Brutus II

November 1, 1787

INTRODUCTION

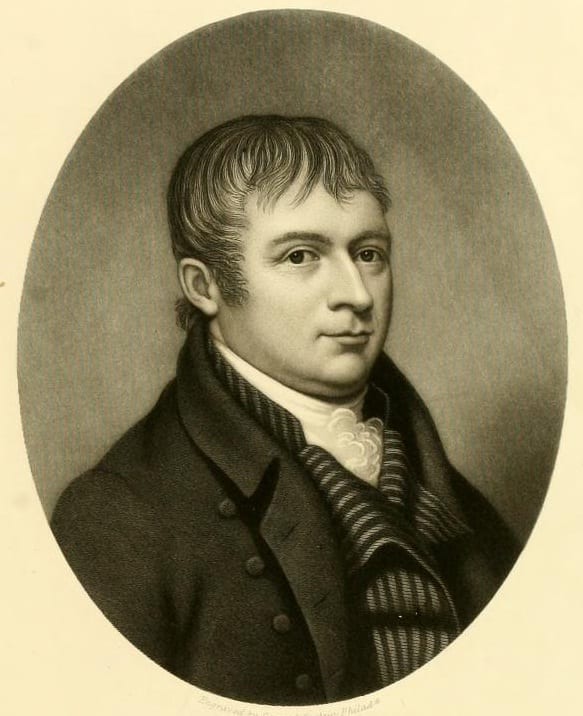

In the second of sixteen essays that he published in the New York Journal, the prominent New York Antifederalist, Brutus (thought by some to be Melancton Smith, an experienced New York politician) concurred with the arguments of George Mason and Richard Henry Lee (Objections at the Constitutional Convention and Letter to Edmund Randolph). There was no doubt in their minds that the new plan of government had the potential to concentrate power in the hands of the few. There was also a remarkable uniformity in the specific individual rights they thought needed protection: rights of conscience, freedom of the press, freedom of association, no unreasonable searches and seizures, trial by jury in civil cases, and no cruel and unusual punishment.

In his second essay, Brutus revisited “the merits” of the argument in his first essay, Brutus I, “that to reduce the thirteen states into one government, would prove the destruction of your liberties.” Again anticipating The Federalist, Brutus argued, “when a building is to be erected which is intended to stand for ages, the foundation should be firmly laid.” But the foundation of the Constitution was poorly laid, he thought, because it lacked a declaration of rights “expressly reserving to the people such of their essential natural rights, as are not necessary to be parted with.” He rejected as “specious” the arguments of an unnamed framer’s State House speech (James Wilson) as to why a bill of rights is unnecessary: after all, “the powers, rights, and authority, granted to the general government by this Constitution, are as complete, with respect to every object to which they extend, as that of any state government.” Furthermore, Brutus asked, why did the framers secure certain rights in Article I, Section 9, “but omitted others of more importance”? This is similar to the appeal to “natural liberty” by Old Whig. What was emerging in this Antifederalist literature was a coherent case for a bill of rights to constrain a potentially runaway national government that would concentrate all power in a district ten miles square.

SOURCE: DEBATES AND PROCEEDINGS OF THE CONVENTION OF THE COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS HELD IN THE YEAR 1788 AND WHICH FINALLY RATIFIED THE CONSTITUTION OF THE UNITED STATES (BOSTON: WILLIAM WHITE PRINTER TO THE COMMONWEALTH, 1856), 378–384;

HTTPS://GOO.GL/DKYHMI

To the Citizens of the State of New York.

I flatter myself that my last address established this position, that to reduce the thirteen States into one government, would prove the destruction of your liberties.

But lest this truth should be doubted by some, I will now proceed to consider its merits.

Though it should be admitted that the argument[s] against reducing all the states into one consolidated government are not sufficient fully to establish this point; yet they will, at least, justify this conclusion that in forming a constitution for such a country, great care should be taken to limit and define its powers, adjust its parts, and guard against an abuse of authority. How far attention has been paid to these objects, shall be the subject of future enquiry. When a building is to be erected which is intended to stand for ages, the foundation should be firmly laid. The Constitution proposed to your acceptance, is designed not for yourselves alone, but for generations yet unborn. The principles, therefore, upon which the social compact is founded, ought to have been clearly and precisely stated, and the most express and full declaration of rights to have been made—but on this subject there is almost an entire silence.

