Major Themes in the Adoption of the Bill of Rights

We have included coverage of six major themes of the Bill of Rights in response to requests from teachers and users of our site for a focused coverage of issues that they have deemed worthy of such emphasis.

Father James and the Levy Thesis

An important question is why would James Madison, “the Father of the Constitution” become, in the words of Leonard Levy, “the Father of the Bill of Rights?” Recall that Madison was the author of the Vices of the American system as well as the Virginia Plan and Federalist 10. None of these Pro-Constitutional documents call for a bill of rights.

The most obvious answer to why Madison would be the father of both the Constitution and the Bill of Rights is “politics.” Over the last 75 years, the word “politics” in historiography has been associated with “self interest,” and possibly “unprincipled,” and contradictory conduct. And when it comes to Madison’s conduct, historians have a gold mine of possible contradictory conducts to explore, the most famous of which is why the author of The Federalist of 1787 is also the author of the Virginia Resolutions of 1798? But we have the same question here at the very founding itself: hasn’t Madison contradicted himself in becoming the father of the Bill of Rights when just a year earlier he declared that a bill of rights was unnecessary and improper? This idea of a contradictory Madison is reinforced by contemporary constitutional scholarship that emphasizes that the Amended Constitution is different from and supersedes the original Constitution. It doesn’t help that Madison referred in letters to his friends that the project to secure the Bill of Rights was “nauseous” and “wearisome.”

The low-ground answer to the question of why Madison took the lead on promoting a bill of rights in the House essentially rejects statesmanship as an explanation for Madison’s leadership. Madison’s position, according to this view, is based in the lower motives of narrow self-interest, especially political survival. Once again, Levy is a good representative of this interpretation. Denied the opportunity to become Senator Madison, House candidate Madison promised to take the lead on a bill of rights in order to defeat his opponent Monroe a Limitation Antifederalist in a district drawn in his favor in a closely held House election. The strategy was successful: he defeated Monroe by a vote of 1308-972. Madison was simply delivering on his electoral promise as a practical politician.

And some of Madison’s allies in the First Congress seem to confirm Levy’s thesis. Senator Robert Morris writes the following to Francis Hopkinson on August 15, 1789: “The House of Representatives are now playing with Amendments, but if they make one truly so I’ll hang. Poor Madison got so cursedly frightened in Virginia, that I believe he has dreamed of amendments ever since. This however is, ad Captandum [to play the crowd].”

Representative Abraham Baldwin wrote to Joel Barlow on June 14, 1789: “A few days since, Madison brought before us propositions of amendment agreeably to his promise to his constituents. Such as he supposed would tranquillize the minds of honest opposers without injuring the system. We are too busy at present in cutting away at the whole cloth, to stop to do any body’s patching. There is no such thing as antifederalism heard of. Rhode Island and North Carolina had local reasons for their conduct, and will come right before long.”

We have emphasized earlier that 1) the actual ratification of the Constitution, 2) Madison’s quest for a unanimous ratification, 3) and the exchange between Madison and Jefferson about a bill of rights, both before and after the ratification of the Constitution, were critically important to Madison’s statesmanship in the First Congress.

And part of that statesmanship was to 4) moderate the strong Federalists to see the importance of taking the lead on behalf of a bill of rights. Edmund Randolph writes to Madison as early as June 30, 1789 that his strategy seems to be working: “The amendments, proposed by you, are much approved by the strong foederalists here and at the Metropolis [Richmond]; being considered as an anodyne to the discontented.”

His strategy was also to separate the more dogmatic Antifederalist leaders like Mason, Gerry, Henry, and the two Senators from Virginia from the rank and file Limitation Antifederalists. In the process 5) he provided the context for North Carolina and Rhode Island to join the union. Fellow Constitutional Convention delegate William R. Davie wrote to James Madison on June 10, 1789 that this strategy also seemed to be working:

You are well acquainted with the political situation of this State [North Carolina], its unhappy attachment to paper money, and that wild skepticism which has prevailed in it since the publication of the Constitution. It has been the uniform cant of the enemies of the Government, that Congress would never propose an amendment themselves, or consent to an alteration that would in any manner diminish their powers. The people whose fears had been already alarmed, have received this opinion as fact, and become confirmed in their opposition; your notification however of the 4th. of May has dispersed almost universal pleasure, we hold it up as a refutation of the gloomy prophecies of the leaders of the opposition, and the honest part of our antifederalists have publicly expressed great satisfaction on this event.

