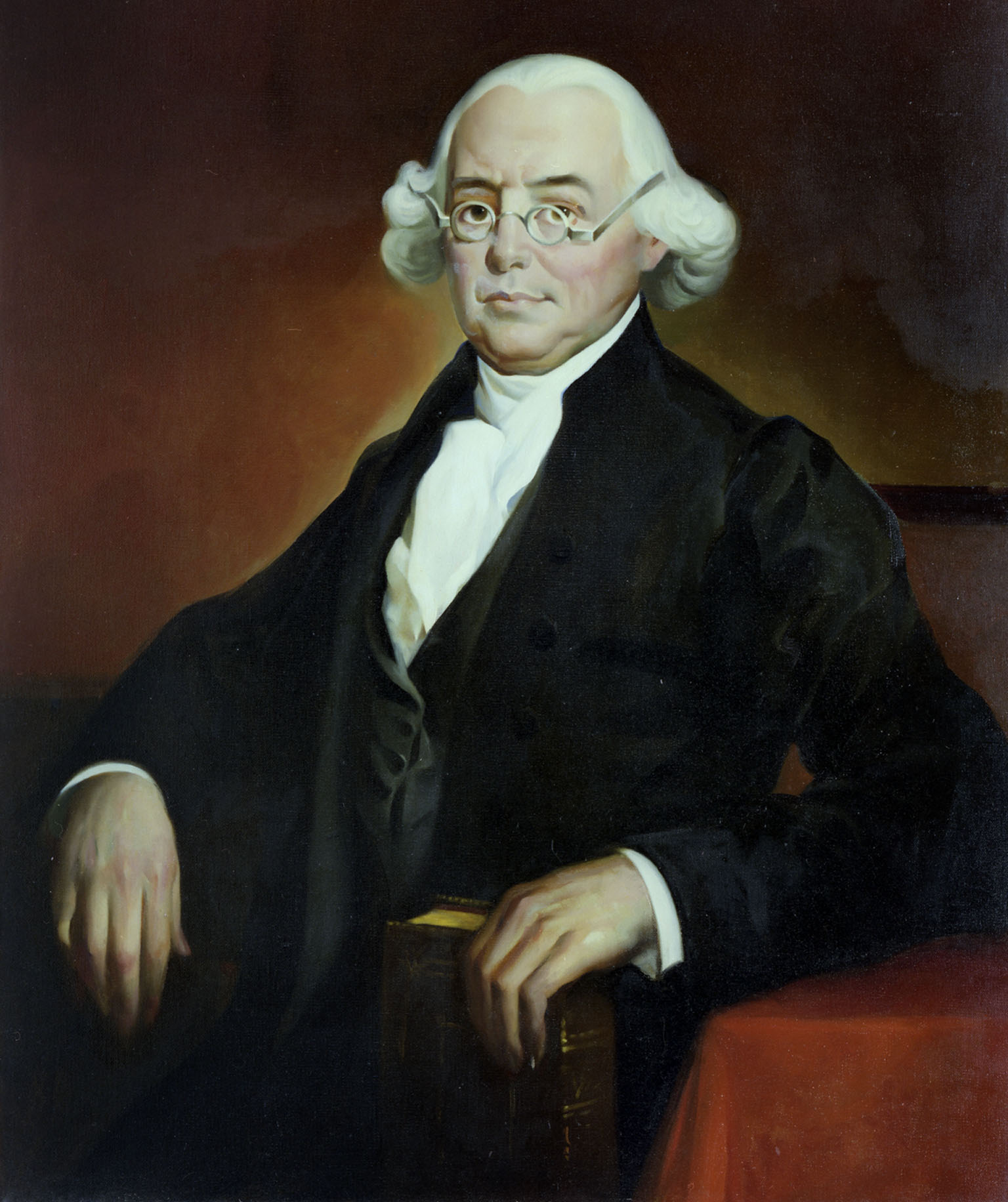

Debated judicial selection and postponed decision, but agreed (8 – 2) to reject approval of judicial appointments by Legislature.

Agreed on judicial tenure during good behavior. Agreed on a salary provision.

Reconsidered inferior tribunals and agreed to eliminate reference to them, then agreed to empower the Legislature to establish such courts.

Resolution 10

Agreed (8 – 2) to admit new states on equal footing with original states.

Resolution 11

Postponed republican guarantee clause until representation is settled.

Resolution 12

Passed an Interim Government provision (8 – 2).

Resolution 13

Postponed provision for Constitutional amendments (7 – 3).

Resolution 14

Postponed oath of officers (6 – 4 – 1). New Jersey voting.

