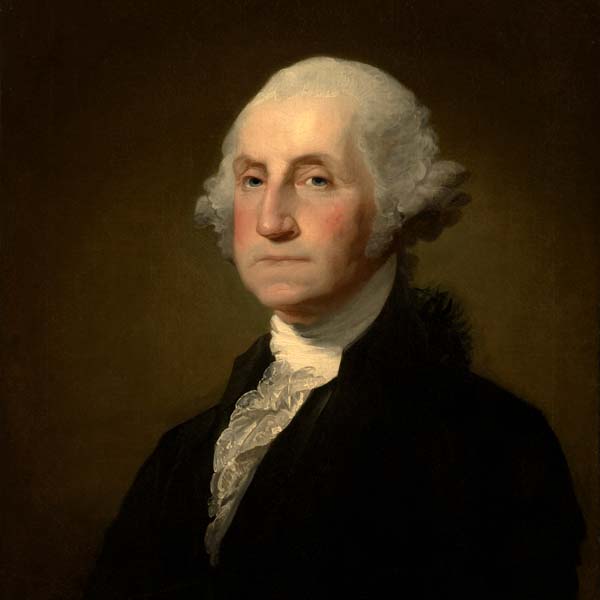

Washington as Statesman at the Constitutional Convention by Junius Brutus Stearns

Junius Brutus Stearns was born, Lucius Sawyer Stearns, in Arlington, (The New York Times says it was Burlington) Vermont in 1810. Stearns died in Brooklyn, New York in 1885 at the age of 75. The New York Times, September 19, 1885, reported that he died as result of a head-on carriage accident. “Mr. Stearns was thrown violently upon the pavement, and his skull was fractured.” Raphael Stearns, who is sometimes identified, erroneously, as Junius Brutus Stearns, was in fact his son. (We wish to thank Lauren Lessing at the Colby College of Art for bringing this error to our attention.) He was a pupil at, and a member of the Council of the National Academy of Design in New York and a member of the Academy for several decades, including being the recording secretary from 1851 to 1865. Stearns is best known for his five part “Washington Series,” 1847-1856, in which he chronicles George Washington‘s life as farmer at his plantation; citizen at his wedding; soldier at Monongahela; Christian on his deathbed, and statesman at the Founding.

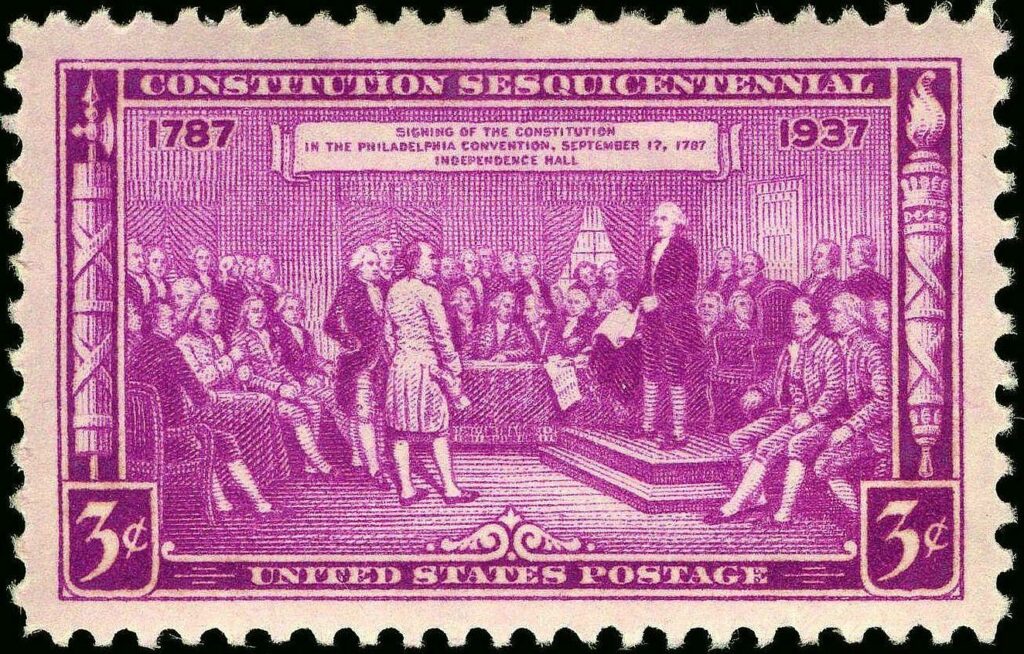

“The Statesmanship of Washington,” a three feet by four and a half feet oil on canvas, is the fifth and final painting in the series that includes “Washington and the Indians” (1847), “The Marriage of Washington” (1849) and “Farmer at Mount Vernon” (1851). Stearns’s “Statesman” painting was actually reproduced on a three-cent commemorative postage stamp in September 1937, first issued in Philadelphia on the 17th of September, to honor the 150th anniversary of the Signing of the Constitution!

