The Constitutional Convention: Act III, The Committee of Detail Report

Scene 1: The Structure and Powers of Congress

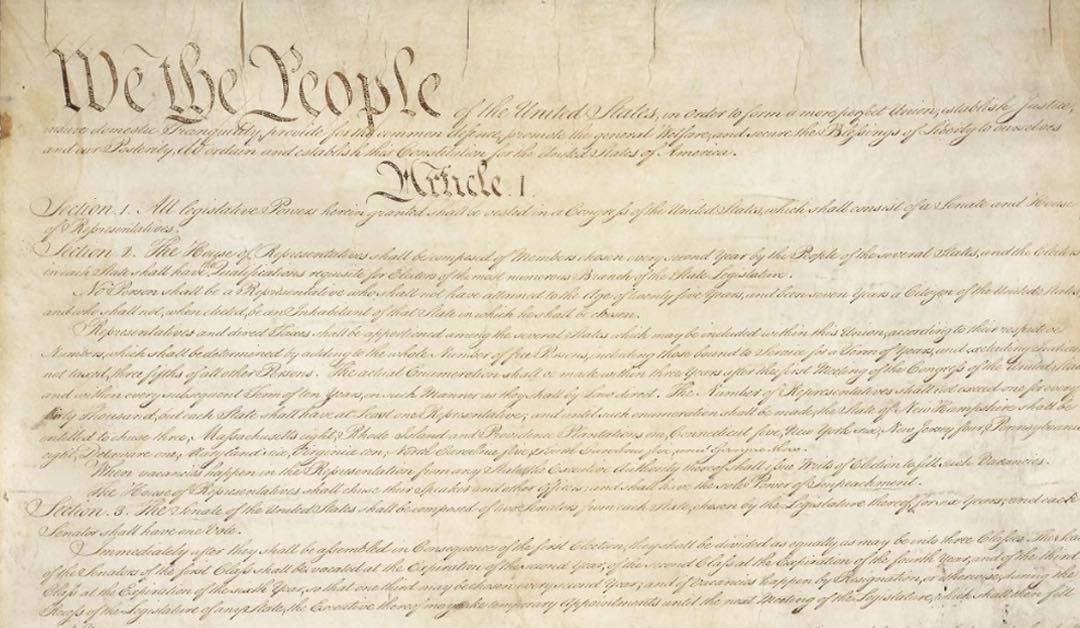

August 6: Twenty-Three Articles presented

The Convention received the Report of the Committee of Detail and adjourned to read the 23 Articles. Eight States present. Mercer from Maryland took his seat.

August 7: Articles I-IV and the suffrage issue

Ten States present. Began consideration of the Committee of Detail Report in a Committee of the Whole and covered the Preamble, Articles I, II, III, and part of Article IV.

Agreed (10 – 0) to Preamble and Articles I and II.

Took up Article III (two-branch legislature). Agreed (7 – 3) to delete reference to mutual veto between Houses of Congress. Discussed Congress meeting 1st Monday of December annually, and agreed to add, “unless a different day shall be appointed by law” (8 – 2). Motion for May meeting instead of December defeated (8 – 2). Agreed to Article III as amended. Took up Article IV, Section 1 (House elections). Ellsworth and Mason object to the attempt by G. Morris and Dickinson to impose electoral restrictions. Defeated more restrictive freehold qualifications on the electors (7 – 1 – 1).

August 8: Article IV deliberated

Agreed unanimously to Article IV, Section 1 concerning qualifications of the electors: “the qualifications of the electors shall be the same as those of the electors in the several States of the most numerous branch of their own legislature.”

Proceeded to Article IV, Section 2 (qualifications of House members). Agreed (10 – 1) to seven instead of three years citizenship. Agreed to substitute “inhabitant” instead of “resident”; defeated motions to require 3 years (9 – 2) and 1 year (6 – 4 – 1) of residence, and approved the section (11 – 0).

Agreed to Article IV, Section 3: 65 members in House from First Congress until the first census.

Took up Article IV, Section 4 (future apportionment of House). Agreed (9 – 2) to insert “not exceeding” before 40,000. Considered last clause of Section 4: “The Legislature shall… regulate the number of representatives by the number of inhabitants… at the rate of one for every forty thousand.” Defeated (10 – 1) a motion by G. Morris to insert “free” before inhabitants. G. Morris: “Slavery was a nefarious institution.” Agreed to add a provision introduced by Dickinson for at least one representative for each state in the House.

