The Constitutional Convention: Act IV, The End is in Sight

Scene 1: The Brearly Committee Report

September 1: The Final Push

One vote recorded, namely, to adjourn! (7-1-1) Nine States present. New Jersey and Pennsylvania absent. New Hampshire divided.

Heard initial report from Brearly Committee.

Discussed alteration in Article VI , Section 9 (Ineligibility of Federal Legislators to other Federal offices).

Also, received the report of the August 29th Committee, the Rutledge Committee. Recommended alteration in Article XVI, concerning bankruptcies. Appearance of “Full Faith and Credit clause.”

September 3: Article XVI revisited

There were eight recorded votes. Maximum of 10 states present. New Hampshire absent for first vote. New Jersey absent on final vote. Delaware absent for all votes. Georgia divided on final two votes.

Took up Article XVI (Full Faith and Credit clause). Agreed to the clause (6 – 3). Uniform bankruptcy laws agreed to (9-1). Connecticut “no.”

Took up Article VI, Section 9 (ineligibility of Federal Legislators to other Federal offices). Agreed (5 – 3 – 1) to Article VI, Section 9. New Jersey not voting, Georgia divided.

September 4: Brearly Committee reports 9 propositions

Luther Martin left the convention and did not return. Delegates discussed four out of nine proposals submitted by Brearly Committee. There were three recorded votes. Two were to postpone and one was to adjourn in order to reflect on the Brearly Committee proposals.

Approved Brearly Committee Proposal #1 to amend Article VII, Section 1 giving Federal Legislature authority to lay and collect taxes, duties and imposts and provide for “the common defense and general welfare.”

Agreed, nem. con., to Proposal #2 to amend Article VII, Section 1, interstate commerce clause, to include Congressional regulation of commerce “with the Indian tribes.”

Postponed Proposal #3 to amend Article IX, Section 1. The Proposal read: “The Senate of the United States shall have the power to try all impeachments; but no person shall be convicted without the concurrence of two thirds of the members present.”

Took up Proposal #4 to amend Article X, Section 1 (Election of Executive).

A.) The Executive and the Vice President, “shall hold …office during the term of 4 years.”

B.) “Each state shall appoint in such a manner as its Legislature shall direct, a number of electors equal to the whole number of Senators and members of the House of Representatives, to which the State may be entitled in the Legislature.”

C.) “The person having the greatest number of (Electoral College) votes shall be the President.”

D.) “If no person have a majority, then from the 5 highest on the list the Senate shall choose by ballot the President.”

E.) “And in every case after the choice of the President, the person having the greatest number of votes shall be vice-president: but if there should remain two or more who have equal votes, the Senate shall choose from them the vice-president.”

F.) “The Legislature may determine the time of choosing and assembling the Electors, and the manner of certifying and transmitting their votes.”

Sherman argued that the point to this clause was “to render the Executive independent of the legislature.” Randolph and Pinckney wanted an “explanation and discussion of the reasons for changing the mode of electing the Executive.” G. Morris gave six reasons and emphasized that the “principal advantage aimed at was that of taking away the opportunity for cabal.” According to Wilson: “the subject has greatly divided the House, and will also divide people out of doors. It is in truth, the most difficult of all on which we have had to decide.”

Received Proposal #5: Qualifications for President including a “natural born Citizen” clause. Received Proposal #6: The Vice-President clause. Received Proposal #7: Advice and Consent of the Senate clause. Received Proposal #8: Opinion in Writing clause. Received Proposal #9: Removal from Office clause.

Approved (7 – 3) a motion to postpone consideration of Proposals #4-9. Connecticut, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania “no.” North Carolina temporarily absent.

September 5: Brearly Committee reports 5 more propositions

Eight recorded votes. Eleven states voted. Considered Proposals #10-11 and #13-14 to amend Committee of Detail Article VII, Section 1.

#10: Added “and grant letters of marquee and reprisal” to the war powers clause, nem con.

#11: Limited military appropriations to two years, nem con.