Resolution 15

Postponed mode of ratification of the Constitution. Sherman thought a “popular ratification unnecessary, the Articles of Confederation providing for changes and alterations with the assent of Congress and ratification of State Legislatures.” Madison thought it was “essential” and “indispensable” that “the new Constitution should be ratified in the most unexceptionable form, and by the supreme authority of the people themselves.”

Scene 4: Madison-Sherman Exchange

June 6: Are people ‘more happy in small than large States?’

Resolution 4a

Defeated (8 – 3) motion to have State Legislature elect First Branch of National Legislature. Connecticut, New Jersey, and South Carolina opposed. James Wilson articulated the theoretical issue early in the session: a vigorous general government acquires its “vigorous authority… from the mind or sense of the people at large.” Sherman’s response recalls the argument of the “celebrated” Montesquieu on behalf of the traditional virtues of the small republic and anticipates one of the main Antifederalist themes during the ratification struggle: for republics to be free, they must be small and homogeneous rather than large and heterogeneous. “The objects of the Union, he thought were few… All other matters civil and criminal would be much better in the hands of the States. The people are more happy in small than in large States.” Besides, it is not the factious nature of the people that must be guarded against; rather it is the corruption of the politicians who are unable to resist the temptation of political power. Madison’s argument in favor of popular representation focused on 1) the dangers of majority faction, especially concerning the property question, and 2) the solution residing in the control of the effects of faction rather than in the elimination of the causes of faction. This June 6 speech points us back to his Vices, written in Spring 1787, and forward to Federalist 10. The extended republic argument of the Vices and Federalist 10 are intertwined with 4a of the Virginia Plan. And the link is what is to be done about controlling the effects, in contrast to eliminating the causes, of majority faction. Madison claimed that to “enlarge the sphere… was the only defense against the inconveniences of democracy” in “civilized societies”—those attached to the preservation of the diversity of opinions, passions, and interests in a free society—consistent with “the democratic form of Government.” Faction, in effect, is sown in the nature of man and when we have democratic or republican government, we get a factious majority tyrannizing an unprotected minority: “We have seen the mere distinction of color made in the most enlightened period of time, a ground of the most oppressive dominion ever exercised by man over man… Debtors have defrauded their creditors. The landed interest has borne hard on the mercantile interest.” Madison wanted a modification in the structure of the Articles of Confederation because they preserved the privileged position of the State Legislatures who were guilty of putting the revolutionary principles of economic liberty, political liberty, and religious liberty in danger.

Resolution 8a Reconsidered

The second vote of the day concerned the Council of Revision provision of the Virginia Plan. The Council of Revision added “a convenient number of the national Judiciary to the Executive in the exercise of the negative” over acts of Congress. The vote was 8-3 against the proposition. Only Connecticut, New York, and Virginia voted in favor of the Council of Revision.

Scene 5: Second Discussion of the Virginia Plan

June 7: How to fill ‘the chasm’ created by defeat of Resolution 5a

Resolution 5a

Agreed (11 – 0) to election of Second Branch of National Legislature by State Legislatures. This proposal by Dickinson and Sherman filled the “chasm” mentioned by Madison. He argued that the purpose of the Senate is to proceed “with more coolness, with more system, and with more wisdom, than the popular branch.” Madison failed to carry Virginia.

June 8: Resolution 6 and the Negative on State laws

Resolution 6

A move by Madison and Pinckney to extend the Congressional negative to all state laws was defeated (7 – 3 – 1). Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, and Virginia were in favor with Delaware divided. Pinckney failed to carry South Carolina. Virginia’s vote was 3 – 2. According to Madison, “Mr. Randolph and Mr. Mason no. Mr. Blair, Doctor McClurg, Mr. Madison yes. General Washington not consulted.”

June 9: Reconsideration of Resolution 7

Resolution 7

Defeated (10 – 1) a motion by Gerry that State Executives elect the National Executive. Delaware divided.

Resolution 4a

Debated voting procedures within the National Legislature.

Scene 6: The 19 Resolutions of the Amended Virginia Plan

June 11: Popular representation in both branches?

G. Morris absent today until June 30.

Resolution 4a

Return to National Representation. Sherman proposes a compromise: popular representation in the House and equal State representation in the Senate. South Carolina suggests that wealth, and not just people and States, be represented. According to Butler, “money was power.” Wilson introduces the 3/5 Clause. Decided (9 – 2) that representation in First Branch of the National Legislature should be based on free population plus 3/5 of all other persons. Only New Jersey and Delaware vote “no.” Sherman and Ellsworth now propose one vote per state in the Senate. Sherman: “Everything depended on this. The smaller States would never agree to the plan on any other principle than an equality of suffrage in this branch.” Disagreed (6 – 5) that each State should be equally represented in Senate. Wilson assisted Madison in defeating Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Delaware, and Maryland.