That is the high ground defense of Madison’s persistent prudence. This prudence comes through in his June 8, 1789 speech where he distinguishes between rejecting hostile amendments and supporting a friendly bill of rights incorporated within the body of the Constitution itself. And the persistence is shown by his determination to practically “will” a bill or rights into completion by the end of the First Session. And Madison’s actions show that he interpreted “the republican principle” at its deepest level to be what he called in The Federalist “the deliberate sense of the community.” The “American Mind” was Jefferson’s expression for Madison’s “Sense of America.”

The Magna Carta and the Bill of Rights

There is a widespread opinion on both sides of the Atlantic that as the Magna Carta is to the British attachment to rights, the American version of this attachment is to be found in the U.S. Bill of Rights. Sometimes we hear more: that not only the origin, but also the substance of the U.S. version, is to be found in the Magna Carta.

To be sure, we have to start the rights narrative somewhere and since participants in the rights debate over 400 years don’t seem inclined to go further back than the Magna Carta, it seems reasonable to start there. And despite the feudal language and medieval concerns that run through, and thus date, the document, there is something enduring there that appeals to subsequent generations.

We suggest that the enduring quality is an appeal through the centuries that those who govern us do so in a reasonable manner. And all the better to secure the proposition that rulers exercise their power in a reasonable manner, we write down what we think is unreasonable conduct. Thus a list of what those in authority can’t do emerges.

In particular, we might say that the Magna Carta calls for the rule of law in opposition to the rule of unreasonable men. Furthermore, the rule of law is to be secured by an attachment to the due process of law.

The question then is how much of the Magna Carta made its way into the U. S. Bill of Rights? The answer is 9 of the 26 provisions in the Bill of Rights can be traced back to the Magna Carta. That’s about a third or 33%. And these provisions are heavily concerned with the right to petition and the due process of law.

The Magna Carta does not call for an abolition of the monarchy or a change in the feudal order. Nor does it call for religious freedom or freedom of the press. The U.S. Bill of Rights, however, presupposes the abolition of monarchy and feudalism; the American appeal to natural rights raises the question of religious freedom and freedom of the press.

So, we have two influences on the U.S. Bill of Rights: 1) the Magna Carta due process tradition that is incorporated in a third of the Bill of Rights and 2) the American home grown tradition of natural rights that is incorporated in two-thirds of the Bill of Rights.