#13: Granted exclusive jurisdiction over Federal land to Congress, nem con.

#14: Provided limited patents to promote science and arts, nem con.

Agreed (9 – 2) to postpone Proposal #12 concerning Article IV, Section 5: yet another reconsideration of the money bills “glue”of the Connecticut Compromise.

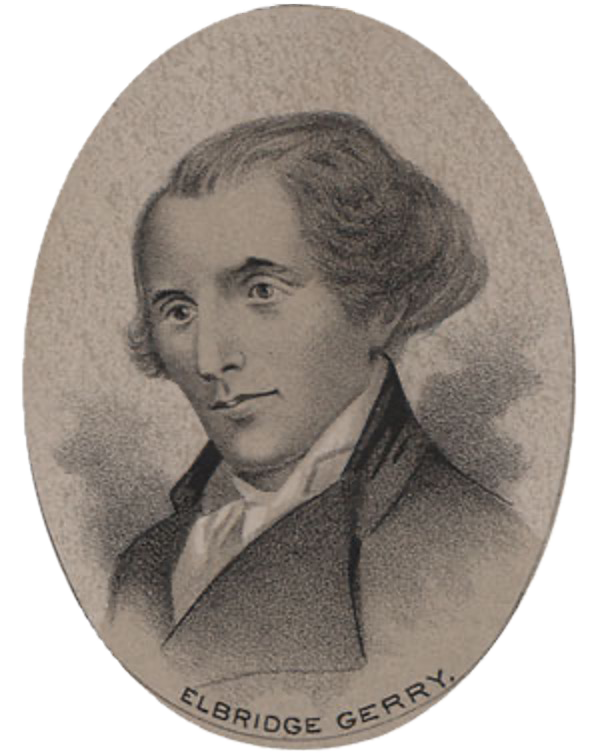

Gerry gave notice that he wanted to reconsider Articles XIX (amending), XX (oath), XXI (ratification), and XXII (blessing of Confederation Congress) of the Committee of Detail Report.

Returned to consideration of the 6 proposals left over from the September 4th submission of 9 proposals by the Brearly Committee (#4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9).

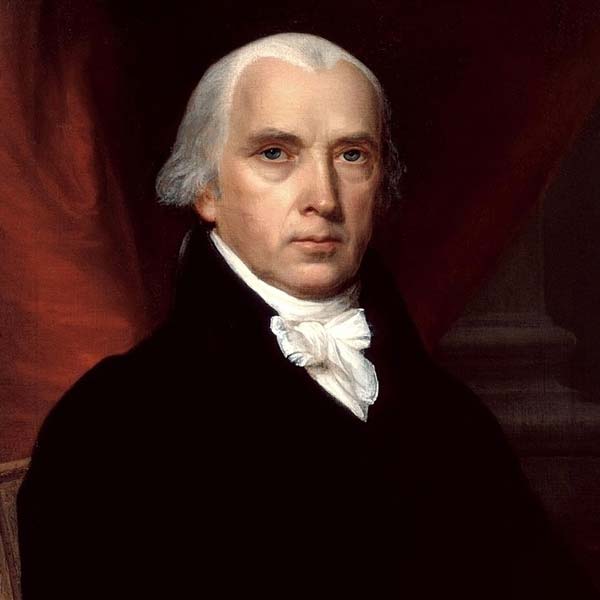

Extensive discussion of Proposal #4 to amend Article X, Section 1 (election of Executive). Madison “considered it as a primary object to render an eventual resort to any part of the Legislature improbable. Randolph: “We have in some revolutions of this plan made a bold stroke for monarchy. We are now doing the same for an aristocracy.” Defeated several motions concerning the election of the Executive.

Defeated (7 – 3 – 1) motion to overcome non-majoritarian outcomes in the Electoral College in the whole Congress instead of just the Senate.

Defeated (9 – 2) motion to limit choice in the Senate to the top 3 candidates instead of the top 5 candidates.