If we may collect the sentiments of the people of America, from their own most solemn declarations, they hold this truth as self-evident, that all men are by nature free. No one man, therefore, or any class of men, have a right, by the law of nature, or of God, to assume or exercise authority over their fellows. The origin of society then is to be sought, not in any natural right which one man has to exercise authority over another, but in the united consent of those who associate. The mutual wants of men, at first dictated the propriety of forming societies; and when they were established, protection and defense pointed out the necessity of instituting government. In a state of nature every individual pursues his own interest; in this pursuit it frequently happened that the possessions or enjoyments of one were sacrificed to the views and designs of another; thus the weak were a prey to the strong, the simple and unwary were subject to impositions from those who were more crafty and designing. In this state of things, every individual was insecure; common interest therefore directed that government should be established in which the force of the whole community should be collected, and under such directions, as to protect and defend every one who composed it. The common good, therefore, is the end of civil government, and common consent, the foundation on which it is established. To effect this end, it was necessary that a certain portion of natural liberty should be surrendered in order that what remained should be preserved: how great a proportion of natural freedom is necessary to be yielded by individuals when they submit to government, I shall not now enquire. So much, however, must be given up, as will be sufficient to enable those to whom the administration of the government is committed to establish laws for the promoting the happiness of the community, and to carry those laws into effect. But it is not necessary for this purpose that individuals should relinquish all their natural rights. Some are of such a nature that they cannot be surrendered. Of this kind are the rights of conscience, the right of enjoying and defending life, etc. Others are not necessary to be resigned in order to attain the end for which government is instituted, these therefore ought not to be given up. To surrender them, would counteract the very end of government, to wit, the common good. From these observations it appears, that in forming a government on its true principles, the foundation should be laid in the manner I before stated, by expressly reserving to the people such of their essential natural rights as are not necessary to be parted with. The same reasons which at first induced mankind to associate and institute government will operate to influence them to observe this precaution. If they had been disposed to conform themselves to the rule of immutable righteousness, government would not have been requisite. It was because one part exercised fraud, oppression, and violence on the other, that men came together, and agreed that certain rules should be formed, to regulate the conduct of all, and the power of the whole community lodged in the hands of rulers to enforce an obedience to them. But rulers have the same propensities as other men; they are as likely to use the power with which they are vested for private purposes, and to the injury and oppression of those over whom they are placed, as individuals in a state of nature are to injure and oppress one another. It is therefore as proper that bounds should be set to their authority, as that government should have at first been instituted to restrain private injuries.

This principle, which seems so evidently founded in the reason and nature of things, is confirmed by universal experience. Those who have governed, have been found in all ages ever active to enlarge their powers and abridge the public liberty. This has induced the people in all countries, where any sense of freedom remained, to fix barriers against the encroachments of their rulers. The country from which we have derived our origin, is an eminent example of this. Their Magna Charta[1] and Bill of Rights[2] have long been the boast, as well as the security, of that nation. I need say no more, I presume, to an American than that this principle is a fundamental one in all the constitutions of our own states; there is not one of them but what is either founded on a declaration or bill of rights, or has certain express reservation of rights interwoven in the body of them. From this it appears that at a time when the pulse of liberty beat high and when an appeal was made to the people to form constitutions for the government of themselves, it was their universal sense that such declarations should make a part of their frames of government. It is therefore the more astonishing that this grand security to the rights of the people is not to be found in this Constitution.

It has been said, in answer to this objection, that such declaration[s] of rights, however requisite they might be in the constitutions of the states, are not necessary in the general Constitution, because “in the former case, every thing which is not reserved is given, but in the latter the reverse of the proposition prevails, and every thing which is not given is reserved.”[3] It requires but little attention to discover that this mode of reasoning is rather specious than solid. The powers, rights, and authority granted to the general government by this Constitution, are as complete, with respect to every object to which they extend, as that of any state government—it reaches to every thing which concerns human happiness—life, liberty, and property are under its control. There is the same reason, therefore, that the exercise of power, in this case, should be restrained within proper limits, as in that of the state governments. To set this matter in a clear light, permit me to instance some of the articles of the bills of rights of the individual states, and apply them to the case in question.

For the security of life, in criminal prosecutions, the bills of rights of most of the states have declared, that no man shall be held to answer for a crime until he is made fully acquainted with the charge brought against him; he shall not be compelled to accuse, or furnish evidence against himself—the witnesses against him shall be brought face to face, and he shall be fully heard by himself or counsel. That it is essential to the security of life and liberty, that trial of facts be in the vicinity where they happen. Are not provisions of this kind as necessary in the general government, as in that of a particular state? The powers vested in the new Congress extend in many cases to life; they are authorized to provide for the punishment of a variety of capital crimes, and no restraint is laid upon them in its exercise, save only that “the trial of all crimes, except in cases of impeachment, shall be by jury; and such trial shall be in the state where the said crimes shall have been committed.”[4] No man is secure of a trial in the county where he is charged to have committed a crime; he may be brought from Niagara to New York, or carried from Kentucky to Richmond for trial for an offence supposed to be committed. What security is there that a man shall be furnished with a full and plain description of the charges against him? That he shall be allowed to produce all proof he can in his favor? That he shall see the witnesses against him face to face, or that he shall be fully heard in his own defense by himself or counsel?