Moved on to Article IV, Section 5 (money bills). Approved motion to strike (7 – 4), thus challenging the Connecticut Compromise. Pinckney, G. Morris and Madison carry the day on this motion. Mason: “to strike out the section, was to unhinge the compromise of which it made a part.”

August 9: Article V dissected

Took up Article IV, Section 6 (sole power of impeachment, choose its own speaker) and 7 (filling vacancies) and approved both.

Considered Article V, Section 1 (selection of Senators and provision for vacancies).

Defeated motion to strike executive appointment to supply vacancies (8 – 1 – 1). Agreed to give each Senator one vote and each State two members.

Article V, Section 2 agreed, nem con.

Article V, Section 3 (qualifications): 30 years old, citizen for 4 years, resident.

Defeated motion to require 14 years of citizenship (7 – 4), and 13 years of citizenship (7 – 4).

Defeated motion to require 10 years, (7 – 4), agreed to 9 years (6 – 4 – 1).

Substituted “inhabitant” for “resident”.

Article V, Section 4 (Senate shall choose own officers) approved.

Took up Article VI, Section 1 (times and places of election) amended and approved.

Randolph objects to defeat of Article IV, Section 5 (Money Bills).

August 10: Article VI and Pinckney’s property qualifications

There were nine recorded votes. Eleven States voted except Delaware was absent for the first two votes. New Hampshire was divided on the final vote. Pennsylvania divided on the fifth vote.

Reheard Article IV, Section 2 (giving Legislature authority to establish property qualification for members). Motion by Pinckney to spell out property qualifications in the Constitution rejected on voice vote. Pinckney suggested $100,000 for President and $25,000 for representatives. “The motion of Mr. Pinckney was rejected by so general a no, that the States were not called.” Reconsidered (6 – 5) House residence requirement in Article IV, Section 2, and substituted three years for seven at request of Wilson.

Took up Article VI, Section 3 (Quorum requirements). Added power to compel attendance of absent members (10 – 0 – 1).

Agreed to Article VI, Section 4 (each House to judge qualifications and elections of its members).

Article VI, Section 5 (freedom of debate), passed nem con.

Took up Article VI, Section 6 (rules, punishment for disorderly behavior, expulsion of members). Agreed (10 – 0 – 1) to require 2/3 vote for expulsion.

Took up Article VI, Section 7 (Requiring journal and a record of each vote at request of 1/5 of members present), passed (7 – 3 – 1).

August 11: Article VI continued

There were eight recorded votes. Eleven States voted. South Carolina divided on the final vote.

Continued on Article VI, Section 7. Agreed (6 – 4 – 1) to non-publication in the journal of “such parts as may in their judgment require secrecy.”

Took up Article VI, Section 8 (no more than 3-day adjournment without consent of other House nor to a location other than where they are sitting). Amended (10 – 1) to preclude adjournment to another place during a session.

Reconsidered Article V, Section 5 (money bills to originate in House, and not be subject to Senate amendment).

Agreed (8 – 2 – 1) to reconsider the money bills provision on Monday.

August 13: Reconsideration day and Dickinson’s remark: “Experience must be our only guide. Reason may mislead us.”

There were ten recorded votes. Eleven States voted. Pennsylvania divided on the fifth vote. Hamilton makes a rare appearance. He left the Convention on June 30. After today, he is gone again until September 6. New York has lacked a quorum since July 10. Hamilton spoke but New York could not vote.

Reconsidered Article IV, Section 2 (House age and citizenship). Defeated (7 – 4) Hamilton’s motion to eliminate seven-year citizenship requirement. Butler opposed this effort to “increase” the influence of “foreigners into our public councils.” Connecticut, Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia voted to support Hamilton’s motion. Defeated nine-year citizen requirement (8-3), and defeated five-year citizen requirement (7-3-1). Pennsylvania divided. Agreed to the section as reported.

Reconsidered Article V, Section 3 (age and citizenship for Senators), and defeated a motion (8 – 3) to reduce 9 years to 7.