Agreed to request Congress to pay Convention expenses

September 6: Brearly Committee and the Electoral College

There were 20 recorded votes. Eleven States present.

Continued discussion of proposal #4 to amend Article X, Section 1 (election of Executive).

Agreed (10 – 1) that the President and Vice-president be elected to a term of four years.

Agreed (10 – 1) after discussion and amending to authorize the Senate to choose the Executive from top 4 candidates.

Agreed (10 – 1) to a motion by Williamson to substitute the House, with voting by states, for the Senate, or the whole Legislature, in electing the Executive from the top 4 candidates in the event of a break down of the Electoral College. Mason liked this move because it reduced “the aristocratic influence of the Senate.”

Agreed Senate shall choose the Vice-president in the event of a tie for the Vice-president.

September 7: Discussion on the Presidency

Eleven recorded votes. Eleven States present except for North Carolina on the second vote.

Continued discussion of Brearly Proposal #4 to amend Article X, Section 1 (election of Executive). G. Morris: “the Vice President then will be the first heir apparent that ever loved his father.” Mason preferred a Privy Council to having a Vice President. Agreed (8-3) on Electoral College with majority of electoral votes needed for the election of the Executive. Maryland, South Carolina, and Georgia “no.” Decided (10-1) that the House, rather than the Senate, shall decide in the event that the “Electoral College” breaks down, but each state shall have one vote. Pennsylvania disagreed. Approved (6 – 4 – 1) motion to let Legislature determine who shall act in cases of disability of President and Vice President. New Hampshire divided.

Took up Proposal #5: qualifications of the President. Agreed (nem con) that the President should be a natural born citizen, resident for 14 years and be 35 years of age.

Took up Proposal #6: Vice-president as President of Senate. Agreed (8 – 2) to Vice-president as President of the Senate. North Carolina not voting. New Jersey and Maryland “no.”

Took up proposal #7: powers of the Executive. Defeated (10 – 1) motion to include House in treaty making. Pennsylvania disagreed. Agreed to Presidential nomination and Senate concurrence of ambassadors, ministers, consuls, and other officers. Approved treaty making with “the advice and consent” of 2/3 of Senate present. Defeated (8 – 3) motion for Council of Advisors to President. Madison said that in rejecting a Council to the President we were about to try an experiment on which the most despotic governments had never ventured.”

September 8: Treaties, Impeachment, and Money Bills

Eighteen recorded votes. Eleven States voted. Connecticut divided on the second vote.

Resumed discussion on Brearly Proposal #7 (the powers of the Executive). Reconsidered treaty power and engaged in lengthy discussion of role of the Senate especially the 2/3 approval rule. Defeated (6 – 5) Sherman’s motion that “no Treaty be made without a majority of the whole number of the Senate.”

Agreed (8 – 3) to Brearly Committee Proposal #8 (President can request opinions of government officials in writing).

Took up Proposal #9: impeachment of the President. Mason supported by Gerry wanted to add “maladministration” to “treason and bribery.” Madison responded: “So vague a term will be equivalent to tenure during pleasure of the Senate.” Agreed (8 – 3) to replace “maladministration” with “other high crimes and misdemeanors against the State” and then “United States.” New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Delaware “no.” Defeated (9 – 2) motion to strike Senate as body to judge on impeachment. Agreed (11 – 0) to addition of Vice-president and other Civil Officers as subject to impeachment.

Returned to Proposal #12: Consideration of Money Bills. Agreed (9 – 2) to Proposal #12 (origination of money bills in the House, subject to Senate amendment). This vote removes that feature of the Connecticut Compromise deemed vital by Mason, Gerry and Randolph.

