Symbolism of the Federal Pillars

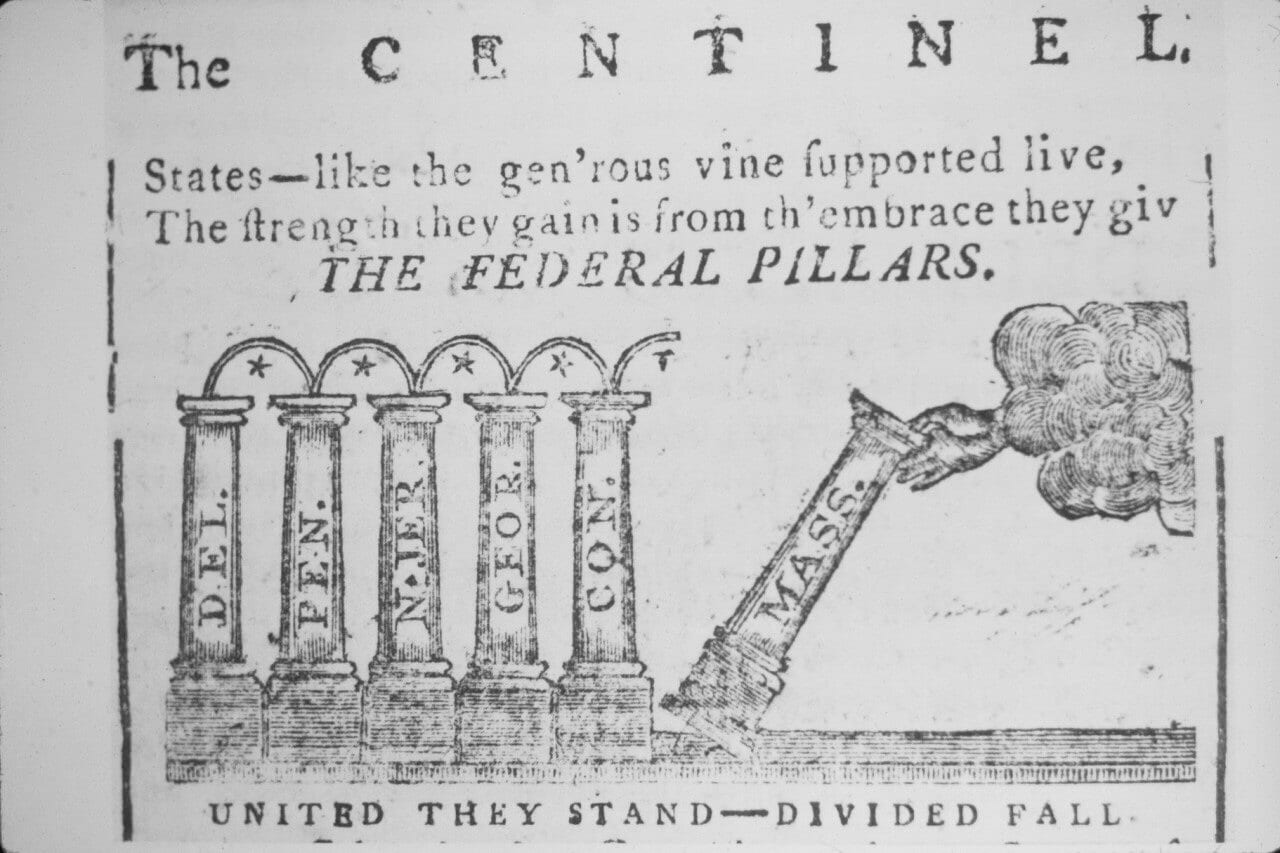

The political arithmetic of ratification outlined in Stage I of the Ratification story seemed to yield a mixed prognosis. On the one hand, only nine out of thirteen states were needed to ratify the Constitution. On the other hand, two New York delegates left the Constitutional Convention early; two delegates from Virginia refused to sign on September 17, as did one delegate from Massachusetts. The supporters of the Constitution began the ratification campaign in those states where there was little or no controversy, postponing until later the six more difficult states of Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Virginia, New York, North Carolina, and Rhode Island. Ben Kunkel has captured this challenge of the political arithmetic of ratification by anticipating the pillar narrative depicted in The Massachusetts Centinel.