Resolution 5a

Agreed (6 – 5) that representation in the Second Branch should also be proportional plus 3/5 of all other persons. Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Delaware, and Maryland vote “no.” The June 11 version of the “Connecticut Compromise” failed.

Resolution 13

Discussed.

Resolution 14

Agreed (6 – 5) to require oaths to observe the National Constitution and National laws by State officers. Sherman “opposed it as unnecessarily intruding into the State jurisdictions.”

June 12: The Specifics of Representation

Resolution 15

Agreed (5 – 3 – 2) to refer the Constitution to the people of the several states for ratification. Pennsylvania not voting. Delaware and Maryland divided. Connecticut, New York, and New Jersey voted “no.”

Resolution 4b

Agreed (7 – 4) on three-year terms for First Branch of National Legislature. Massachusetts, Connecticut, North Carolina, and South Carolina voted “no.”

Resolution 4c

Struck out, without discussion, rotation and recall provisions, thus marking the end of the “small republican” legislative tradition.

Resolution 4d

Agreed (8 – 3) to provide “liberal compensation” for members of the First Branch “to be paid from the National Treasury.”

Resolution 4e

Agreed (8 – 1 – 2) to make members of First Branch ineligible for offices under the National Government for one year after leaving the House. Maryland divided.

Resolution 5b, c

Agreed to require a minimum age of 30 (7 – 4) and a seven-year term for Senators (8 – 1 – 2). Georgia and North Carolina divided.

Resolution 5d

Defeated (7 – 3 – 1) no pay for Senators. Maryland divided.

Resolution 9

Discussed and postponed the jurisdiction to be given the Supreme Court.

June 13: The 19 Resolutions of the Amended Virginia Plan continued

Resolution 9

Agreed that the jurisdiction of the National Judiciary should extend to cases concerning the collection of the national revenue, impeachment of any national officers and questions of national peace and harmony.

Agreed that the Supreme Court should be appointed by the Senate.

Resolution 6

Rejected (8 – 3) a motion requiring money bills to originate only in the First Branch of the Legislature.

Received and agreed to vote on Amended Virginia Plan with 19 resolutions.

Scene 7: The 9 Resolutions of the New Jersey Plan Discussed

June 14: Dickinson to Madison: “you see the consequences of pushing things too far.”

New Jersey requested postponement of Amended Virginia Plan to present an alternative plan. Paterson wanted to introduce a plan that was “purely federal.” A postponement was agreed to.

June 15: New Jersey Plan introduced

Paterson submitted 9 Resolutions. The Plan restored the single chamber of the Articles of Confederation with each State represented equally regardless of population size. The power to tax and regulate interstate commerce was added. The other key features of the New Jersey Plan were: 1) the absence of popular representation, 2) a unicameral legislature, 3) equal representation of the States, and 4) the States retained as the central structural players. New Jersey actually met their own internal quorum requirements on this day!

June 16: The New Jersey Plan is “legal” and “practical”

The New Jersey Plan was debated. The Plan increases the powers of Congress, but leaves the federal structure of the Articles of Confederation unaltered. Paterson: “Our object is not such a Government as may be best in itself, but such a one as our Constituents have authorized us to prepare, and as they will approve.” Wilson “conceived himself authorized to conclude nothing, but to be at liberty to propose anything.” Pinckney remarked that there was no principle involved: “Give New Jersey an equal vote,” and she “will dismiss her scruples.” Randolph: “When the salvation of the Republic was at stake, it would be treason to our trust, not to propose what we found necessary.”

Scene 8: The 11 Resolutions of Hamilton’s Plan Presented

June 18: Neither the Virginia Plan nor the New Jersey Plan is adequate to secure “good government”

Hamilton argues that the Virginia Plan does not go far enough in enhancing the powers or altering the existing structure of the federal arrangement to secure “good government.” According to Hamilton, “we ought to go as far in order to attain stability and permanency, as republican principles will admit.” He recommends 11 ways to create a strong central and republican government. This is the first time that the word “vested” has been used to identify the location of political power. Note Hamilton’s Hamilton’s position on war powers.

Scene 9: Decision Day – Adoption of the Amended Virginia Plan

June 19: New Jersey Plan rejected

Defeated (6 – 4 – 1) Dickinson’s motion to defer consideration of the New Jersey Plan. Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, and Delaware voted “no.” Maryland divided. Heard Madison’s eight arguments against the New Jersey Plan. “The great difficulty lies in the affair of Representation; and if this could be adjusted, all others would be surmountable.”

Defeated the New Jersey Plan (7 – 3 – 1). Connecticut voted “yes!” New York, New Jersey, and Delaware voted “no.” Maryland divided.

Madison summarized Act I. The issue was “the great difficulty” of representation. The coalition in favor of equal representation for the States “began now to produce serious anxiety for the result of the Convention.”