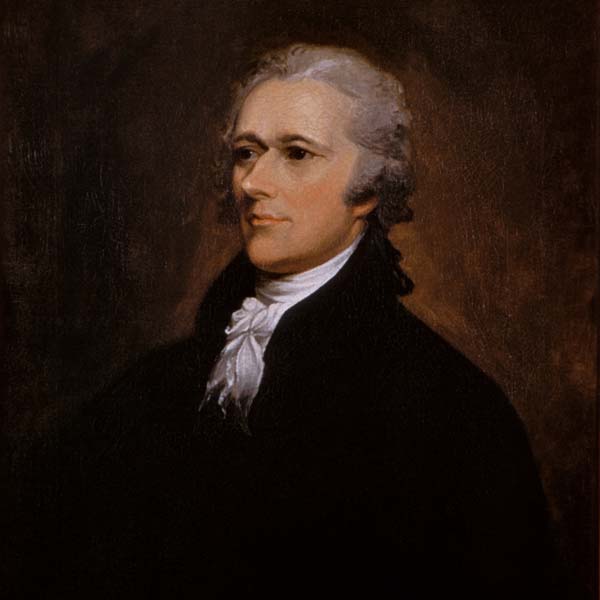

Balloted for a Committee of Style (Johnson, Hamilton, G. Morris, Madison, and King) “to revise the style of and arrange the articles which had been agreed to.” Note, as in the case of the membership on the Committee of Detail a delegate from Connecticut, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and Massachusetts were chosen. Who would be the extra this time? “], Hamilton could not vote on the floor of the House because New York was not “officially” present. Yet, he was elected by the Convention delegates to the Committee of Style!

Defeated (6 – 5) motion supported by Madison and Hamilton to increase the size of House membership.

September 10: Randolph articulates his difficulties

Eight recorded votes. Eleven States present. New Hampshire divided on four votes.

Reconsidered (9 – 1 – 1) Article XIX of the Committee of Detail report: Process to Amend the Constitution (2/3 of state legislatures requesting an amendment, the Congress shall call a Convention). New Jersey “no;” New Hampshire divided. Madison wondered: “How was a Convention to be forced? By what rule decide? What is the force of its acts?” Agreed (9 – 1) to permit 2/3 House and 2/3 Senate to request an amendment and 3/4 of the states to approve. Agreed (11 – 0) that an amendment proposal becomes part of the Constitution upon ratification of 3/4 of the State Legislatures or State Conventions. Rutledge “never could agree to give a power by which the articles relating to the slaves might be altered by the States not interested in that property and prejudiced against it.” He secured exclusion of any alteration in the slavery provisions from the amendment process until the year 1808.

Agreed (7 – 3 – 1) to reconsider Article XXII of the Committee of Detail Report. Pennsylvania “no.”

Approved (11 – 0) Article XXI. This Constitution becomes effective on the approbation of 9 state ratifying conventions and “binding and conclusive” on those states “assenting thereto.”

Randolph took this opportunity to state 12 “objections to the system.” Randolph and Gerry explain their reservations about signing the Constitution “if approbation by Congress” isn’t required. Delegates rejected nem con a motion to require the approval of the Constitution by the Confederation Congress.

Committee of Detail Report, as revised, and Brearly Committee report, as revised, sent to the Committee of Style.

Scene 2: The Committee of Style Report – A Preamble and 7 Articles

September 11: How about this and how about that?

Convention met and adjourned because the Committee of Style was not ready with their report.

The five people elected to the Committee of Style showed yet another swing in the deliberate sense of the Convention. The delegates, in the last stages of the Convention, were willing to give a privileged position in providing the “final touches” of the Constitution to such consistently “high-toned” delegates as King, Hamilton, G. Morris, and Madison. I find this remarkable. The fifth delegate chosen, and also the chair of the Committee of Style, was (Johnson of Connecticut. The “high toners” today have been given, by the entire Convention, the opportunity to put an original Virginia Plan stamp back on the final product. Interestingly, there was one delegate from Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, Virginia, Connecticut, and one left over. In July, it was Rutledge from South Carolina. Today, it was Hamilton from New York.

September 12: Is this different from Committee of Detail Report?