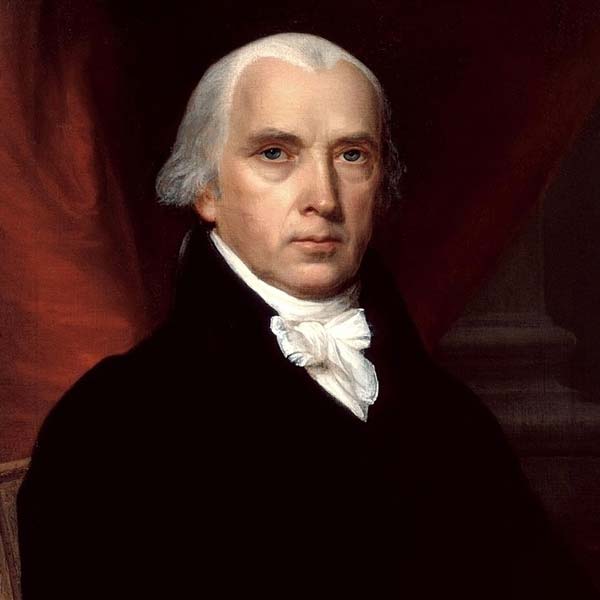

Reconsidered Article IV, Section 5 (money bills). Randolph moved to reinstate exclusive power over money bills to the House. Mason and Randolph argued that a revolutionary principle was at stake. Madison and Blair, also from Virginia, saw no principle at stake. Dickinson urged that “experience” be the guide. Washington supported Randolph and Mason on prudential grounds. Defeated (7-4) the motion to reinstate original agreement on money bills. Virginia voted “yes.” Delegates voted (8-3) that the Committee on Detail report on money bills be accepted. Virginia voted “no.”

August 14: Article VI and ineligibility

There were three recorded votes. Eleven States voted.

Took up Article VI, Section 9 (ineligibility of members of legislature to other Federal Offices). Vote was 5-5-1. Georgia was divided on this first vote. Postponed until powers of Senate were determined.

Amended Article VI, Section 10 (legislative pay ). Voted 9-2 that the National Treasury rather than State Legislatures should pay the representatives. Massachusetts and South Carolina voted “no.” Agreed that pay be ascertained by law.

August 15: Reintroduction of Council of Revision

There were six recorded votes. Eleven States voting.

Approved Article VI, Section 11 (enacting style for bills).

Took up Article VI, Section 12 (either House may originate bills). Postponed (6 – 5) pending determination of powers to be given Senate.

Took up Article VI, Section 13 (Presidential veto). (See coverage on June 4, June 6, and July 21.) (See also coverage on June 4, June 6, and July 21.) Defeated (8 – 3) a motion that all bills should be submitted to the Executive and Judiciary before (Council of Revision) they become law. Only Delaware, Maryland, and Virginia in favor of the Council of Revision. Thus Madison's provision for the Committee of Revision was defeated for the fourth and final time.

Agreed (6 – 4 – 1) to 3/4 vote to override Presidential Veto. Pensylvania divided. Agreed (9 – 2) to 10 days instead of 7 for the President to return bills. New Hampshire and Massachusetts “no.”

August 16: Deliberation of the Enumeration of Congressional powers

There were four recorded votes. Eleven states voted.

Took up Article VII, Section 1 (enumeration of Congressional powers). The Committee of Detail tried to forge a middle ground between the open-ended grant of powers under the various versions of the Virginia Plan and the very specific listing of powers under the Articles of Confederation and the New Jersey Plan. Thus they recommended an “enumeration of powers” as well as a “necessary and proper” clause. Hamilton was absent.

Agreed, nem con, to power to lay and collect taxes, regulate international and interstate commerce, coin money, regulate foreign coin, and fix standards of weights and measures. Approved (6 – 5) adding “and post roads” to the power to “establish Post offices.” Pennsylvania “no,” and Virginia “yes.” Agreed (9 – 2) to strike out the words “and emit bills” in the 8th clause of Article VII, Section 1. New Jersey and Maryland “no.”

August 17: Deliberation of the Enumeration of Congressional powers

There were 10 recorded votes. Delaware was absent on the first vote, but present for the rest. New Jersey was present for the first vote but absent for the rest.

Resumed discussion of Article VII, Section 1 (enumeration of Congressional powers).

Agreed (7 – 3) to elect Treasurer by joint ballot (Delaware not voting). Agreed to “establish inferior courts, and make rules on captures.” Agreed (7 – 3) to “define and punish piracies and felonies committed on the high seas.” Virginia votes “no.” Agreed similarly to “counterfeiting the securities and current coin of the United States, and offenses against the law of nations.”

Changed (7 – 2) the clause Congress shall “make” war to Congress shall “declare war.” New Jersey and Massachusetts absent. Hamilton was also absent.

The Framers apparently 1) wanted to avoid the idea that it is legitimate for a democratic republic, expressing its opinion through the Congress, to initiate, or MAKE, war but at the same time recognize the legitimate need for a democratic republic, through the executive branch, to defend itself from sudden invasion; 2) believed that “declare war” is more compatible than “make war” with the idea of a just war; and 3) they did not want Congress to be in the business of the day-to-day operations of making war in the sense of carrying out the specifics of military policy. Thus 4) we must ask the question where did MAKE WAR go when the Framers substituted DECLARE WAR? Did MAKE disappear or become CONDUCT or did MAKE go somewhere else?