The Constitutional Framers and the Bill of Rights

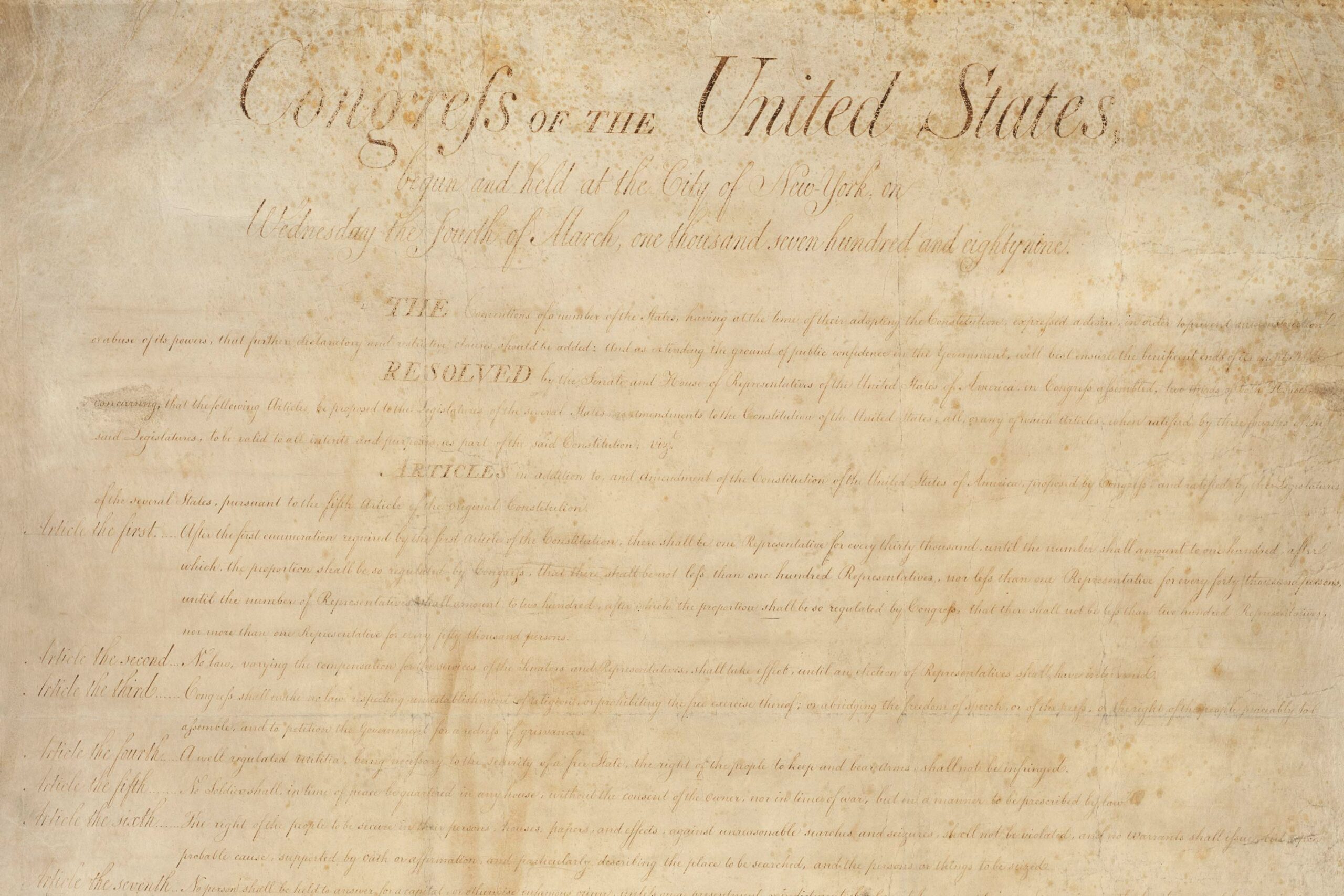

The First Federal Congress, also known as the 1st Congress of the United States, met in three sessions between March 4, 1789 and March 3, 1791. The first two sessions were held in New York and the final session in Philadelphia. Our interest is in the First Session of the First Congress: March 4, 1789 - September 29, 1789.

It is fascinating that Representatives James Madison, Roger Sherman, Elbridge Gerry, Nicholas Gilman, Thomas Fitzsimmons, George Clymer, Daniel Carroll, Abraham Baldwin, Hugh Williamson, and Senators Richard Bassett, Pierce Butler, Oliver Ellsworth, W. S. Johnson, George Few, Rufus King, Robert Morris, John Langdon, William Patterson, George Read, and Caleb Strong were all members of the First Congress. So there were 9/59 Framers in the House eight signers and one non-signer Gerry and 11/22 Framers in the Senate ten signers plus one non-signer, but supporter, Ellsworth. Although several Constitutional Framers, Robert Morris in particular, seemed irritated that Madison insisted that the First Congress send amendments to the Constitution to the States for ratification by the end of the First Session, Gerry alone opposed Madison and he did so to the very end. We should add that President George Washington gave his support for Madison’s plan of action in his First Inaugural Address, and George Mason, although not a member of the First Congress was a serious behind-the-scenes obstacle to Madison’s efforts to secure a bill of rights. As usual, Edmund Randolph was unpredictable, this time in the Virginia State Legislature.

At the Constitutional Convention, in mid-September, 1789, Mason and Gerry failed to persuade any of their fellow delegates to preface the Constitution with a bill of rights. “It would give great quiet to the people,” urged Mason. He also thought it would be easy to compile a list given the widespread presence of a prefatory bill of rights at the state level. A few days later, on September 17, 1787, they declined to sign the Constitution citing the absence of a bill of rights among their reasons. Mason’s lead objection read thus: “There is no Declaration of Rights, and the laws of the general government being paramount to the laws and constitution of the several States, the Declaration of Rights in the separate States are no security. Nor are the people secured even in the enjoyment of the benefit of common law.”

Madison recognized what he called Mason’s “ill-humor” in a October 24, 1787 letter to Thomas Jefferson: “Col. Mason left Philadelphia in an exceeding ill humor indeed. A number of little circumstances arising in part from the impatience which prevailed towards the close of the business, conspired to whet his acrimony. He returned to Virginia with a fixed disposition to prevent the adoption of the plan if possible. He considers the want of a bill of rights as a fatal objection.”