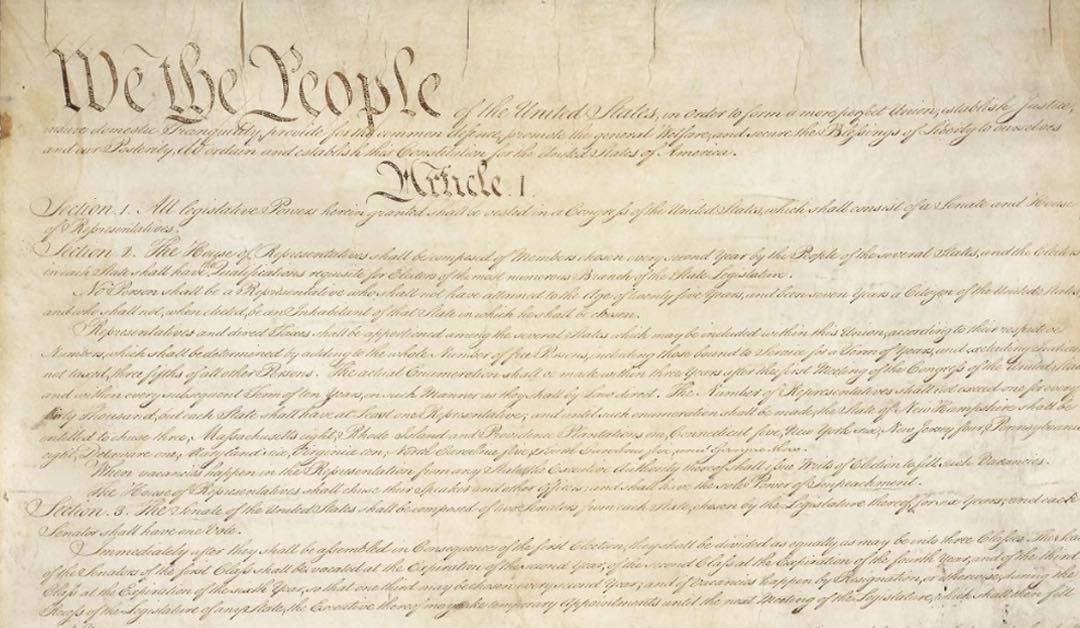

Four recorded votes. Eleven states present on the first vote. Massachusetts absent for the last three votes. Committee of Style reported a 7 Article document; it was read by paragraphs. This document is preceded by a preamble, which begins, “We the People of the United States, in order to form a more perfect union” rather than “We the people of the states of New Hampshire, etc…”

Took up Article I, Section 7. Agreed (6 – 4 – 1) to amend section to include 2/3 instead of 3/4 for Congress to override an Executive veto.

Mason and Gerry call for a prefatory Bill of Rights. Mason wished the plan “had been prefaced with a Bill of Rights… It would give quiet to the people; and with the aid of the State declarations, a bill might be prepared in a few hours … The Laws of the US are to be paramount to State Bills of Rights.” Motion is defeated (10 – 0). Massachusetts temporarily absent.

In early September, as we have seen, the Virginia delegates divided over ratification procedures more than did the Convention as a whole. Should ratification be by state legislatures or state conventions elected by the people, and then how many should say “yes” for ratification? What is to be the role of these conventions? Can they propose amendments or must they just vote “up or down?” What about the role of the existing Congress? Must they approve the proposals and can they make alterations? Should there be a Second Grand Convention where all these things are pulled together?