“Separate questions having been taken on the 9, 10, 11, 12, and 14 clauses of the 1st Section, 7 article as amended. They passed in the affirmative.”

August 18: Creation of Committee of 11

Referred a list of suggested additional Congressional powers to the Committee of Detail.

Agreed (6 – 4 – 1) to a Committee of 1 per state, chaired by William Livingston, to consider assumption of state debts. Pennsylvania divided. Clymer chosen from Pennsylvania.

Agreed (9 – 2) to meet daily, except Sunday, from 10:00 till 4:00, with no earlier adjournment allowed. Pennsylvania and Maryland voted “no.”

Continued discussion of Article VII, Section 1 (enumeration of Congressional powers). Agreed to add “and support” to the power to raise armies and agreed to strike “build and equip” in favor of “provide and maintain” navy. Agreed to add power to make rules for government and regulation of land and naval forces. Considered different motions giving authority over militia and referred them (8 – 2 – 1) to a committee. Connecticut and New Jersey voted “no.” Maryland divided.

August 20: Article VII and the Issue of a Bill of Rights

There were 11 votes recorded. Eleven states present. Williamson of North Carolina wrote to Governor Caldwell that Davie left on August 13 and that Alexander Martin would leave on August 27. North Carolina was divided on the third and tenth votes.

Pinckney introduced a list of 12 rights. Included are references to liberty of the press, the writ of Habeus Corpus, and that “no religious test or qualification shall ever be annexed to any oath of office under the authority of the U. S.” They are sent to the Committee of Detail.

G. Morris proposes the foundations for a Presidential Cabinet: Council of State, Domestic Affairs, Commerce and Finance, Foreign Affairs, War, and Marine. These are referred to the Committee of Detail.

Returned to Article VII, Section 1 (enumeration of Congressional powers). Necessary and Proper Clause passed. Defeated (8 – 3) Mason’s proposal to give Congress power to enact sumptuary laws. Mason did not carry Virginia.

Took up Article VII, Section 2 (defining treason). After debate and numerous amendments, Section 2 was approved.

Took up Article VII, Section 3 (direct tax, House apportionment and census). Agreed (9 – 2) to have first census within 3 years. South Carolina and Georgia “no.”

Scene 2: The Slavery Question and the Creation of the Judiciary

August 21: Report of the Committee of 11

There were seven recorded votes. Eleven States present.

Heard a report from the Committee of State Debt Assumption and Militia Regulation, and laid it on the table.

Included in the Committee of 11 Report was the clarification that debts would be incurred only “for the common defense and general welfare.” This was the first appearance of these two clauses.

Resumed discussion of Article VII, Section 3, and agreed to it (10 – 1). Delaware voted “no.”

Continued discussion of Article VI, Section 12 (origination of bills): Defeated (8 – 2 – 1) motion to apportion direct taxes to the number of representatives pending the first census. North Carolina divided.

Took up Article VII, Section 4 (no export taxes by States). Defeated (7 – 3) move to allow export taxes for revenue only. Defeated (6 – 5) motion to permit export taxes with 2/3 majority vote. Approved Section (7 – 4).

Took up Article VII, Section 4, Clauses 2 and 3 (no interference with the slave trade). Congress cannot tax or prohibit “the migration or importation of such persons as the several States shall think proper to admit.”

L. Martin, supported by Mason, suggests that the slave trade be prohibited or at least taxed. He argued that the importation of slaves “was inconsistent with the principles of the revolution.” Rutledge rejoined, “Interest alone is the sovereign principle with Nations.” Ellsworth: “The morality or wisdom of slavery are considerations belonging to the States themselves.”

Three clearly identifiable positions have emerged on the issue of the slave trade: 1) the slave trade violates American principles. Thus ban, or at least discourage, the slave trade because it “was inconsistent with the principles of the revolution and dishonorable to the American character.” This was the position articulated by Luther Martin of Maryland on this day and supported by the Virginia delegation as well as delegates from New Hampshire, Delaware, and Pennsylvania. 2) Rutledge best represented the second position. This position was supported by the other delegates from South Carolina, North Carolina, and Georgia delegations: “Religion and humanity had nothing to do with this question — Interests alone is the governing principle with Nations — The true question at present is whether the Southern States shall or shall not be parties to the Union.” 3) The third position was that occupied by Connecticut. Mr. Ellsworth summed up the issue thus: He was in favor of ” leaving the clauses as it stands. Let every State import what it pleases.”