In the First Congress, Gerry became more and more a determined Structural Antifederalist and dug in to alter the structure and powers of the new government rather than act as a Limited Antifederalist and try to limit its reach by a bill of rights! And also interesting is that Madison and Sherman, who feuded at the Constitutional Convention over the merits of the Connecticut Compromise, renewed their feud over the Bill of Rights in the First Congress!

It is also worthy of note that the close electoral numbers in the ratifying debates see the closeness of the ratification votes in Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Virginia, and New York and the sense of tension and urgency brought about by the close distribution of the ratification votes were absent in the First Congress. There were only 13/59 Antifederalists (four from Virginia) elected to the House and 2/22 (both from Virginia) selected to the Senate.

But there was one very persistent Madison who understood the numbers. Constitutional Framer Hugh Williamson understood the ramifications of the actions of the First Congress. Writing to Madison on July 2, 1789, Williamson remarked: “I verily believe that unless you can persuade Congress seriously to take up & agree to some such Amendments as you have proposed, North Carolina will not confederate.”

To: Samuel Johnson

From: J. Madison

June 21, 1789

“In the inclosed paper is a copy of a late proposition in Congress on the subject of amending the Constitution.”

This poor Antifederalist Congressional electoral performance is surprising because, as Charlene Bickford has pointed out, “Amendments became the only national issue during the election.” We hazard the following interpretation of the 1789 election. The American voter generally had lost the appetite for amendments that would change the structure and power of the government. Whatever appetite remained for such radical change was concentrated mainly in Massachusetts and Virginia. To the extent that these Antifederalists remained adamant in their rejection of the work of the Philadelphia Convention, the more they would be isolated from “the great difficulty” of governing the nation. To be sure, the specter of a Second Convention still haunted the debate, Mason, Henry, Gerry, and Tucker did their best to convulse the process, but Madison prevailed on the First Congress to adopt friendly alterations to the original Constitution.

The Structural Antifederalists, as distinguished from what we shall call Limitation Antifederalists, were unwilling to settle for what Madison himself a Prudential Federalist had dismissed during the ratifying campaign as mere “parchment barriers.” They wanted more than a bill of rights. They wanted a radical return to the Articles of Confederation. And interestingly, what we shall call the Determined Federalists actually agreed with the Structural Antifederalists: what Madison was about to propose to the First Congress concerning a bill of rights was a waste of time, “milk and water” proposals.

The Determined Federalists such as Butler, Langdon, and Morris wanted to get on with the business of setting up the Cabinet Departments, writing a Judiciary Act and, in the third session, creating a national bank. Madison, according to both the Structural Antifederalists and the Determined Federalists, was offering “a tub to the whale.”

The House appointed Madison, Sherman, and Vining to the Conference Committee. The Senate appointed Ellsworth, Carroll, and Patterson to the Conference Committee. So 4/6 members of the Conference Committee were Framers in Philadelphia. They agreed on 12 amendments that they considered to be consistent with the original Constitution they framed.

James Madison wrote to Edmund Pendleton on April 9, 1789: “ The subject of amendments has not yet been touched. From appearances there will be no great difficulty in obtaining reasonable ones. It will depend however entirely on the temper of the Federalists, who predominate as much in both branches, as could be wished.”

William Davie wrote to James Madison on June 10, 1789: “ You are well acquainted with the political situation of this State, its unhappy attachment to paper money, and that wild skepticism which has prevailed in it since the publication of the Constitution. It has been the uniform cant of the enemies of the Government, that Congress would exert all their influence to prevent the calling of a convention, and would never propose an amendment themselves, or consent to an alteration, that would in any manner diminish their powers.”

George Clymer wrote to Richard Peters on June 8, 1789: “Madison this morning is to make an essay towards amendments but whether he means merely a tub to the whale, or declarations about the press liberty of conscience &c. or will suffer himself to be so far frightened with the antifederalism of his own state as to attempt to lop off essentials I do not know I hope however we shall be strong enough to postpone. Afternoon Madison’s has proved a tub on a number of Amendments. But Gerry is not content with them alone, and proposes to treat us with all the amendments of all the antifederalists in America.”

Did Madison Flip-Flop?