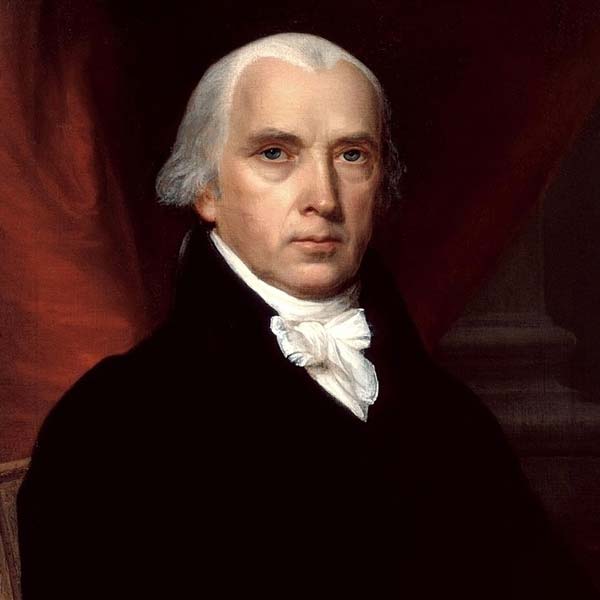

We suggest we view the Stearns “Statesmanship” painting as the nineteenth century version of the famous Christy “Signing” painting of the twentieth century which also had the 150th anniversary in mind. What is remarkable is that the Stearns painting is the first to portray the activities of the Constitutional Convention. This is in contrast to the Trumball painting of the Declaration of Independence and individual portraits of the Founders that were readily known and accessible. The first known depiction of the Convention is an engraving by Elkanah Tisdale in 1823. In “Statesmanship,” Stearns portrays 39 delegates in attendance at the Convention. Thirty-eight are indeed the number of delegates actually in attendance on September 17, the day of the Signing of the Constitution. Although 38 delegates physically “signed” the Constitution, George Read of Delaware signed John Dickinson‘s name. Dickinson was indisposed. (Christy parks Dickinson in the upper right portion of his painting. Christy actually paints 40 people; he displays the Secretary of the Convention, William Jackson, prominently.) In support of this interpretation that Stearns’s painting can be viewed as a pre-Christy version of the Signing, take a look at the curtains. One set are closed and one set are open indicating the movement from a deliberation in secret for over four months to a decision in the light of day. Christy has both curtains open indicating that the signing has occurred. Stearns, like Christy, also has one delegation sitting around a table — in fact both painters have one, and only one, delegation sitting at a table — and Stearns seems to portray a plan falling to the floor in contrast to the one Washington is presenting to the delegates for signing. Thus, I think it not unreasonable to presume that the frustrated folks sitting at the table for both Stearns and Christy are Roger Sherman and William Johnson from the Connecticut delegation. (Christy shows crumpled paper on the floor.) What’s with the tiny black slippers for the delegates, but real shoes for the General? Also important, as a pre-Christy rendition, is the prominence of Washington in the painting, taller than anyone else, raised above everyone else, clearly more identifiable than anyone else, and more illuminated than anyone else and “in charge.” Christy similarly makes Washington prominent surrounded by the Rising Sun chair and all sorts of American flags to add to the celebrations. Unlike the Christy painting, however, where all the delegates can be identified, one has to work very hard to identify delegates other than Washington. He is truly an icon par excellence for Stearns. This Washington as icon remains through the Great Depression and the Second World War for many Americans. In fact, a majority of Americans had a commemorative symbol of Washington in their homes up through World War II. We suggest we divide the delegates into five groups and that might help us to identify the delegates and capture the intent of the artist. The first “group” is Washington who stands by himself. There is a second group of three standing in front of Washington. Who are these delegates? Behind these three, are thirteen delegates that make up the third group. Four are sitting in chairs and nine are standing behind them. Benjamin Franklin and James Madison are recognizable in the front row of the four delegates who are sitting. And all thirteen of this group look pretty satisfied and content with the outcome. Who are these other delegates? Between Washington and the “Second Group of Three,” and to the right of the General, are thirteen delegates divided into two subgroups: two or three are sitting around the table mentioned above, and the remainder standing and chatting. This “Fourth Group of Thirteen” does not look as content as the “Third Group of Thirteen.” Who are these delegates, and why do they seem a bit grim? There are nine delegates that are in the fifth and final group. They are all situated behind Washington. Who are these nine delegates? This is based on the version generously shared with me by The Virginia Museum of Fine Arts.