As we saw in Stage II of the Ratification story, five pillars were quickly erected during the fall of 1787. But this fast start came to a halt in New England in the winter. Five states were united, but what about the remaining eight states? Would the outcome be divided? If so, then divided we might well fall.

In January 1788, the fate of the Constitution depended on what happened in Massachusetts. (And also initially on what happened in New Hampshire, but the ratification decision on the Constitution in that state was postponed until June.)

The Federal Pillars series was published in The Massachusetts Centinel over several months, but did not pick up the ratification story until the completion of Stage II and the start of Stage III. The pillars represent the order that the states, moving from left to right in the illustrations, ratified the Constitution. (The entire series is available from the Library of Congress.)

This is when—January 30, 1788, Stage III—The Massachusetts Centinel picks up the ratification story. The first two depictions from the newspaper below correspond to the end of Stage II and the start of Stage III. The February 9, 1788 edition announces the ratification of the Constitution in Massachusetts on February 7. The February 27 issue of The Centinel notes the postponement of ratification in New Hampshire on February 22 and the expectation that New Hampshire will yet rise. This marks the end of Stage III.

The word “pillar” had entered the phraseology of the ratification campaign. On February 15, 1788, James Madison wrote to George Washington. “I have at length the pleasure to enclose you the favorable result of the Convention at Boston. The amendments are a blemish, but are in the least Offensive form… The Convention of New Hampshire is now sitting. There seems to be no question that the issue there will add a seventh pillar, as the phrase now is, to the Federal Temple.” Note that Madison, like so many other close political observers, did not anticipate the imminent decision in New Hampshire to postpone their Convention until the summer.

Cyrus Griffin was far less optimistic about the fate of the “national fabric” upon receiving news of the New Hampshire postponement. In a letter dated March 24, 1788 he informed Madison: “The adjournment of New Hampshire, the small majority of Massachusetts, a certainty of rejection in Rhode Island, the formidable opposition in the state of New York, the convulsions and committee meetings in Pennsylvania, and above all the antipathy of Virginia to the system, operating together, I am apprehensive will prevent the noble fabric from being enacted.”

But the adoption of the Constitution in Massachusetts—the sixth pillar—actually spurred The Centinel to continue the raising of the pillars story into Stage IV: Springtime in the Middle States of Maryland and South Carolina. Entitled “Redunt Saturnia Regena,” the addition of the seventh and eighth pillars appeared in the June 11, 1788 issue of the newspaper.

And then came Stage V, the long hot summer of 1788. The Centinel kept readers informed across the continent with their continued coverage of the fate of the pillars. What would happen in New Hampshire, Virginia, and New York? Which state would be the ninth to ratify? The Centinel actually thought that Virginia, and not New Hampshire, would be the ninth state to ratify.

They ran another edition on August 2, 1788 showing that New Hampshire was the ninth state and also depicting the potential adoption of the Constitution in Virginia and New York. It also looks promising in the future for North Carolina, but the depiction of a split pillar in Rhode Island is not optimistic. With eleven pillars in place, The Centinel terminates its coverage of the fate of the pillars.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress. Reproduction Number: LC-USZ62-45591 (b&w film copy neg).

To extend the pillar narrative into Stage VI, however, we have a concluding illustration showing how the eventual ratification of the Constitution by North Carolina and Rhode Island might have been depicted in The Centinel. The heading to this artistic rendition United, We Stand-Divide, We Fall is inspired by the very first rendition of the pillar story in The Centinel and thus completes the account of the Six Stages of Ratification.

Courtesy of the Center for the Study of the American Constitution and John Kaminski. Professor Kaminski contracted with Paul Haas in 1990 to draw this final pillar rendition as part of the Rhode Island bicentennial celebrations. Professor Kaminski owns the original artwork and has graciously given permission to use it for our Pillar story.