August 22: Article VII, Section 4: Slavery

Resumed discussion of Article VII, Section 4.

C. Pinckney stated, “if slavery be wrong, it is justified by the example of all the world.” Rutledge warns that North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia will not sign the Constitution without certain slavery protection clauses. Dickinson considered the importation of slaves “as inadmissible on every principle of honor and safety. “Randolph added that he “could never agree to the clause as it stands” and urged that the entire section be referred to a committee to seek a compromise solution. Sherman: “it was better to let the Southern States import slaves than to part with them, if they made that a sine qua non.” Baldwin assured his colleagues that if Georgia were left to herself, “she may probably put an end to the evil.” King thought the whole subject “should be considered in a political light only.”

Voted (7 – 3 – 1) to commit Article VII, Sections 4 and 5 to an 11-member committee chaired by Livingston. The members of the committee: Langdon, King, Johnson, Livingston, Clymer, Dickinson, L. Martin, Madison, Williamson, C. C. Pinckney, and Baldwin. North Carolina was divided on submitting to a committee. Connecticut, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania voted not to commit. C. Pinckney and Rutledge were not selected. Dickinson, L. Martin, and Madison have each expressed their strong opposition to the slave trade. It is important to note that the delegates were determined to revisit the slavery provisions of the Committee of Detail Report and seek an alternative position.

Voted (9 – 2) to commit Section 6 to the same committee.

Took up Article VII, Section 2 (prohibit bills of attainder and ex-post facto laws). Agreed (7 – 3 – 1). North Carolina divided.

The report of the Committee of 5 was postponed (6 – 5).

The report of the Committee of 11 on Assumption of State Debts was taken up. After brief discussion it was agreed (11 – 0), “The Legislature shall discharge the debts and fulfill the obligations of the United States.”

August 23: Discussion of Articles VII-IX

There were eight recorded cotes. Eleven states present and voted on the first six votes. Ten states voting on the last two votes. New Hampshire absent for these two votes. North Carolina divided on the last vote.

Took up Article VII, Section I (powers of Congress). After considerable discussion and minor alterations agreed to Section 1. The Necessary and Proper Clause generated little debate.

Passed Article VII, Section 7 (no titles of nobility) nem con.

Took up Article VIII. Approved adding a prohibition against Federal officers accepting foreign titles or gifts without consent of Congress. Also accepted a restatement of Supremacy Clause.

Took up Article IX (Senate treaty power and appointment of Judges and ambassadors), and postponed.

Took up Article VII, Section 1 (calling up militia to execute laws), amended and approved it.

Madison again, supported by Reheard Article IV, Section 2 (giving Legislature authority to establish property qualification for members). Motion by Pinckney to spell out property qualifications in the Constitution rejected on voice vote. Pinckney suggested $100,000 for President and $25,000 for representatives. “The motion of Mr. Pinckney was rejected by so general a no, that the States were not called.” Reconsidered (6 – 5) House residence requirement in Article IV, Section 2, and substituted three years for seven at request of Wilson and C. Pinckney, proposed a motion to restore Congressional veto power over State laws. Wilson thought, “this is a key-stone wanted to complete the wide arch of Government we are raising.” Sherman and Williamson “thought it unnecessary.” The motion was defeated (6 – 5).

Agreed to revised Article VII, Section 1 (debts). “The Legislature shall fulfill the engagements and discharge the debts of the United States, and shall have the power to lay and collect taxes, duties, imposts, and excises.”

Resumed discussion of Senate power to make treaties, appoint Ambassadors and Judges, and referred proposal to the Committee of Five.

August 24: Committee of 11 reports on slavery

There were 13 recorded votes. North Carolina absent on the first vote; Pennsylvania absent on the first three votes. Eleven States voted on the fourth through the ninth votes. Ten States voted on the last four votes. North Carolina absent for the last three votes and Massachusetts absent for the tenth vote. Connecticut divided on the ninth and tenth vote. Maryland divided on the ninth vote.

Heard a report from the Livingston Committee on Slave Trade Article VII, Sections 4, 5, and 6 (no interference with slave trade, capitation taxes in proportion to census, no navigation acts without 2/3 vote in each House). Committee recommended prohibiting Congressional interference with the slave trade until 1800, keeping Section 5, striking section 6 and permitting a tax to be imposed on migration and importation.

Agreed to reconsider debt provisions and interstate commerce clause (Article VII, Section 1).