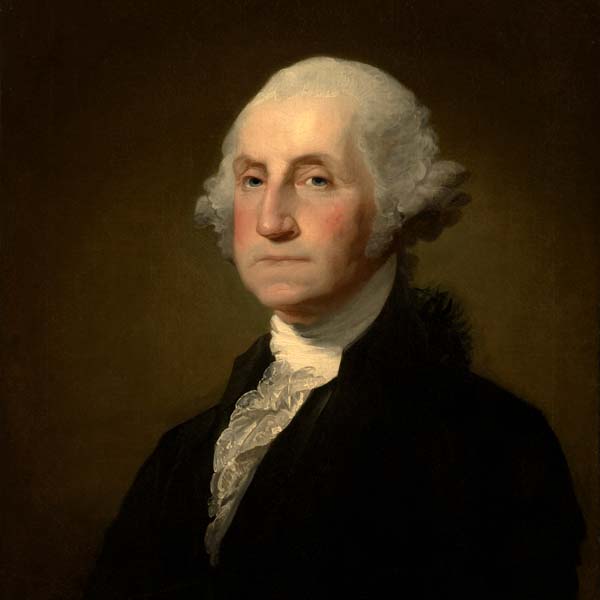

On September 12, the Virginia delegation disagreed on whether to substitute a 2/3 Congressional override of a Presidential veto for the proposed 3/4 override requirement in Article I , Section 7 of the Committee of Style Report. Madison provides detail. “On the question to insert 2/3 in place of 3/4,” writes Madison, the measure passed 7-3-1. “New Hampshire divided. Virginia no … General Washington, Mr. Blair, Mr. Madison no. Col. Mason, Mr. Randolph ay.” Again, Washington wasn’t reluctant to participate, and, it should be noted, even in such a delicate matter as the independence, and centrality, of the Presidency. The 3/4 override was changed in the last days of the Convention to 2/3, but this does not alter the fact that Washington could be active AND he could be defeated.

This second vote concerned the call for the adoption of a bill of rights by Gerry and Mason. The latter “wished the plan had been prefaced with a Bill of Rights, and would second a motion if made for that purpose — it would give great quiet to the people; and with the aid of the State declarations, a bill might be prepared in a few hours.” And a federal bill of rights was necessary, he added, because “the laws of the U.S. are to be paramount to State Bills of Rights.” The motion was defeated (0-10-1). Massachusetts absent. Gorham spoke just before the motion and Gerry supported the motion. King did not speak today. So King is probably the absent one from Massachusetts thus making Massachusetts absent.

Scene 3: The Discussion of the Committee of Style Report

September 13: Last minute additions

Eleven votes recorded. Ten states voted on the first three motions. Massachusetts absent for motions 1-3. Eleven states voted on the remaining seven motions.

Resumed consideration of Report of Committee of Style.

Took up Article I and focused on Sections 2 and 7. Agreed unanimously to substitute “service” for “servitude.” The delegates agreed with Randolph, that “servitude” expressed “the condition of slaves.” Agreed (7-3) to allow state duties to defray costs of storage and inspection.

Mason bemoaned the absence of “a power to make sumptuary regulations.” Mason, Franklin, Dickinson, Johnson, and Livingston selected to a committee to suggest measures for encouraging economy, frugality, and American manufactures. This committee never made a report.

Johnson from the Committee of Style reported a substitute for Articles XXII and XXIII of the Committee of Detail Report.

September 14: The Necessary and Proper clause

Eighteen recorded votes. Eleven states voted, except New Hampshire did not vote on the final motion. South Carolina and Connecticut divided on this day.

Took up Article I, Sections 3, 4, 5, and 6. Agreed to sections with minimal debate.

Took up Article I, Section 8 (Powers of Congress). Agreed (8 – 3) to strike election of Treasurer by Legislature. Agreed (11 – 0) to add uniformity requirement to taxing power. Madison, Randolph, Wilson, G. Morris, and Mason debate meaning of “necessary and proper clause.” Defeated (6 – 4 – 1) motion by Madison and Pinckney to give Congress power to establish a university “in which no preferences or distinctions should be allowed on account of religion.” G. Morris argued, that “it is not necessary. The exclusive power of the Seat of Government, will reach the object.” Connecticut divided. Pennsylvania, Virginia, South Carolina, and Georgia voted that it was necessary.

Pinckney, Gerry, and Sherman debate whether Congress has the power to interfere with freedom of the press. According to Sherman: “it is unnecessary. The power of Congress does not extend to the press.” Defeated (6-5) motion to insert “the liberty of the press shall be inviolably preserved.”