Two critical compromises were made during the in-door debates over the ratification of the Constitution. The first was the Massachusetts Compromise where ten Antifederalists agreed to ratify the Constitution now in exchange for what we might call a gentleman’s agreement that Massachusetts Congressmen in the First Congress would pursue the adoption of nine amendments to the Constitution. This agreement ratify now and amend later effectively took the immediate steam out of two Antifederalist strategies: 1) to place conditional amendments on the Constitution before ratification and 2) to call for a Second Convention to reconsider the work of the Philadelphia Convention. Although the Massachusetts ratification compromise was unconditional, the compromise thrust the issue of amendments to the forefront of the ratification discussion in the remaining states of Maryland, South Carolina, North Carolina, New Hampshire, Virginia, New York, and Rhode Island.

It is beyond the scope of this commentary to detail what took place at these ratifying conventions concerning conditional amendments. Suffice it to note here that the Massachusetts Compromise amendments called for a fundamental change in the structure and powers of the new federal government and paid only limited attention to a bill of rights. By the time Virginia and New York met, however, a new compromise had emerged: ratify now and a bill of rights later. Both of these states repeated the Massachusetts theme of ratify now and amend later, an approach also adopted by New Hampshire, but the theme of a bill of rights was added that was distinguished from the call for amendments to change the structure and powers of the new government. The closest that conditional amendments came to passage was in New York.

We know what George Mason thought about “ratify now and amend later.” In a letter to Jefferson dated May 26, 1788, concerning the upcoming Virginia Ratifying Convention in June, he said: “There seems to be a great majority for Amendments; but many are for ratifying it first, and amending afterwards. This idea appears so utterly absurd, that I cannot think any Man of Sense candid, in proposing it.” This comment was made before the Virginia Ratifying Convention made the distinction between amendments and a bill of rights, thus introducing the new Virginia formula: ratifying it first, and a bill of rights afterwards.

That’s when, for Mason, the absurd turned into a farce. Writing to John Mason on July 31, 1789, after Madison introduced his 39 Proposals on June 8 and the Select Committee had moved them on to the next stage, he says:

You were mistaken in your suggestion, that the Publication you saw of Mr. Madison’s, was a certain indication of proper Amendments to the Government being obtained. It was indeed, natural enough to think so. But the Fact was, Mr. Madison knew that he could not be elected, without making some such Promises. By them he carried his election; and in order to appear as good as his word, he has made some motions in Congress on the subject; and to carry on the farce, is now the ostensible Patron of Amendments. Perhaps some Milk & Water Propositions may be made by Congress to the State Legislatures by way of throwing out a Tub to the Whale; but of important & substantial Amendments, I have not the least Hope.

Mason’s response to both the absurd and the farcical then was to join forces with other Virginia Antifederalists like Patrick Henry and call for a Second Constitutional Convention whose members would reject the work of the Philadelphia Convention. And, as a second strategy, they would try to make sure that Virginia select Antifederalists to the First Congress where they would support the amendment proposals of the Virginia Ratifying Convention rather than the bill of rights proposals that Madison was befriending. So these Virginia Antifederalists took the absurd story to the farce level one step further. Their position was Second Convention now, or amend now.

A second convention was something that Madison vigorously opposed. Writing to George Lee Turberville on November 2, 1788, Madison expressed his opposition to 1) the imprudence of a Second Convention, 2) the “misinformation” spread by Patrick Henry that Madison thought that “not a letter of the Constitution could be spared,” and 3) the negative effect which such a Convention would have on the freedom movement in France. Also note Madison’s appeal to “the apparent sense of America” in his support for a bill of rights being passed by the First Congress. Earlier in Federalist 63 he expressed his understanding of “the republican principle” in the expression “the deliberate sense of the community”:

You wish to know my sentiments on the project of another general Convention as suggested by New York. I shall give them to you with great frankness, though I am aware they may not coincide with those in fashion at Richmond or even with your own. I am not of the number if there be any such, who think the Constitution, lately adopted, a faultless work. On the contrary there are amendments which I wished it to have received before it issued from the place in which it was formed. These amendments I still think ought to be made according to the apparent sense of America and some of them at least I presume will be made .

Having witnessed the difficulties and dangers experienced by the first Convention which assembled under every propitious circumstance, I should tremble for the result of a Second, meeting in the present temper of America and under all the disadvantages I have mentioned .

The Constitution just established has filled that quarter of the Globe (Europe) with equal wonder and veneration, that its influence is already secretly but powerfully working in favor of liberty in France.