Took up Article IX, Sections 2 and 3 (controversies among states, controversies arising from conflicting land grants). Voted (8 – 2) to strike out both sections.

Took up Article X, Section 1 (Executive). Agreed on one Executive but defeated four different methods of electing the President including direct election by the people (9 – 2) and by electors (6 -5).

Took up Article X, Section 2 (Executive powers and duties).

Ordered adjournment at 3 o’clock for the future.

August 25: The Slavery Question (see also July 23, August 8, 21, 22, 26, and 29)

There were nine recorded votes. Eleven States present for the first four votes. New Jersey absent for votes 5-9. Maryland was divided on the fifth vote.

Approved (10 – 1) debt provision. Defeated (10 – 1) motion to include common defense and general welfare clause in Article VII, Section 1.

Took up Article VII, Section 4 (slave trade). C. C. Pinckney who was a member of the Livingston Committee, “moved to strike out the words ‘the year eighteen hundred’ and insert 1808 instead.” Agreed (7 – 4) to change from 1800 recommendation of the Livingston Committee to 1808 concerning the prohibition on Congress with respect to the international slave trade. (New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, and Virginia voting against. They wanted 1800.) Madison stated, “twenty years will produce all the mischief that can be apprehended from the liberty to import slaves.” He also “thought it wrong to admit into the Constitution the idea that there could be property in men.” G. Morris wanted the clause to say this was a compliance with “North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia.” Dickinson urged that the clause be confined to those states “now existing.” Agreed nem. con. Also approved a slave trade import tax not to exceed $10.00 per person.

Approved, nem. con., Article VII, Section 5 as reported.

Postponed Article VII, Section 6.

Article X, Section 2. Defeated (6 – 3 – 1) motion allowing appointment to Federal offices by State Executives.

August 27: Articles X and XI discussed

There were eleven recorded votes on this day. Eight states were present for votes 1-5 and votes 8-11. Seven states – the minimum for a Convention quorum – were present for votes 6-7. Massachusetts, New Jersey, and North Carolina missed votes 1-11 because these states failed to meet their own internal quorum requirement for the entire day. Georgia was absent for votes 6-7. Maryland was evenly divided on vote 6. What is interesting is the extensive non-attendance.

Continued on Executive powers in Article X.

Agreed (6 – 2) that President would be “commander-in-chief of the militia when called into the actual service of the United States.” Massachusetts, New Jersey and North Carolina absent. Delaware and South Carolina “no.”

Took up Article XI, Section 1: “The Judicial Power of the United States…” Agreed to Johnson’s motion to add “both in law and equity” after the words “United States.” Approved Section 1 (6 – 2)

Took up Article XI, Section 2. Defeated (7 – 1) removal of justices by Executive on request of Legislature. Connecticut disagreed.

Began discussion of Article XI (judicial powers).

Took up Section 1: “The Judicial Power of the United States…” Agreed (6-2) to Johnson’s motion to add “both in law and equity” after the words “United States.” Three states absent. Approved Section 1 (6-2).

Took up Section 2: Defeated (7-1) removal of justices by Executive on request of Legislature. Approved Section 2 (6-2).

Took up Article XI, Section 3. Postponed clause considering the impeachment of Judges. Discussed distinction between original and appellate jurisdiction. Agreed to add, “to which the United States is a Party” to “controversies.” Approved (8 – 2) several other perfecting amendments. Johnson moved to insert the words “this Constitution and the” before the word “laws” in “The jurisdiction of the Supreme Court shall extend to all cases arising under the laws passed by the Legislature of the United States.” This passed nem. con. on the understanding that the jurisdiction was “limited to cases of a Judiciary nature.”

Massachusetts, New Jersey, and North Carolina experienced difficulties meeting quorum requirements.

Johnson of Connecticut moved that the power of the Judiciary shall extend to all cases “both in law and equity” arising under “this Constitution.” Madison was concerned: did this give the Judiciary an unrestrained reach into all cases involving law and equity. Johnson assured the delegates that he meant, “that the jurisdiction given was constructively limited to cases of a Judiciary nature.” Johnson did not intend his motion to be an invitation to the Judiciary to open up the Constitution and make decisions of a political nature. With this assurance, the motion was agreed to nem. con.

Approved Article XI, Section 2 (6-2). Delaware and Maryland “no.”

Took up Article XI, Section 3. Postponed clause considering the impeachment of judges. Discussed distinction between original and appellate jurisdiction. Agreed to add, “to which the United States is a Party” to “controversies.”

Approved (8-2) several other perfecting amendments.

