Washington’s City Tavern Bill

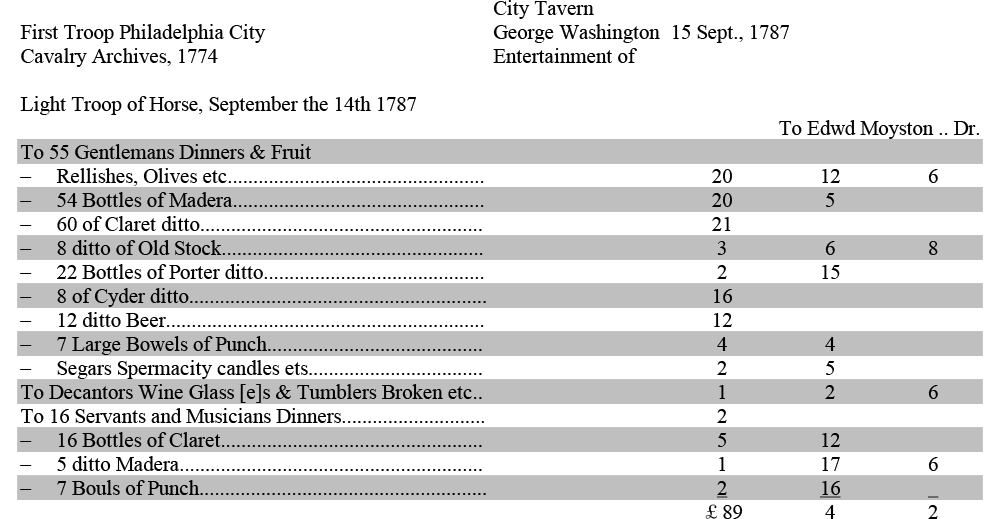

PART ONE: MENU FOR GENTLEMEN AND MUSICIANS

Doug Gammell tells us that £89 in 1780 equals £9693 in 2011. This is obtained by multiplying £89 by the percentage increase in the RPI from 1780-2011. According to xe.com a pound in 2022 is equal to $1.24 U.S. dollars, so in 2022 the meal would cost approximately $20,270.49.

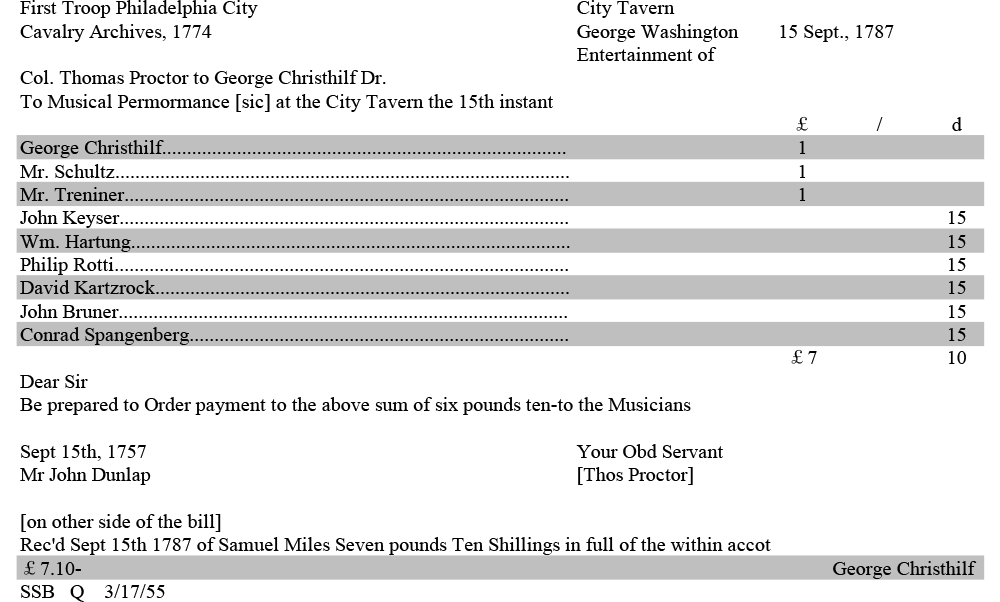

PART TWO: BILL FOR MUSICIANS

PART THREE: REFLECTIONS ON THE CITY TAVERN MENU AND BILL, BY GORDON LLOYD

In 1985, Dr. David Kimball, then the lead historian at Independence Hall, Philadelphia, generously made all his vast collection of transcriptions of original records some typed, others photocopied, many full of notations and scribbles, and still others in his own handwriting available to me as part of a collaborative effort to commemorate the Bicentennial of the Constitution of 1787.