Madison repeats his claim that he is not opposed to friendly alterations in the Constitution in a letter to George Eve on January 2, 1789. In the process, he indicates that a “change of circumstances” the ratification of the Constitution permits the First Congress perhaps we might add in Madisonian language, that “the sense of America” wants the First Congress to propose “the most satisfactory provisions for all essential rights”:

I freely own that I have never seen in the Constitution as it now stands those serious dangers which have alarmed many respectable Citizens. Accordingly whilst it remained unratified, and it was necessary to unite the States in some one plan, I opposed all previous alterations as calculated to throw the States into dangerous contentions and to furnish the secret enemies of the Union with an opportunity of promoting its dissolution.

Circumstances are now changed: The Constitution is established on the ratification of eleven States and a very great majority of the people of America; and amendments, if pursued with proper moderation and in a proper mode, will be not only safe, but may serve the double purpose of satisfying the minds of well meaning opponents, and of providing additional guards in favor of liberty. Under this change of circumstances, it is my sincere opinion that the Constitution ought to be revised, and that the First Congress meeting under it, ought to prepare and recommend to the States for ratification, the most satisfactory provisions for all essential rights, particularly the rights of Conscience in the fullest latitude, the freedom of the press, trials by jury, security against general warrants &c. I think it will be proper also to provide expressly in the Constitution, for the periodical increase of the number of Representatives until the amount shall be entirely satisfactory; and to put the judiciary department into such a form as will render vexatious appeals impossible .

He repeats “the change of situation” theme to Thomas Mann Randolph in a letter dated January 13, 1789:

The change of situation produced by the establishment of the Constitution, leaves me in common with other friends of the Constitution, free, and consistent in espousing such a revisal of it, as will either make it better in itself; or without making it worse, will make it appear better to those, who now dislike it.

It is accordingly, my sincere opinion, and wish, that in order to effect these purposes, the Congress, which is to meet in March, should undertake the salutary work. It is particularly, my opinion, that the clearest, and strongest provision ought to be made, for all those essential rights, which have been thought in danger, such as the rights of conscience, the freedom of the press, trials by jury, exemption from general warrants, &c.

I think also, that the periodical increase of the House of Representatives, until it attains a certain number, ought to be expressly provided for, instead of being left to the discretion of the government. There is room likewise in the Judiciary department for amendment. It ought to be so regulated, as to render vexatious, and superfluous appeals, impossible. In a number of other particulars, alterations are eligible either on their own account, or on account of those, who wish for them.

What Jefferson said to Mason in a letter dated June 13, 1790, Madison might well say to us: “In general I think it necessary to give as well as take in a government like ours.”

The Two Religion Clauses

How did the two religion clauses “Congress shall make no law (A) respecting an establishment of religion, or (B) prohibiting the free exercise thereof” make their way into the First Amendment of the Constitution? Put differently, what happened to Madison’s original three-pronged religion proposals? There are five dimensions to the development of the religion clauses in the First Congress.

- June 8 Speech. James Madison proposed three religion clauses in his June 8 speech in the First Congress. He proposed that the Constitution be opened up and three clauses inserted in Article I, Section 9, “1) The civil rights of none shall be abridged on account of religious belief or worship, 2) nor shall any national religion be established, 3) nor shall the full and equal rights of conscience be in any manner, or on any pretext, infringed.”

- The House Select Committee. On July 28, the House Select Committee combined Madison’s proposals 2) and 3) to read: “No religion shall be established by law, nor shall the equal rights of conscience be infringed.” Thus the phrase “national religion” was removed. The rights of conscience clause remained the same.