Massachusetts, New Jersey, and North Carolina experienced difficulties meeting quorum requirements.

August 28: Articles XI-XV discussed

Heard a report from August 25th committee (regulation of commerce).

Continued discussion of Article XI.

Took up Section 3 (appellate jurisdiction). Approved Section 3 (9 – 1).

Took up Section 4 (local trial by jury and Writ of Habeas Corpus). Amended to provide for crimes committed outside any state. Agreed (7 – 3) to add that the privilege of the writ of Habeas Corpus shall not be suspended, unless where in cases of Rebellion or invasion the public safety may require it. Agreed to Section 4.

Agreed to Section 5 (limit punishment under impeachment).

Took up Article XII (limits on State powers). Agreed (8 – 1 – 1) to add prohibition on emitting bills of credit, or making anything but gold or silver legal tender. Maryland voting against. Agreed (7 – 3) that no State could pass bills of attainder or ex post facto laws. Defeated (8 – 3) prohibiting laying of embargoes. Agreed to Article XII as amended.

Took up Article XIII (additional prohibition on States). Agreed (6 – 5) to prohibit States from taxing exports as well as imports without consent of Congress. Agreed (9 – 2) that net receipts of State taxation of imports and exports go into Federal Treasury. Agreed to Article XIII.

Took up Article XIV (mutual privileges and immunities). Approved it (9 – 1 – 1).

Took up Article XV (extradition): “Any person charged with treason, felony or high misdemeanor in any State, who shall flee from justice, and shall be found in any other State, shall, on demand of the Executing power of the State from which he fled, be delivered up and renewed to the State having jurisdiction of the offence.” Soon after, “high misdemeanor” replaced by “other crime.” Agreed to Article XV, nem con.

There were 12 recorded votes on this day. Madison noted that New Jersey was absent for the first three votes, but present and voting later. Someone was temporarily absent. Madison recorded Massachusetts absent for the seventh vote. This also must have been a temporary absence. Maryland was evenly divided on the third vote. Georgia was divided on the final vote of the day.

Butler and Pinckney from South Carolina wanted the provision concerning the flight from justice in one state to be extended to slaves who fled for freedom. They moved “to require fugitive slaves and servants to be delivered up like criminals.” Reheard Article IV, Section 2 (giving Legislature authority to establish property qualification for members). Motion by Pinckney to spell out property qualifications in the Constitution rejected on voice vote. Pinckney suggested $100,000 for President and $25,000 for representatives. “The motion of Mr. Pinckney was rejected by so general a no, that the States were not called.” Reconsidered (6 – 5) House residence requirement in Article IV, Section 2, and substituted three years for seven at request of Wilson objected as a matter of principle. Sherman did not want to deal with the issue of fugitive slaves as extradited criminals. According to Madison: “Mr. Butler withdrew his proposition in order that some particular provision might be made apart from this article.”

Where did Butler’s idea come from? The answer is the Confederation Congress meeting in New York on July 14, 1787. The Congress agreed to prohibit slavery in the Northwest Territories at once — 1787 — rather than 1800 in exchange for a Fugitive Slave Clause. And thus the Northwest Ordinance was passed.

August 29: Articles XVI-XVII deliberated

Took up Article XVI (full faith and credit). Heard motion to establish uniform bankruptcy laws. Committed both Article XVI and motion to Committee on State Commitments with 5 members, chaired by John Rutledge.

Took up recommendation by the Livingston Committee on Slave Trade to strike out Article VII, Section 6 (2/3 vote needed to approve Congressional regulation of international and interstate commerce). Committee report approved (7 – 4).

Returned to Article XV and passed a fugitive slave clause (11 – 0) to be added at the end of the Article: “if any Person bound to service or labor in any of the United States shall escape into another State, he or she shall not be discharged from such service or labor in consequence of any regulations subsisting in the State to which they escape; but shall be delivered up to the person justly claiming service or labor.”

Took up Article XVII (admission of new states) and passed (6 – 5).

There were five recorded votes on this day. Eleven states voted.

Madison wrote a footnote on General Pinckney’s remark about “the liberal conduct” of the “Eastern States towards the view of South Carolina.” Pinckney “meant the permission to import slaves. An understanding on the two subjects of navigation and slavery, had taken place between those two parts of the Union.”

Butler introduced a revised version of the Fugitive Slave Clause separate from the extradition clause, and the world “criminal” was dropped. This passed 11-0.

If the Congressional veto over state legislation has been defeated and replaced by the supremacy clause, who enforces it? The answer is the federal judiciary.