Working through this huge and amazing array of material, I came across the menu and bill for the Farewell Dinner for George Washington on Friday, September 14, 1787 hosted by the First Troop Philadelphia City Cavalry. A related bill for 7 pounds 10 shillings to pay the musicians suggests that the dinner took place on Friday the 14th of September and Thomas Proctor submitted the bill on Saturday the 15th of September.

If this menu and bill for the 14th of September has been preserved, perhaps the menu and bill for the Framers’ Farewell dinner on Monday the 17th of September can be found? Wouldn’t it be lovely if that could be recovered and added to the story of the American Founding? That was what was on my mind as I continued to search through the material.

Neither Kimball nor I were able to locate the menu or bill for the Framers’ Farewell at the City Tavern. And, to the best of my knowledge, no such an item is available. So the menu and bill from the Washington Farewell is the closest we have both in terms of time and possible authenticity.

I don’t claim that the Washington Farewell was duplicated on the 17th of September for the Framers’ Farewell. But the two dates are so close, and both dinners are Farewell dinners, and both involve George Washington. These facts no doubt have been the reasons why literally hundreds of people have requested over the years that I provide them with a copy of the menu and bill. After twenty years of hesitation, I now make the material available to the general public.

The dinner bill for 55 Gentlemen, and 16 Musicians, and Servants, Part One, and the accompanying bill for what appears to be a manager of the musicians (George Christhilf), two lead musicians (Mr. Schultz and Mr. Treniner) and six accompanying musicians, Part Two, reproduces the original, and incorrect spelling, and retains the unidentified notations. For example, “bowls” is spelled two different ways and these incorrect spellings have been retained. So too have the spellings, “Segars,” “Permorance,” and “Cyder.” Also, I have retained the following notations in the bottom left hand corner of Part One of the manuscript: “Musich-[?]”, and underneath that, the initial “SSB” and the date “3/15/55.” Similarly, I have retained the notation “SSB” and “Q” and the date 3/17/55 in the same location for the second bill in Part Two of the manuscript.

Kimball and I presumed that these notations were added to the original record at a later date, presumably in 1955, as part of the effort to commemorate the Bicentennial of the Declaration of Independence.

The word “Musich” probably refers to the accompanying bill that listed the cost “To Musical Permormance” [sic] of £7 and 10 shillings.

Nick Christhilf, family genealogist, informs me that his “G4 grandfather,” George Christhilf, served during the Revolutionary War as a German auxiliary fighting for the British in 1777 while in his early twenties. He was captured, released, and rather than return to Germany, he defected to the United States, and subsequently joined the Philadelphia County Militia in 1784. He lived in the German area between Vine and Race Streets in Philadelphia where he befriended Trenier, Shultz, and Spangenberg, all named in the list of musicians providing entertainment for Washington in 1787. He died in the 1793 Philadelphia yellow fever epidemic.

General Thomas Proctor (1739-1806) submitted the bill; he is buried in Philadelphia, and his grave plaque in Old St. Paul’s Episcopal Church reads: “was a Colonel Commanding the Artillery Under General Washington Revolutionary War.” John Dunlap arrived in Philadelphia from Ireland in 1757 and edited the Philadelphia Packet newspaper, the first newspaper in the United States to publish the Constitution. Samuel Miles (1740-1805) paid the bill; he was a Quaker of Welsh descent who served in the Revolutionary War and, in 1787, was a member of the Council of Censors. The Council was an official body responsible for monitoring violations of the separation of powers in Pennsylvania. Edward Moyston, mentioned on the top right hand side of Part One, the presumed recipient of the bill for the “Gentlemans Dinners,” was a member of the 3rd Company, Second Battalion of the Philadelphia Militia in 1787. (See Pennsylvania Archives, Volume III, 6th Series, pp.1003-1054.)

The letter “£” in the tallying up the bill rows of the two Light Troop of Horse bills, is a symbol for pounds and the other two unidentified columns on the right hand side of the menu and bill represent shillings and pence. Thus the total bill for the “Gentlemans Dinners” came to £89 and 4 shillings and 2 pence. There is nothing to indicate whether this was in British Pounds or some other currency.

According to the historical records in the Archives of the First Troop Philadelphia City Cavalry, on November 17, 1774, twenty-eight prominent citizens of Philadelphia gathered in Carpenter’s Hall and formed the Light Horse of the City of Philadelphia. The purpose of this voluntary association was to devise ways to resist “the British and to carry out the non-importation resolutions of (the First Continental) Congress.” [The name was later changed to First Troop Philadelphia City Cavalry.]

In late 1776, and early 1777, the Light Troop of Horse joined Washington’s Continental Army in crossing the Delaware River and fought at the Battle of Trenton and the Battle of Princeton. They also served at Valley Forge. They led the victory parade through Philadelphia in 1783 and participated at the funeral of George Washington by which time the membership stood at about one hundred.

For a recent–February of 2018–article about the farewell dinner, click here.