Dimension I: Madison’s Proposals

Commentary

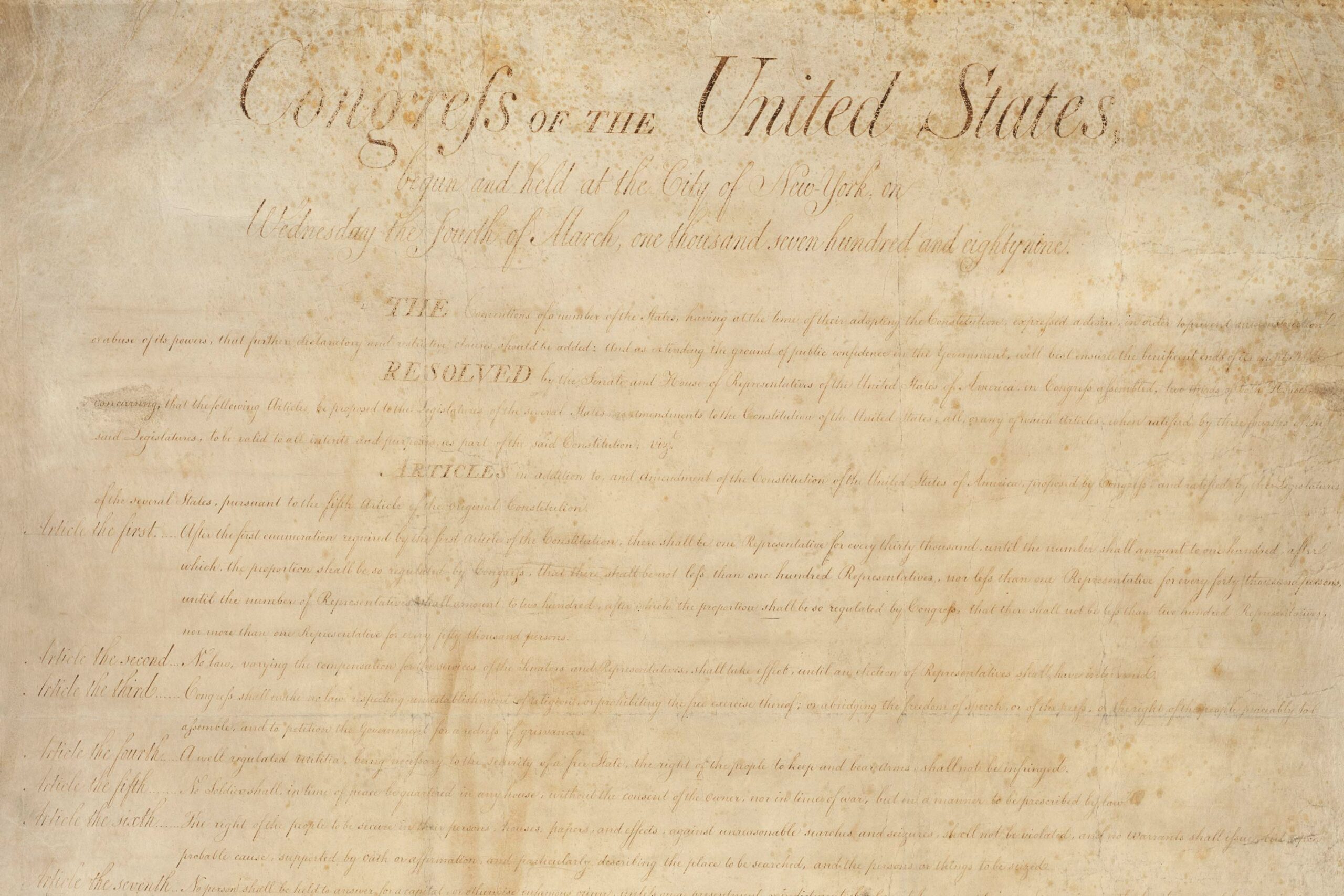

Here is a synopsis of Madison’s June 8 Proposals. 1) He starts with an attempt to integrate the Preamble to the Declaration into the Preamble of the Constitution thus confirming the American attachment to natural rights and then 2) moves to the 1:30,000 representation concern in Article I, Section 3 and then the conflict of interest over Congressional pay in Article I, Section 6 two Antifederalist criticisms that he admitted in The Federalist, especially 55-58, were important and then worked his way 3) through the remaining clauses of the original Constitution stopping along the way, especially at Article I, Section 9, to add restrains on the federal government including three “essential” restrains on the federal government dealing with the right of conscience, the freedom of the press, and jury trials, but also stopping 4) at Article I, Section 10 to add these three “essential” restraints on the state governments dealing with the right of conscience, the freedom of the press, and jury trials. He concludes 5) with three clarifications a) that because a right was not expressly listed didn’t mean the people did not retain that right an important Madison creation that emerged from his correspondence with Jefferson b) the Constitution confirms an attachment to the separation of powers doctrine and c) the powers not delegated to the federal government are retained by the states. Madison earlier acknowledged the centrality of b) and c) to the American project in Federalist 45 and 51.