Took up Article I, Section 9 (Restraints on Congressional powers). Defeated Mason’s motion “that an account of the public expenditures should be annually published.” Adopted Madison’s suggestion nem con to change “annual” publications to “from time to time.” Agreed to the Section with minimal debate.

Took up Article I, Section 10 (Restraints on the powers of the States). Gerry’s motion to extend to the Federal Government “the restraint put on the states from impairing the obligations of contracts” failed to obtain a second.

September 15: How about a Second Convention?

Sixteen recorded votes on this day. Eleven states were present and voted except on the first, when South Carolina was absent, and the eleventh and remaining votes when North Carolina was absent. Connecticut was divided twice. Pennsylvania was divided on the second and fifth vote. Delaware was divided on the eleventh vote. Maryland was also divided on the eleventh vote.

The delegates discussed the Interstate Commerce Clause in Article I, Section 8, the restraints on the states in Article I, Section 10, and turned their attention to the Presidency in Article II, and the amendment process in Article V. The Convention resumed discussion on the Report from the Committee of Style.

Decided (6 – 4) an address from the Convention to the people was “unnecessary and improper.” South Carolina absent.

Defeated (6 – 5) an attempt to add another member for Rhode Island in the House. King: “he never could sign the Constitution” if this were passed. Passed (10 – 1) an attempt to add another member for North Carolina in the House.

Took up Article I, Section 10 (restraints on the powers of the States). Madison argued that this depends on the extent of the Interstate Commerce Clause. McHenry, Carroll, Langdon, Mason, G. Morris, Madison’s and Sherman debate the meaning of the interstate commerce clause. Does the regulatory power of Congress restrain state commerce authority? Agreed (6 – 4 – 1) that “no state shall lay any duty on tonnage with out the consent of Congress.” Connecticut divided.

Took up Article II, Section 1 (General structure of Executive Office). Agreed (7 – 4) that the President shall not receive “any other emolument from the United States or any of them” during his term of office.

Took up Article II, Section 2 (Powers of the President). Defeated (8 – 2 – 1) a motion to extend the power “to grant reprieves and pardons for offenses against the United States, except in cases of impeachment” to include “cases of treason.” Connecticut divided.

Agreed (after debate, nem con) to G. Morris’s “Inferior Officer’s” clause (Allows Congress to by pass the “advice and consent of the Senate” and vest/delegate the appointment of “inferior officers” to the President alone, the Courts of Law alone or the Heads of Departments alone). This motion was initially defeated (5 – 5 – 1).

Took up Article III, Section 2 (Trial by jury). Defeated (nem con) an attempt to extend the “trial by jury” clause covering criminal cases to include civil cases.

Took up Article IV, Section 2 (Fugitive Slave clause). Struck out “no person legally held to service or labor in one state escaping into another” and replaced it with “no person held to service or labor in one state, under the laws thereof, escaping into another” (emphasis added). Addition of “under the laws thereof” removes the idea “that slavery was legal in a moral view.”

Agreed to Article IV, Section 3 (Admittance of new states).

Agreed to Article IV, Section 4 (Republican guarantee).

Took up Article V (Amending the Constitution). Agreed (nem. con.) that Congress shall call a convention on the application for amendments by 2/3 of the State Legislatures. Sherman “thought it reasonable that the proviso in favor of the States importing slaves should be extended so as to provide that no State should be affected in its internal police, or deprived of its equality in the Senate.”Agreed (8 – 3) to the motion of G. Morris that a state cannot be deprived of its equal suffrage in the Senate without its own consent.

Gerry listed seven objections to the Constitution and offered three possible changes. The delegates unanimously rejected a call by Randolph, Mason, and Gerry “that amendments to the plan might be offered by the States Conventions, which should be submitted to and finally decided on by another general convention.”

Approved (10 – 0) the document as amended (North Carolina did not meet quorum call). Washington must have voted with Madison’s and Blair.