For the security of liberty it has been declared, “that excessive bail should not be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel or unusual punishments inflicted—that all warrants, without oath or affirmation, to search suspected places, or seize any person, his papers or property, are grievous and oppressive.”[5]

These provisions are as necessary under the general government as under that of the individual states; for the power of the former is as complete to the purpose of requiring bail, imposing fines, inflicting punishments, granting search warrants, and seizing persons, papers, or property, in certain cases, as the other.

For the purpose of securing the property of the citizens, it is declared by all the states, “that in all controversies at law, respecting property, the ancient mode of trial by jury is one of the best securities of the rights of the people, and ought to remain sacred and inviolable.”[6]

Does not the same necessity exist of reserving this right, under this national compact, as in that of these states? Yet nothing is said respecting it. In the bills of rights of the states it is declared, that a well regulated militia is the proper and natural defense of a free government—that as standing armies in time of peace are dangerous, they are not to be kept up, and that the military should be kept under strict subordination to and controlled by the civil power.

The same security is as necessary in this Constitution, and much more so; for the general government will have the sole power to raise and to pay armies, and are under no control in the exercise of it; yet nothing of this is to be found in this new system.

I might proceed to instance a number of other rights, which were as necessary to be reserved, such as that elections should be free, that the liberty of the press should be held sacred; but the instances adduced are sufficient to prove that this argument is without foundation. Besides, it is evident, that the reason here assigned was not the true one, why the framers of this Constitution omitted a bill of rights; if it had been, they would not have made certain reservations, while they totally omitted others of more importance. We find they have, in the ninth section of the first article, declared, that the writ of habeas corpus shall not be suspended, unless in cases of rebellion—that no bill of attainder or ex-post facto law shall be passed—that no title of nobility shall be granted by the United States, &c. If every thing which is not given is reserved, what propriety is there in these exceptions? Does this Constitution anywhere grant the power of suspending the habeas corpus, to make ex-post facto laws, pass bills of attainder, or grant titles of nobility? It certainly does not in express terms. The only answer that can be given is that these are implied in the general powers granted. With equal truth it may be said that all the powers, which the bills of right guard against the abuse of, are contained or implied in the general ones granted by this constitution.

So far it is from being true, that a bill of rights is less necessary in the general Constitution than in those of the states, the contrary is evidently the fact. This system, if it is possible for the people of America to accede to it, will be an original compact; and being the last will, in the nature of things, vacate every former agreement inconsistent with it. For it being a plan of government received and ratified by the whole people, all other forms, which are in existence at the time of its adoption, must yield to it. This is expressed in positive and unequivocal terms, in the sixth article, “That this constitution and the laws of the United States, which shall be made in pursuance thereof, and all treaties made, or which shall be made, under the authority of the United States, shall be the supreme law of the land; and the judges in every state shall be bound thereby, any thing in the constitution, or laws of any state, to the contrary notwithstanding.

“The senators and representatives before-mentioned, and the members of the several state legislatures, and all executive and judicial officers, both of the United States, and of the several states, shall be bound, by oath or affirmation, to support this constitution.”[7]

It is therefore not only necessarily implied thereby but positively expressed that the different state constitutions are repealed and entirely done away, so far as they are inconsistent with this, with the laws which shall be made in pursuance thereof, or with treaties made, or which shall be made, under the authority of the United States; of what avail will the constitutions of the respective states be to preserve the rights of its citizens? Should they be plead, the answer would be, the Constitution of the United States and the laws made in pursuance thereof is the supreme law, and all legislatures and judicial officers, whether of the general or state governments are bound by oath to support it. No privilege reserved by the bills of rights, or secured by the state government, can limit the power granted by this or restrain any laws made in pursuance of it. It stands therefore on its own bottom, and must receive a construction by itself without any reference to any other—and hence it was of the highest importance that the most precise and express declarations and reservations of rights should have been made.

This will appear the more necessary, when it is considered that not only the Constitution and laws made in pursuance thereof, but all treaties made, or which shall be made, under the authority of the United States, are the supreme law of the land, and supersede the constitutions of all the states. The power to make treaties is vested in the president by and with the advice and consent of two thirds of the senate. I do not find any limitation, or restriction, to the exercise of this power. The most important article in any constitution may therefore be repealed, even without a legislative act. Ought not a government vested with such extensive and indefinite authority to have been restricted by a declaration of rights? It certainly ought.

So clear a point is this that I cannot help suspecting that persons who attempt to persuade people that such reservations were less necessary under this Constitution than under those of the states are willfully endeavoring to deceive and to lead you into an absolute state of vassalage.

Footnotes

- A charter signed in 1215 by English barons and King John specifying certain limits on the power of the king.

- An act of Parliament in 1689 that specified limits on the power of the crown

- Document 10

- Constitution, Article III, section 2

- Language taken from amendments to the Constitution proposed at the Virginia ratifying convention.

- North Carolina Constitution

- Also Article VI