Introduction to Out-of-doors Debate

After the signing of the Constitution on September 17th, 1787, a robust debate grew among supporters of the document and those, for various reasons, who were opposed to its ratification as written, or at all. This “out of doors,” to use the language of the times, debate took place in the newspapers, taverns, parlors, and homes of Americans across the 13 states, and served as the public backdrop to the considerations, debates, and eventual decisions of the ratification conventions that would determine the fate of the Constitution and the republic it proposed.

The “out of doors” literature is rich, varied, and immense. On the pro-Constitution side, of course, are the eighty-five essays collectively known as The Federalist. They have acquired an authoritative status virtually equal to the Constitution itself.

But these essays were not the only, or even the most influential, of the pro-Constitution essays. The “Other Federalists” include such heavyweights as James Wilson, Rufus King, Oliver Ellsworth, Roger Sherman, Timothy Pickering, John Marshall, and John Dickinson.

The opponents of the new Constitution (variously described as Anti-Federalists, antifederalists, and our preferred usage, Antifederalists) also wrote a vast and varied literature. Accordingly, this website must be selective in its coverage lest in its efforts to be comprehensive it turns people away because of the enormity of the writing.

The Antifederalist literature is particularly difficult to collect under one accessible roof. For example, no three Antifederalist authors sat down and produced the Antifederalist Papers. And while it is tempting to try to match up individual Antifederalist writings with numbers in The Federalist, this ultimately proves to be a daunting and unproductive exercise. It is far more rewarding to match up major themes than it is to match up individual essays. Thus, Brutus is excellent when it comes to the theme of the Judiciary, as is Cato when the Executive is under consideration. One certainly gets the feel that Hamilton has these two authors in mind when writing the Executive and Judiciary essays. Probably The Federal Farmer writes the best opposition essays on representation in the House and Senate. Again, one gets the impression that Madison was keenly aware of the Federal Farmer essays as he wrote Federalist 55, 56, and 57.

The New York Journal published the sixteen Brutus essays between 18 October 1787 and 10 April 1788. He is presumed to be a New York Antifederalist since, among other things, three quarters of the essays were addressed to the citizens or the people of New York. Robert Yates is the possible author, although Abraham Yates, Thomas Tredwell, and Melancton Smith have also been suggested.

The first five essays are among the best representations of the general Antifederalist critique of the Constitution. Essays six through ten, published in late December and January, cover the legislative branch. The New York Journal also published The Federalist essays 23-26 by Hamilton during this period thus encouraging scholars to see a direct Brutus-Publius confrontation. Five of the last six essays are a critique of the Judiciary and it is probable that Hamilton‘s defense of the independent judiciary in Federalist 78 is a response to Brutus.

The eight letters of Cato were published in The New York Journal between September 1787 and January 1788. The first letter appeared in the 27 September 1787 issue. This issue produced another first: this marked the first time the full text of the Constitution was published in the paper. The presumed author is Governor George Clinton of New York although scholars have disputed his authorship. In the first essay, Cato urges that his readers attach importance to “measures not to men.” Essay three reiterates a familiar Antifederalist critique of Federalist 10: a large and extensive territory is ripe for consolidation and the collapse of republicanism. Cato’s essays are most often associated with his warnings on the Presidency and this is the subject matter of Essay 4. The remaining essays deal with a critique of the House and the Senate.

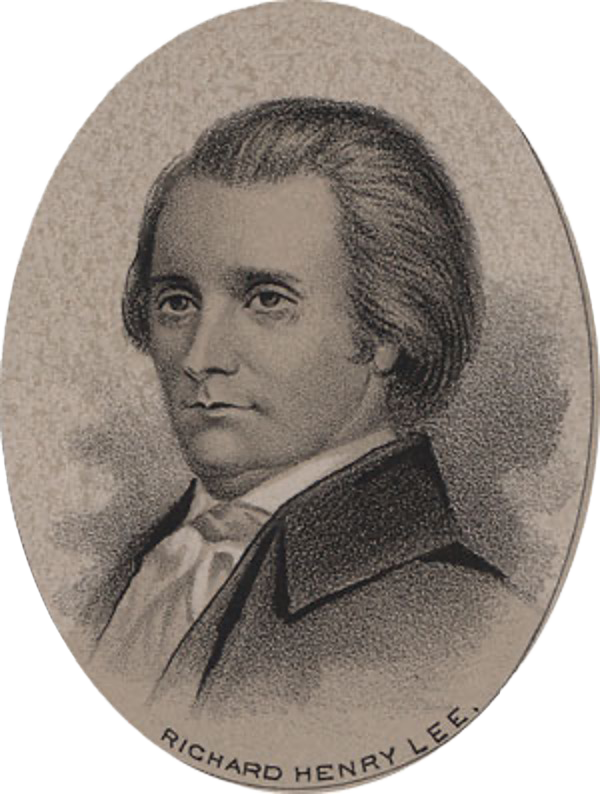

A third major Antifederalist out-of-doors writer alluded to above was The Federal Farmer. He is presumed to be Richard Henry Lee, although this authorship has been challenged. He wrote five original letters in October 1787 in which he argued 1) that the proposed plan would lead to consolidation of the States under one government and that 2) the powers of the general government were ill defined. He devoted a number of additional letters to representation in the legislative branch and the need for a Bill of Rights.

“Out-of-Doors” Debate Materials

An Essay-by-Essay Summary of The Federalist including a paragraph by paragraph summary of the leading essays. Includes direct links to each of the 85 essays.