In his notes for his June 8 speech in Congress, Madison describes a bill of rights as “useful but not essential.” In the process of outlining his notes, he actually shows why a bill of rights is probably essential as well useful. A bill of rights is essential because there is an essential difference between the new American Regime and the old British Empire: the right of conscience and the freedom of the press cannot be found, notes Madison, in the Magna Carta, the English Petition of Rights, or the English Bill of Rights. Whatever rights Englishmen have are the result of a “mere act of Parliament” and they are secured by frequent parliamentary elections. The rights of Englishmen are positive rights rather than natural rights. For Madison, there are three essential American rights: conscience, press, and jury. The first two are natural rights and the third is a positive right informed by natural rights. A bill of rights is also useful because it reminds us that liberty is secured by restraining the representatives of the majority who elect them at both the state and national level. It is true that Madison was more concerned with majority faction in The Federalist and thus did not consider a bill of rights to be either useful or essential.

The June 8 speech reflects his notion that the Founding was incomplete if a) two States, North Carolina and Rhode Island, were not part of the Union, b) people like Jefferson had reservations on behalf of the “sense of America” about endorsing the Constitution without a bill of rights, c) his own learning curve on the Antifederalist critique of the scheme of representation was not acted upon, d) the friends of the Constitution should demonstrate friendship toward reasonable amendments, and e) he was unable to drive a wedge between the Structural Antifederalists and the Limitation Antifederalists.

The 39 proposals included in his 9 Proposals in the June 8 speech were drawn heavily from the Virginia Ratifying Convention and, thus in turn, from the Virginia Declaration of Rights authored by George Mason! One would think that Mason would have been flattered, but he wasn’t. Madison’s proposals are merely “a tub to the whale,” groused Mason.

Madison’s own explanation for his support of a bill of rights is well summarized in his June 15, 1789 letter to Edmund Randolph: “The enclosed paper contains the proposition made on Monday last on the subject of amendments. It is limited to points which are important in the eyes of many and can be objectionable in those of none. The structure & stamina of the Government are as little touched as possible.”

Trench Coxe wrote to Madison on June 18, 1789 and identified three audiences who needed to be persuaded: 1) friends who thought a bill of rights to be a waste of time, 2) honest opponents who saw a bill of rights as essential to liberty, and 3) dishonest opponents who saw a bill of rights as a diversion from the main objective, namely, amendments that would fundamentally alter the structure and powers of the federal government. A bill of rights to the third group was a Tub to the Whale.

Coxe suggested the following impact on the three audiences: “[1]The most ardent & irritable among our friends are well pleased with them. On the part of the opposition, I do not observe any unfavorable animadversion. [2] Those who are honest are well pleased at the footing on which the press, liberty of conscience, original right & power, trial by jury etc. are rested. [3] Those who are not honest have hitherto been silent, for in truth they are stript of every rationale, and most of the popular arguments they have heretofore used. I will not detain you with further remarks, but feel very great satisfaction in being able to assure you generally that the proposed amendments will greatly tend to promote harmony among the late contending parties and a general confidence in the patriotism of Congress.”

Madison responded to Coxe on June 24, 1789 suggesting that “it is much to be wished that the discontented part of our fellow Citizens could be reconciled to the Government they have opposed, and by means as little as possible unacceptable to those who approve the Constitution in its present form. The amendments proposed in the House of Representatives had this twofold object in view.”

The position of the first group - the waste of time friends - is well articulated by Representative Fisher Ames. He wrote the following to Thomas Dwight on June 11, 1789: “Mr. Madison has introduced his long expected Amendments. They are the fruit of much labor and research. He has hunted up all the grievances and complaints of newspapers, all the articles of Conventions, and the small talk of their debates. It contains a Bill of Rights . Upon the whole, it may do good towards quieting men who attend to sounds only, and may get the mover some popularity which he wishes.” And to George R. Minot on June 12, 1789, Ames considered Madison’s proposals “a prodigious great dose for a medicine. But it will stimulate the stomach as little as hasty pudding. It is rather food than physic. An immense mass of sweet and other herbs and roots for a diet drink.”

The second group is best represented by Jefferson in his exchanges with Madison.

And the third group is best represented by George Mason. In a letter to John Mason dated July 31, 1789, Mason articulated the tub to the whale position: “You were mistaken in your Suggestion, that the Publication you saw of Mr. Madison’s, was a certain Indication of proper Amendments to the Government being obtained. Perhaps some Milk & Water Propositions may be made by Congress to the State Legislatures by Way of throwing out a Tub to the Whale; but of important & substantial Amendments, I have not the least Hope.”