- Full House Debates and Decisions.The House revisited the religion clauses on three separate occasions during their consideration of the House Select Committee Report during the final two weeks of August.On August 15, the House adopted the following: “The Congress shall make no laws touching religion or infringing the rights of conscience.” The important points to note here are a) the full House substituted “no laws touching religion” for “no religion shall be established by law,” and b) Madison withdrew a motion to reinsert “national religion” into the combined clauses.The religion clauses were further altered in the House on August 20 to read: “Congress shall make no law establishing religion or to prevent the free exercise thereof or to infringe the rights of conscience.” Note that “no law establishing religion” from the Select Committee was reintroduced and accepted five days after initial rejection into the religion clauses. Also “the free exercise” clause made its inaugural appearance during these August debates of the whole House and was placed along side the “rights of conscience clause.” The free exercise clause, at least on August 20, was not intended to replace the rights of conscience clause.The final House version that was sent to the Senate on August 24 substituted “prohibiting” for “to prevent,” in the phrase concerning “the free exercise” of religion.To summarize, the House took Madison’s three-pronged proposal on the religion question, and sent the following to the Senate as Amendment Three of the Constitution: “Congress shall make no law I) establishing religion or II) prohibiting the free exercise thereof or III) to infringe the rights of conscience.” So we are back to three dimensions of the religion clauses once again.Four points should be noted about the three part House version that went to the Senate. First, the House rejected Madison’s proposal to insert the religion clauses into Article I, Section 9 of the Constitution. Instead, the three religion clauses became House Amendment Article III. Second, “the civil rights of none shall be abridged on account of religious belief or worship” clause has become the “free exercise” clause. Third, “the rights of conscience” clause has emerged unscathed from June 8 through August 24. Fourth, the “nor shall any national religion be established,” clause is replaced by “Congress shall make no law establishing religion.”

- The Senate.The Senate considered the three religion clauses of House Amendment Article III on several occasions between September 3 and September 9. Two days are important for helping us to answer our opening question.On September 3, at least six different configurations of the religion clauses were rejected. In the end, the Senate adopted the first two parts of House Amendment Article III but dropped “nor shall the rights of conscience be infringed.” So we are back to two religion clauses again. More importantly, what was so vital a part of Madison’s 39 Proposals the right to conscience lost its way in the Senate. And the individual right of conscience never reappeared in the language of the religion clauses.On September 9, the Senate passed a motion to further amend House Amendment Article III to read as follows: “Congress shall make no law establishing articles of faith or a mode of worship, or prohibiting the free exercise of religion, or abridging the freedom of speech, or the press, or the right of the people peaceably to assemble and petition to the Government for the redress of grievances.” Two points are important here. The Senate continued to debate the wording of the establishment clause right to the very end and the religion clauses, for the first time, are bundled with what we today refer to as the expression and association clauses.

- The Conference Committee Report.The Conference Committee Report of September 24, 1789 shows that the House agreed with the Senate’s decision to bundle the religion clauses in exchange for a rewording of the religious establishment clause back in the direction of the House version. So we get: “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.”It was the Joint Conference Committee of three representatives and three Senators of which Madison was one of four Framers of the Constitution chosen right at the very end of the Congressional debates, that came up with the final formulation of the two religion clauses.

What about the Two Amendments and Three States that Got Away?

One of the unfortunate features about the ratification of the Bill of Rights is the widespread absence of documentary records from the state legislatures that made the decisions on whether or not to ratify these amendments proposed by the First Congress. There is virtually no detailed account of the debates that took place in the various state legislatures. But we know there must have been some debate because two amendment proposals were rejected. This silence is in contrast to the rather extensive documentation over the creation and ratification of the Constitution. See, for example, the multiple publication of what is now called Madison’s Notes of Debates as well as the nineteenth century work by Jonathan Elliott and the ongoing work since the 1980s by John Kaminski et al. There is sufficient, yet incomplete, coverage of the fate of Madison’s Bill of Rights proposals in the First Congress that were sent to the State Legislatures for ratification.

On October 2, 1789, President George Washington, at the request of the First Congress, sent the 12 amendments approved by the First Congress on September 25, 1789 to the executives of the 13 existing States. The President requested that the State Executives submit these 12 amendment proposals for adoption or rejection to their respective state legislatures. This Congressional request included sending the amendment proposals to Rhode Island and North Carolina even though they had not yet ratified the Constitution. On March 1, 1792, Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson announced that 10 amendments had been ratified by three-fourths of the state legislatures.

What happened in the intervening 29 months?

What we know is that Amendments Three through Twelve were adopted by the minimum 11/14 state legislatures necessary for adoption. Vermont had joined the union thus constitutionally changing the ratio to 11/14 from 10/13. Interestingly, however, Jefferson did not include Vermont in his official count. The Jefferson table suggests that he considered the ratification by 10 of the original 13 states to be the standard for adoption of the Bill of Rights. It turns out that 11/14, and 10/13, states supported Amendments Three through Twelve.