Why did the slavery clauses of the Committee of Detail Report generate the most opposition of any clauses in the August 6 draft of the Constitution? How come the South Carolina delegates, and following their lead, the delegates from North Carolina and Georgia, manage to leverage their minority numerical position to extract concessions from the majority of the delegates and the majority of the states in attendance?

Madison’s argument on June 6 is that they needed to create a Constitution that will control the tyrannical conduct of the majority including, but not limited to, the tyrannical conduct of a majority. “In the most enlightened period” of all time, we see the rule of the majority over a minority based on “the mere distinction of color.”

Scene 3: Adoption of the Report; Creation of Brearly Committee

August 30: Articles XVII-XXI adopted

There were 15 recorded votes on this day. Eleven states voted. Maryland missed the eleventh vote, but was present for all the others. North Carolina missed the seventh vote, but was present for all the other votes. Delaware voted; Read was present rather than probably present.

Continued discussion on Article XVII (admission of new states). Agreed (8 – 3) to permit the admission of new States on equal terms, prohibit dividing or combining states without consent of State Legislatures, and grant Congress authority to govern public lands, territory or other property of the United States.

Took up Article XVIII (guarantee of republican form of government): “The United States shall guaranty to each State a Republican form of Government; and shall protect each State against foreign invasions, and, on the application of the Legislature, against domestic violence.” Dropped “foreign” and retained “domestic violence” over “insurrection” (6 – 5). Amended and agreed (9 – 2).

Took up Article XIX (amending process) and agreed.

Took up Article XX (oath for officers of the government). Added “or Affirmation.” Added, “no religious test shall ever be required,” which passed nem con. Agreed (8 – 1 – 2) to Article XX.

Discussed Article XXI (mode of ratification of the Constitution): “The ratification of the Conventions of ____ States shall be sufficient for organizing this Constitution.”

August 31: Discontent within Agreement

There were 15 recorded votes on this day, the last day of Act III. Ten states voted on the first motion and eleven states voted on all of the other motions. Delaware missed the first vote. Massachusetts was absent for the last vote, but present for the preceding votes. North Carolina was absent for the fourth and fifth vote, but present for the other 13 votes. Connecticut was divided on the second vote and Maryland was divided on the fourteenth vote.

“The Leftovers Committee,” or Brearly Committee of “Postponed Parts,” was selected, one delegate from each of the 11 states. The composition of this committee, and the desire to come to a workable compromise, once again depicts the shifting disposition of the delegates to the Convention over the long haul of the deliberations.

The presence of Sherman, Brearly, Dickinson, Carroll, and Baldwin meant that the State Legislatures would be centrally involved in the election of the President. They were important delegates in the creation and passage of the partly national, partly federal Connecticut Compromise that settled the controversy over popular representation and the equal representation of state. Even with the absence of New York, the old New Jersey Coalition of June was still alive and well and could point to the precedent of the Connecticut Compromise — even though the internal composition of the Coalition had changed.

Continued discussing Article XXI (mode of ratification of the Constitution). Shall the blank be filled with the number 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 or 13? Agreed (9 – 1), to add “between the said states,” to limit the effect of ratification to states actually ratifying. Rejected (6 – 4) attempt to overturn provision requiring ratification by specially elected conventions rather than ratification by State Legislatures. Debated number of states required to secure ratification of the Constitution.

Defeated (9 – 1) motion requiring all 13 states to ratify. Defeated (7 – 4) motion requiring 10 states to ratify. Agreed (8 – 3) to motion requiring 9 states to ratify. Agreed (10 – 1) to Article XXI as amended.

Took up Article XXII (Authorization of the Constitution by Confederation Congress). Agreed (8 – 3) to strike provision requiring Confederation Congressional approval of the Constitution. Defeated (7 – 4) proposal, in effect, permitting Confederation Congress to rewrite the Constitution. Defeated (8 – 3) motion to postpone discussion on Article XXII. Agreed (10 – 1) to Article XXII as amended.

Discussed Article XXIII (transition from Confederation Government to Constitutional Government). Agreed with amendments.

Took up Committee of 11 Report of Article VII, Section 4 (Export taxes and duties). Agreed to provision not to give preference to one state over another. Agreed (8 – 2) to proposal to prohibit requiring ships bound for one state to enter, clear, or pay duties in another. Agreed on uniformity clause.

Concluded discussion of Committee of Detail Report.

Referred all leftover proposals to a Committee of one delegate from each state: Gilman, King, Sherman, Brearly, G. Morris, Dickinson, Carroll, Madison, Williamson, Butler, Baldwin. This was known as the Brearly Committee.