On September 15, Mason listed 16 objections. Mason wrote to Washington giving the General a copy of his objections to the Constitution. “Dear General,” began Mason, “you know how much I love you and how we worked together, but my conscience demands that I state my objections, and here they are. No bill of rights, the President may pardon all kinds of people …” Washington then wrote to Madison and said, “You know, I made sure that his letter made it to all the newspapers across the country as a way of demonstrating what an unreliable man George Mason is.”

Scene 4: The Signing of the Constitution

September 17: Constitution signed

There were two recorded votes on this day. Eleven states were present and voted. The delegation — as distinct from the individual delegates — agreed on singing the Constitution and also agreed “to deliver the journals and papers to the President.”

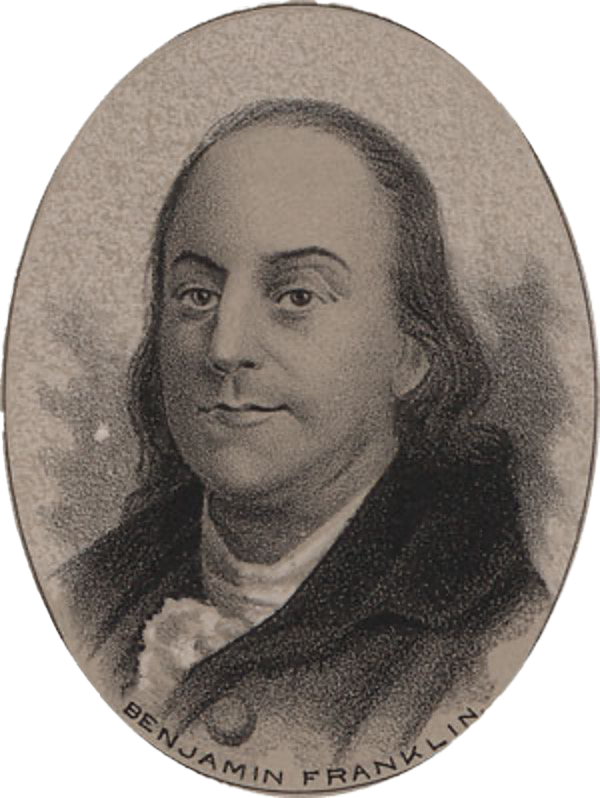

Franklin opened the day with a speech that was used by the pro-constitutionalists in the ratification debate. “I agree to this Constitution with all its faults … I doubt too whether any other Convention we can obtain may be able to make a better Constitution … Sir, I cannot help expressing a wish that every member of the Convention who may still have objections to it, would with me, on this occasion doubt a little of his infallibility — and to make manifest our unanimity, put his name to the instrument.”

Gorham, supported by King and Carroll, hoped “it was not too late” as a way “of lessening objections to the Constitution to substitute 1:30,000 for 1:40,000” by giving Congress “a greater latitude” in securing a reasonable scheme of proportional representation. Washington spoke for the first time at the Convention: “It was much to be desired that the objections to the plan recommended might be as few as possible … Late as the present moment was for admitting amendments, he thought this of so much consequence that it would give satisfaction to see it adopted.”

The delegates unanimously agreed to Gorham’s proposal, but it was not enough to persuade Randolph and Mason and Gerry to sign.

Franklin raised the following practical questions: 1) Isn’t “a more perfect union,” better than “a less perfect union?” 2) Isn’t “a perfect union,” achievable only in speech? Randolph issued the following grim warning as an explanation for his decision: “Nine States will fail to ratify the plan and confusion must ensue.” Gerry feared an impending civil war and considered Franklin’s remarks to be personally motivated.

Franklin also had the last word at the Convention with his “Rising Sun” speech.

Franklin’s optimistic appeal to the improvement of the American condition and Randolph’s pessimistic appeal to the realism of “political arithmetic” marks the end of the Four-Act-Drama of the Convention.

Washington noted in his diary, that “the members adjourned to the City Tavern, dined together and took a cordial leave of each other.”