We also know that the First and Second Amendments of the original 12 amendments were not officially ratified. Nine of fourteen states voted in favor of the original First Amendment: Delaware and Pennsylvania voted “no.” Two more votes were needed for passage if we follow the 11/14 requirement. Eight of fourteen approved the original Second Amendment: New Hampshire, New Jersey, and New York voted “no.” Three more votes were needed for passage if we follow the 11/ 14 requirement. Although Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Georgia were not needed for the passage of Amendments Three through Twelve, could their vote have made a difference in the passage of the original First and Second Amendments? Yes, but we need to be cautious in coming to conclusions. Jefferson, Washington, and the Second Congress in 1791 never received any official notification that Massachusetts, Connecticut, or Georgia may have, or may not have, ratified any or all of the proposed Bill of Rights. But what ever did or did not happen in these three states did not prevent Jefferson from announcing the passage of Amendments Three through Twelve which then became officially the First Ten Amendments to the Constitution. When the Second Congress adjourned, the ratification of 10 Amendments by 11 States had been officially received by Jefferson, the Congress, and the President. The Constitution now contained a Bill of Rights.

Three States did not officially support the adoption or rejection of the Bill of Rights. This absence of official adoption or rejection in the 1790s was symbolically rectified in 1939 when the legislatures of Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Georgia ratified the Bill of Rights on the 150th anniversary of the Congressional signing in September 1789.

So what are we to make of these three states that apparently did not, officially at least, adopt the Bill of Rights between 1789-1791? Most importantly, would their official participation have made a difference to the possible passage of the original First and Second Amendments? What if we were able to recover reliable records that showed that these three state legislatures did meet and did pass most, if not all, of the original 12 Amendment proposals? Would this new information require a correction to the constitutional record?

For the original First Amendment—what we shall call “the Representation Amendment”—to be part of the Bill of Rights would have required two of the following three states to agree: Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Georgia. There is no existing evidence about what happened in Georgia. So everything depends on what we can find out about Massachusetts and Connecticut. For the original Second Amendment—what we shall call “the Congressional Pay Amendment”—to be part of the Bill of Rights would have required one of the following three states to agree: Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Georgia. There is no existing evidence about what happened in Georgia. So, again, everything depends on what we can find out about Massachusetts and Connecticut.

Bernard Schwartz in Volume Five of his Roots of the Bill of Rights (1971) indicates that both branches of the Massachusetts legislature in February 1790, after a couple of weeks of debate, approved nine of the twelve amendments proposed by Congress. They did not ratify the original First, Second, and Twelfth Amendments. This is confirmed in a report that appeared in the Providence Gazette and Country Journal dated February 13, 1790. But even though both branches supported nine amendments, this decision was not officially reported to the Secretary of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Jefferson wrote to Christopher Gore on August 8, 1791 to inquire about the 18-month-delayed status of the Bill of Rights in Massachusetts. Gore responded to Jefferson on August 18, 1791: “it does not appear that the (Conference) Committee ever reported any bill.” And their decision would not have changed the outcome of the original Congressional proposals.

According to Eugene Martin LaVergne, both branches of the Connecticut Legislature in 1790 actually ratified all 12 amendments. But the ratification document was misfiled in a 1780 rather than a 1790 folder and never reached Jefferson and the Congress. See Eugene M. LaVergene v. Rebecca Blank, Acting Secretary of Commerce, et al. No. 12-778. The main point of this discovery, however, is not primarily to correct the historical record but to correct the constitutional record. As I understand the claim, the “documentary find” means that all 12 amendments need to be included in the Constitution and not just Three through Twelve. The concern seems to be particularly focused on the original First Amendment.

There is no doubt that Connecticut’s role in the Constitutional record has been insufficiently recognized. But the restoration of that vital role is not enhanced by the discovery of a misfiled document. It would have required not only Connecticut to vote in favor of the First Amendment, but also either Massachusetts or Georgia. We know that Massachusetts voted against the First Amendment and we have no idea how Georgia voted. But even if we learn someday that Georgia voted in favor of the First Amendment, there is no need to revise the Constitutional record. The original First Amendment was intended to be effective until a certain number of representatives had been achieved. After that it was up to Congress to set the limit. And Congress followed the proportionality approach until roughly 100 hundred years ago. Then they set the limit at 435. But that can be changed by Congressional action rather than a battle over the Constitution. As far as the original Second Amendment is concerned, that is now the 27th Amendment ratified by three-fourths of the states on May 7, 1992.